Convergence and divergence: China-Russia relations in the age of Trump

Executive summary

- The Sino-Russian partnership is based on cold-blooded strategic calculus, shaped by convergent interests in security, geopolitics, and economic cooperation.

- For both sides, the relationship is of central importance. Yet it is not an alliance, but a flexible strategic partnership. This suppleness gives it an underlying resilience. Although the partnership is increasingly unequal, fears of Russian vassalage are overblown.

- China and Russia are strategically autonomous actors, and their influence on each other’s behaviour is limited. While they seek to undermine US primacy, their attitudes to global order diverge, and they present very different challenges to Western policymakers.

- The disruption caused by Donald Trump since his return to the White House benefits the Sino-Russian partnership. American hopes of weaning Moscow away from Beijing – the so-called ‘reverse Kissinger’ – are delusional.

- It is unclear how much the relationship can grow. An alliance is off the table for the foreseeable future, as both sides – China in particular – look to maintain strategic flexibility. Continuity is the most probable scenario, although in the longer term the widening inequality between the two partners could become a source of tension.

Introduction

In a disorderly world of shifting loyalties, the Sino-Russian partnership stands out as one of the few relative constants of international politics. For more than three decades, it has been on a steadily upward trajectory. Today, ties between Beijing and Moscow are tighter than ever, encouraging the belief among some observers that they have formed an alliance in all but name. That is debatable. What is beyond dispute is that their relationship has become a central feature of the international system.

This analysis considers the current state of the relationship and how it might develop over the next few years. The main argument is that the Sino-Russian partnership, for all its public warmth, is founded in cold-blooded strategic calculus rather than ideological like-mindedness. At the same time, this is a resilient partnership, one that will be around for some decades yet. The two sides have skilfully managed their expectations of each other and appreciate the virtues of close engagement.

The analysis seeks to answer five questions of fundamental importance. First, how have China and Russia beaten the odds and achieved a level of cooperation unmatched in the history of the relationship? What is the secret of their success? What have been the drivers of cooperation?

Second, what is the Sino-Russian partnership? A quasi-alliance, an axis of authoritarians, a vassal or clientelist relationship or, in official parlance, a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for the new era’? And how does it fit within the international system? To what extent is the partnership shaped by China’s and Russia’s respective attitudes towards global order?

Third, what has been the impact of external events on Sino-Russian relations? Has Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine brought the two countries closer or instead exposed the shortcomings of their interaction? Will Donald Trump’s attempts to appease Putin change the Kremlin’s calculus vis-à-vis China and the United States?

Fourth, what does the future hold? Will the Sino-Russian partnership go from strength to strength, or has it plateaued? How much scope is there for further growth, or is long-term decline the more likely prospect?

Finally, how should Western policymakers respond to the challenges presented by the partnership? Should they treat China and Russia as a combined and increasingly coordinated threat, or instead look to peel Moscow away from Beijing? Or perhaps it would be best to recognise China and Russia as strategically autonomous actors, and pursue an individually tailored approach towards them.

The drivers of cooperation

It is a minor miracle that the Sino-Russian partnership has emerged as one of the strongest relationships in the modern world. For there was nothing inevitable about its success. The two sides have had to transcend all manner of historical and cultural differences. Their respective world views reflect long traditions of national exceptionalism, mistrust, and xenophobia. Past cooperation has been riddled with disappointments, above all the collapse of the Sino-Soviet ‘unbreakable friendship’ in 1960 and subsequent prolonged freeze in relations. Yet despite all these impediments the partnership is flourishing.

Western commentators tend to regard the Sino-Russian partnership as being largely motivated by anti-US sentiments. In fact, the drivers of cooperation are many and diverse. They encompass mutual security reassurance, power projection, geopolitical balancing, political convergence, economic self-interest, and defence cooperation. Crucially, Beijing and Moscow would have compelling reasons to engage constructively with each other even if their relations with the United States and the West were not so dysfunctional. It is worth recalling that the Sino-Russian partnership improved steadily during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin (1991-99), despite Moscow then prioritizing engagement with the West. Likewise, in his first presidential term (2000-04), Putin expanded political, security and economic cooperation with China, even as he sought to develop closer ties with the United States and Europe. It was during this time that the long-standing territorial dispute was resolved.

The growth of Sino-Russian partnership is commonly attributed to the personal dynamic between Putin and Xi Jinping. But this is misleading. While the two leaders have injected greater dynamism into the relationship, they have not been game-changers so much as accelerants of pre-existing trends. Since the early 1990s, Beijing and Moscow have been committed to making the partnership work. What has made it strong are not individual personalities, but rather a broader consensus on both sides that it serves their respective national interests.

Security and geopolitics

The most compelling of these interests is mutual security. China and Russia share a 4,200-kilometre border, the sixth longest in the world. During the Cold War, this was an unending source of insecurity; in 1980, there were an estimated 45 Soviet divisions in eastern Siberia and the Soviet Far East, and the numbers of troops on the Chinese side were even greater. Occasionally, the confrontation turned hot, as in 1969 when border clashes over the Zhenbao/Damansky islands threatened to lead to a much larger conflict. Today, China and Russia are security partners because they cannot afford not to be. Aside from bilateral imperatives, Northeast Asia is one of the world’s most fraught security environments, encompassing not only the three leading military powers – the United States, Russia and China – but also a maverick, nuclear-armed North Korea as well as two major American allies in Japan and South Korea.

The geopolitical case for Sino-Russian partnership is commonly portrayed in terms of counterbalancing against the United States (and its allies in Europe and Asia). Yet this undersells the strategic significance of the relationship. For Moscow, partnership with Beijing is not merely about undermining American ‘hegemony’, important as this is; it is about projecting Russia as a global power. Close association with China lends credibility and legitimacy to the Kremlin’s ambitions. Without it, Russia’s stature would be considerably diminished.

Beijing’s motivations are somewhat different. It hardly needs Russia to promote China’s standing in the world; indeed, their partnership incurs reputational costs, as Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has shown. Russia is a useful partner in counterbalancing the United States and in challenging the Western narrative of a ‘rules-based international order’. But more important is that Moscow does not obstruct Chinese foreign policy goals. Xi Jinping’s commitment to expanding Chinese influence across the Indo-Pacific, Eurasia and the Arctic would be much more problematic in the face of Russian ill-will. Beijing is keen to avoid replicating the experience of the West with a power that retains the capacity and the will to cause serious disruption to the interests of others. This is one reason why Xi has taken great care to massage Putin’s sensitivities, emphasising not only the ‘equality’ and ‘mutual benefit’ of the partnership, but also the personal chemistry between the two leaders.

Having Russia as a well-disposed neighbour gives China peace of mind and room for manoeuvre, enabling it to focus on more pressing concerns at home and abroad. Chief among these priorities are contesting US primacy in East Asia and the western Pacific, and securing the reunification of Taiwan with the mainland. In pursuing these aims, Beijing expects little by way of direct assistance from Moscow. But a secure ‘strategic rear’ is indispensable to realising Chinese ambitions, and the most valuable geopolitical dividend of their partnership.

The primacy of interests

Much has been made of the authoritarian like-mindedness between Beijing and Moscow. During his presidency, Joe Biden promoted the idea of a world defined by the struggle between democracy and autocracy, and this binarism characterises constructs such as an ‘axis of authoritarians’. But such notions assign excessive importance to normative factors. True, China and Russia are ruled by authoritarian, personalised regimes that reject the liberal international order. And ideology is central to the unrelenting efforts of Xi and Putin to legitimise their rule with domestic publics, notably by propagating narratives of national ‘greatness’ – Xi’s ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ and Putin’s rewriting of the history of the Great Patriotic War (1941-45).

Beyond that, however, ideology plays a relatively modest role in the relationship. Countering US global dominance, for instance, is overwhelmingly a geopolitical priority. American hard power, not American values, is regarded as the principal threat in Beijing and Moscow. This was the case even during the Biden years. But Trump’s dismantling of US institutions and the rule of law has crippled American soft power, while in Europe liberal values are under attack from the rising tide of national populism across the continent. The normative challenge of the West to authoritarian regimes has rarely looked weaker, whereas geopolitical calculus is more salient than ever.

The interests-driven character of the Sino-Russian relationship is especially evident in the economic sphere. Bilateral trade has grown from USD 104 billion in 2020 to USD 245 billion in 2024. China has overtaken the European Union as Russia’s largest trading partner, and now accounts for 37 per cent of its total trade. This expansion owes much to circumstances – the sharp deterioration in Russia-EU relations and, specifically, the war in Ukraine. Russian energy exports to China, principally oil, have increased significantly in the wake of Western sanctions against Moscow. Beijing has taken advantage of the fall in European demand to import Russian oil at heavily discounted rates. It is a similar story with Chinese exports of consumer goods such as cars, laptops and phones. With Russian access to alternative Western suppliers more or less blocked, China has seized the opportunity to flood the market.

Defence cooperation reflects a similarly calculating spirit. The Russian war effort in Ukraine has gained considerably from Chinese components for missiles and drones, as well as from the importation of advanced machine tools for the military-industrial complex. This cooperation stems less from ideological solidarity than from the knowledge that a Putin defeat, however packaged, would be bad for China and for the health of the strategic partnership. Beijing is mindful that it still needs Russian assistance in some areas, such as missile early warning systems and advanced jet engines. And certain types of defence cooperation, such as joint naval exercises and air patrols, aim to project an image of strength to the United States and its allies.

The partnership between China and Russia benefits from not being over-burdened by sentiment. One might suppose that the unequal – and sometimes exploitative – nature of their relationship would elicit some level of Russian resentment against China. But so far there is only limited evidence of this. What matters is that their interests are complementary or can co-exist successfully. This is exemplified by their engagement in Central Asia, where the rapid expansion of China’s footprint has not led to serious friction with Russia, but strengthened bilateral cooperation. The advantages of regional accommodation – keeping the Americans out, and consolidating the Sino-Russian partnership – outweigh the urge to compete. There is an implicit recognition in Moscow that it is better off riding on the back of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative rather than attempting to stymie it, while the Chinese see no value in testing Russia’s political and security primacy in Central Asia.

Sino-Russian partnership and the international system

The label ‘strategic partnership’ has become so ubiquitous in international politics as to be almost meaningless. In the case of the Sino-Russian relationship, however, it is apt. Russia has no more valuable partner than China. And while the reverse is not necessarily true, Russia has become integral to Beijing’s world view. For both sides, the relationship is of critical importance.

The strength of Sino-Russian ties has, from time to time, encouraged some extravagant monikers, most famously the claim made at the Xi-Putin summit of February 2022 about a ‘no-limits’ friendship. The start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine less than three weeks later, and the equivocal Chinese response, underlined that there were very real limits. Another popular assertion is that cooperation between Beijing and Moscow has become so close as to represent a de facto alliance.

In reality, this is a flexible strategic partnership. One of its strengths is that it does not ask or expect too much from either side. There are none of the formal obligations that characterise political-military alliances such as NATO or Russia’s security and defence treaty with North Korea. This suppleness gives the relationship an underlying resilience. The partners are free to build or expand cooperation with a range of other countries, regardless of political or ideological affiliations. This is especially important for China, whose economic ties with the European Union and the United States far outweigh those it has with Russia. But it is also useful to Russia, for whom good relations with other non-Western countries – Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Türkiye – dilute its reliance on China.

Well before the war in Ukraine, the Sino-Russian partnership had become markedly unequal. Russia’s geopolitical and economic dependence on China has since reached new levels, which has led to claims of a patron/client or lord/vassal relationship. Such fears are exaggerated. Even at the nadir of its fortunes in the early 1990s, Russia was far from being a vassal to a geopolitically and economically dominant United States, then at the height of its power and ambition. Today, notwithstanding its many weaknesses, Russia is a much more formidable actor while China possesses nothing like the heft of the United States in its ‘unipolar moment’.

Tellingly, Xi has not indicated any interest in a hypothetical vassal-type relationship. China’s experience with North Korea – a vastly smaller and weaker power than Russia – has underlined the downsides of such an arrangement. For three-quarters of a century, Pyongyang has extracted security and economic protection from Beijing while frequently defying its wishes. It has been able to parlay the threat of US domination of the Korean peninsula and Northeast Asia to guarantee Chinese support under practically any circumstances. It is hard to imagine why Beijing would wish to replicate the experience with Russia, a country whose capacity for disruption dwarfs North Korea’s.

Western leaders are wont to blame the Sino-Russian partnership for undermining the ‘rules-based international order’. Such finger-pointing conveniently downplays the West’s own culpability. The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, the global financial crisis, the contempt for international agreements and institutions during the first Trump presidency, the myopic response of rich democracies to the Global South during the COVID-19 pandemic, and now the wild excesses of Trump 2.0 – have all been stages in the unravelling of international order. This is not to absolve China and, in particular, Russia of their share of responsibility, but it is not credible to attribute the crisis of global order to their partnership.

Blaming the Sino-Russian partnership for a disorderly world also buys into the myth that Beijing and Moscow have identical or near-identical views of global order. Their approaches could hardly be more dissimilar. Although the Chinese leadership seeks to undermine US primacy and maximise Chinese influence, it does so by working predominantly within the international system, from which it continues to benefit enormously. Beijing invests considerable effort in multilateral diplomacy, both within and outside the United Nations, because it sees this as necessary to operating in a world that is more interdependent and globalised than ever. China is a revisionist power, but it is not a wrecker. Although its respect for rules is highly selective and arbitrary – not unlike the United States – it regards global order as an essential framework for promoting Chinese interests.

Compare this to Putin’s Russia, which has been the principal disruptor of the international system for the best part of two decades. During that time, it has twice invaded Ukraine; effectively annexed parts of Georgia (Abkhazia and South Ossetia); intervened militarily in Syria, including supporting the use of chemical weapons; interfered directly in numerous overseas elections; undertaken clandestine military activity in several African countries; conducted an active programme of overseas assassinations; and engaged in major disinformation campaigns. No other country in the world – including so-called rogue states such as Iran and North Korea – can ‘boast’ a comparable record.

It is a singular feat of the Sino-Russian partnership that it has been able to accommodate such contrasting approaches to international order. Nevertheless, this divergence highlights an essential truth: China and Russia are strategically autonomous actors. Theirs is a traditional great power relationship grounded in realpolitik. Xi may claim that together they are driving changes in the world, ‘the like of which we haven’t seen for 100 years’. But the reality is more prosaic. Beijing and Moscow conduct independent foreign policies, which frequently differ from each other in content and style. Their influence on the other’s decision-making is strictly circumscribed. Each side has its own particular interests and priorities. The strategic partnership is an important tool and framework in assisting these endeavours, but it is only one element among many in Chinese and Russian foreign policymaking.

The shock of events

The Sino-Russian partnership is shaped primarily by the logic of cooperation and the world views of Beijing and Moscow. It has also been impacted by external shocks. However, rather than being game-changers, such shocks have accentuated the pragmatic, unsentimental nature of Sino-Russian engagement. This has been evident in the course of the war in Ukraine and in response to Donald Trump’s return as US president.

The war in Ukraine

The conflict in Ukraine has exposed significant differences in Chinese and Russian attitudes on core principles of international order, such as the sanctity of national sovereignty and the non-use of force against other states. It has also revealed shortcomings of trust and confidence in the bilateral relationship. Thus, at their February 2022 summit, Putin most likely informed Xi about the impending ‘special military operation’, but not of its scope. The Chinese government was clearly surprised by the scale of the invasion, given its failure to make any preparations to evacuate some 6,000 Chinese students in Ukraine. It was even more shocked – and dismayed – by Russia’s subsequent military setbacks. Against an opponent substantially inferior in size of force and economic capacity, the aura of Russian ‘greatness’ soon dissipated.

Although some Western commentators believe that China has been a major beneficiary of the war, this judgement is questionable. Putin’s decision to launch a full-scale invasion and Moscow’s subsequent failures had a number of adverse consequences for Chinese interests. They emboldened the United States and strengthened its alliances in Europe and Asia. They inflicted further damage on China’s relations with Europe. They weakened Beijing’s leverage over Taiwan by highlighting the logistical and political constraints on large military operations. And they posed uncomfortable questions about the closeness of China’s partnership with a delinquent power. Later, as the tide of the war turned in Russia’s favour, Beijing became disconcerted by other aspects of Putin’s behaviour, in particular his ready resort to nuclear blackmail and outreach to Kim Jong-un for military support. The active deployment of North Korean troops in the war has embarrassed and irritated Beijing. More generally, Putin’s intransigence has stripped away any illusions that China might be able to moderate his actions.

Nevertheless, despite all these inconveniences and worse, Xi has sided with Putin during the latter’s time of crisis. The Chinese may have deplored his misjudgements, but not to the extent of abandoning him or even adopting a neutral stance. Beijing, like Moscow, views the war as essentially a zero-sum confrontation between Russia and the West. To have taken Kyiv’s side and condemned the violation of Ukrainian sovereignty would have been to support the United States against China’s only true strategic partner – difficult at any time, but unthinkable against the backdrop of the worst crisis in China-US relations in half a century. Moreover, Beijing would have received little credit for adopting a principled position. China would have been left with a still hostile United States, a resentful and potentially vindictive Russia, and a largely impotent Europe.

For the first year or so of the war, Xi attempted to square his commitment to the Sino-Russian partnership with limiting the damage to China’s relations with the United States and Europe. But by 2023 this balancing act had been overtaken by three major developments: Russian successes on the battlefield, notably in stalling the much-touted Ukrainian counter-offensive; growing signs of ‘Ukraine-fatigue’ in the West; and the rising irritation of Global South countries at the diversion of attention and resources away from priorities such as climate financing and debt relief. In these changing circumstances, Beijing has become more open in backing Moscow.

Western policymakers and thinkers argue that Chinese material support has enabled Putin to sustain the war. The picture, however, is mixed. On the one hand, Chinese assistance has boosted Russia’s military prospects. The provision of dual-use components, especially for drones and missiles, has helped its armed forces to fight more effectively. Beijing has also enabled Russia to circumvent and mitigate the impact of Western economic sanctions. And it has been instrumental in shifting the global debate about the war. Whereas at the beginning of the conflict, the focus was predominantly on Putin’s flagrant breach of international norms, by 2023 the dominant narrative across the Global South was of Western hypocrisy, double standards, and general disregard for developing country priorities.

On the other hand, the implication that without Chinese support Putin might have been forced to sue for peace is dubious. It underestimates his desperation to prevail regardless of the human and financial costs. And it overestimates Beijing’s influence on Kremlin decision-making. Despite their support for Putin, the Chinese nevertheless hope for an early end to the conflict. A rapprochement with leading European countries has become all the more urgent since Trump’s return to the White House, and continuation of the war is a major impediment to improved relations. But Putin has no intention of allowing Chinese concerns to deflect him from the pursuit of ‘victory’. He has tied his political well-being and future legacy to the outcome of the war; no sacrifice – by others – is too great.

Beijing is currently in something of a holding pattern on Ukraine. It continues to back Moscow because it sees no viable alternative; a Putin defeat equates to victory for the West. At the same time, China has sought to boost its ‘peace’ profile through various statements calling for a resolution of the conflict. The purpose of these initiatives is essentially performative; Beijing has neither the credibility nor the heft to broker a meaningful peace. Rather, it uses such diplomacy to promote China’s credentials as a responsible power to a Global South audience impatient to move on from Ukraine.

The Trump effect

In the space of just a few short months, the second Trump presidency has come to be seen as a total game-changer for international order. This has included conjecture about its impact on the Sino-Russian partnership. Will the most pro-Kremlin – and anti-Beijing – president in US history succeed in overturning the strategic calculus that has underpinned this relationship for more than two decades? Certainly, there are high hopes in Washington of peeling Putin away from Xi, and of isolating China.

Such optimism is misplaced. Ironically, the disruption initiated by Trump since his return to the White House is great news for the Sino-Russian partnership. Amidst a world in ferment, the stability it offers has never looked more attractive to both sides.

The Kremlin is potentially the greatest beneficiary of Trump 2.0. But hardly in the way imagined by the White House. All the signs are that Putin believes he can have it all: victory over Ukraine, its de facto extinction as a sovereign state, the emasculation or demise of NATO, an end to the post-Cold War order in Europe, a ‘pragmatic’ relationship with the United States, and the emergence of a tripolar world in which Russia is the geopolitical pivot between the United States and China. Moreover, all this appears achievable with minimal quid pro quo, even if it will take some time. Putin will look to exploit Trump’s weaknesses – vanity, ignorance, naivete – to secure a ‘deal’ with the White House that would not only undermine US and European foreign policy but also adjust the balance of power within the Sino-Russian partnership. Opening up additional foreign policy options would eliminate any risk of being taken for granted in Beijing.

The bottom line, though, is that Russia cannot afford to allow relations with China to degrade. The considerations that make their partnership so important remain as relevant as ever: mutual security reassurance and a long common border; China’s multiplier effect on Russian global influence; close economic ties; and defence cooperation. No American president can, much less will, match this package. And however well-disposed Trump may be towards the Kremlin today, there is every chance that his successors, Republican or Democrat, will revert to the mean and either treat Russia as a hostile power or seek to marginalise it. Trump’s own record gives little reason for confidence. His so-called ‘transactionalism’ is almost entirely zero-sum, and any ‘deals’ that are agreed can – and often are – abrogated or ‘re-negotiated’. In the circumstances, it is virtually inconceivable that Putin (or a successor) would surrender the sure thing of partnership with China for the speculative hope of accommodation with the United States.

The Chinese know this. Far from being anxious that Russia may re-orientate its foreign policy, they are confident that the strategic partnership will be as strong as ever and may even expand further. The mayhem unleashed by Trump has allowed China to promote itself as the guardian of international order. This message reverberates not only among non-aligned countries, but even among some of America’s allies. As the transatlantic alliance erodes, and the idea of a unitary ‘West’ loses credibility, Beijing’s strategic opportunities are multiplying. Despite the economic impact of American tariffs, Trump is the gift that keeps on giving. The more chaos he causes, the better for China overall – and that includes its partnership with Russia.

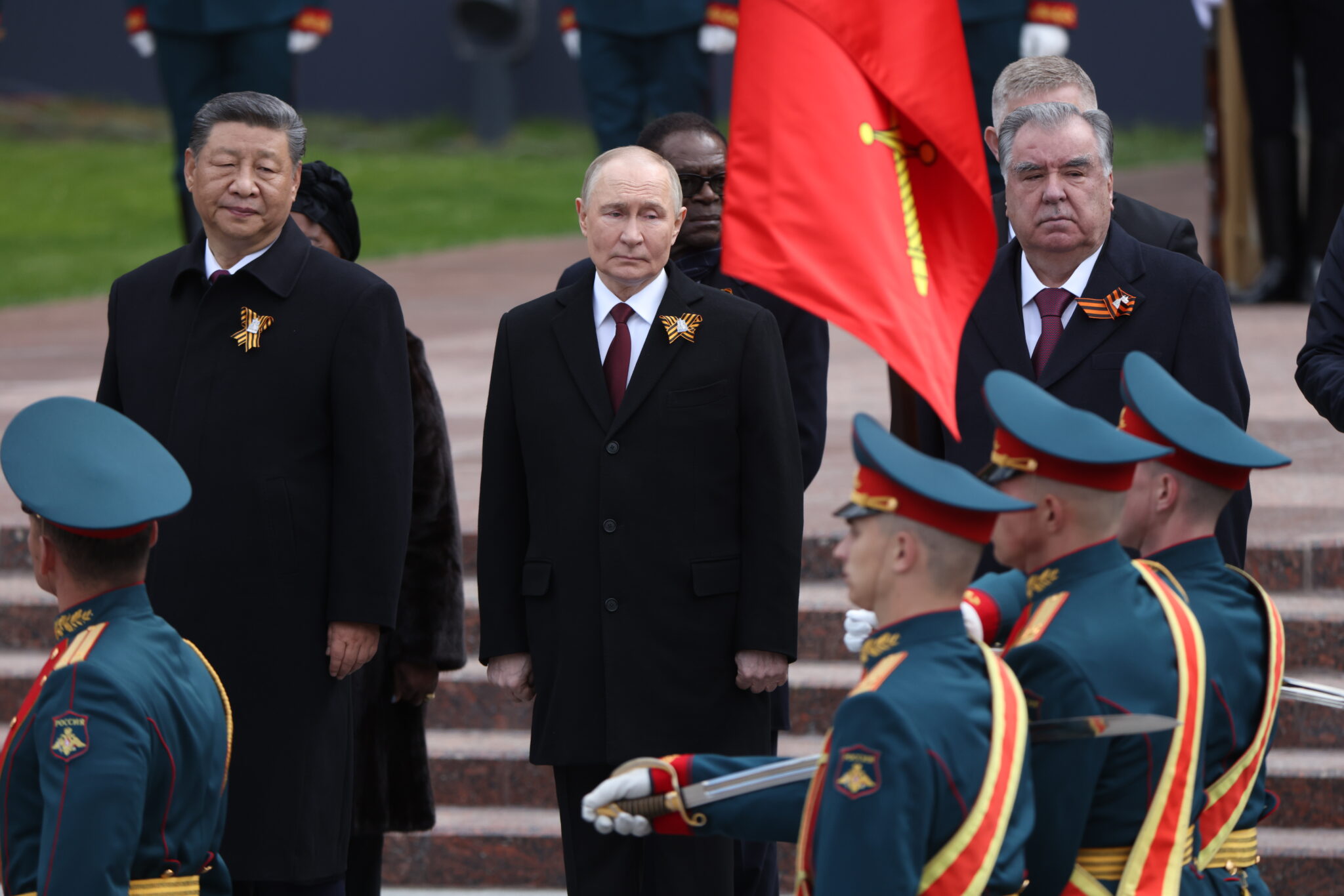

Looking ahead

The format of a flexible strategic partnership has consistently demonstrated its worth. Although Putin’s war on Ukraine has highlighted the limits of Sino-Russian cooperation, the relationship is emerging from it in better shape than ever. There is nothing to indicate that American efforts to ‘un-unite’ China and Russia will bear fruit. On the contrary, Xi’s recent visit to Moscow for the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, during which the two presidents issued a joint statement on global strategic stability, suggests that the outlook is set fair.

The more interesting question is how much the two sides can build on existing levels of cooperation. One nightmare scenario envisaged by Western planners is of China and Russia engaging in parallel conflicts in Asia and Europe. This activity need not necessarily be coordinated. Putin could, for example, take advantage of a US-China confrontation over Taiwan or in the South China Sea to launch further military operations on Europe’s periphery and against the Baltic states. Equally, Xi could use Putin’s continuing aggression as a blind behind which to launch an invasion of Taiwan.

Such eventualities appear alarmist. The fact that China and Russia are strategically autonomous actors suggests that any operations either partner may conduct will be contingent not on unpredictable developments several thousand miles away, but on factors closer to home. That is particularly true of China, which has not fought a foreign war since it launched a short-lived incursion into northern Vietnam in 1979. One of the lessons from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is that even under highly favourable conditions – easy terrain, pre-deployment of large concentrations of troops, far superior numbers and materiel – subjugating a country is a hugely challenging and risky enterprise. Compared to Ukraine, the logistics of a military operation against Taiwan would be exponentially harder, US strategic interests more directly involved, and the political sensitivities in Washington more acute. It is implausible that Xi would contemplate an assault against Taiwan on the off chance that America might be too distracted by events in Europe to respond effectively.

The timing of an invasion is more likely to be determined by Beijing’s assessment of the correlation of forces in the western Pacific; domestic developments in Taiwan, for example, a unilateral declaration of independence by its president Lai Ching-te; political pressures in Beijing; and Xi’s desire to secure reunification during his lifetime. Even then, the Chinese leadership would need to factor in the possibility that an attack on Taiwan might result in a disastrous war with the United States, one that could set China’s growth back several decades and even topple the Communist Party.

The separate possibility that Putin may undertake further military adventures is, however, a compelling argument for Beijing to retain the current flexible format of relations. The Chinese leadership does not want to be put in a position where it is at the mercy of the Kremlin’s reckless decision-making and under pressure to come to its aid. It is one thing to support Russia indirectly over Ukraine; it is quite another to back it in a direct conflict against the West. For this reason alone, a political-military alliance is improbable. The risks of China being dragged into a future conflict not of its making would be unacceptably high.

It may be that the Sino-Russian partnership has reached a ceiling. With an alliance off the table, it is hard to see how and where a quantum leap might occur. Continuity is the most probable scenario, but the relationship could also degrade over time. Several long-term issues will need to be carefully managed in the coming decades. One is the growing disparity in capabilities and influence between the two countries. Although the inequality of the partnership has not proved a major problem thus far, there is the question of degree.

If China sustains its rise as the next multi-dimensional global power while Russia stagnates or declines, the widening gap may become a real source of tension. Inequality would not just be a problem in the abstract, but could have concrete implications in Central Asia, Northeast Asia, the Arctic, and even the Russian Far East. As Putin has shown over Ukraine, bilateral agreements do not guarantee lasting borders. There is no evidence of any plans in Beijing to recover the ‘lost one-and-half million square kilometres’ ceded to Russia as a result of the ‘unequal treaties’ of the 19th century. And such a venture would be fraught with risk. But, as circumstances change over time, so might Chinese intentions – and the level of Russian suspicion.

Another point of divergence and friction may be over the shape of global governance. Although Beijing and Moscow speak of a multipolar order, their understanding of this differs markedly. For the Chinese, the United States represents the benchmark, whereas Russia is indubitably an inferior power. Beijing’s vision is not multipolar as it claims, but more akin to a G-2 plus centred on the US-China dynamic, with other powers playing secondary or subordinate roles. By contrast, in the Kremlin’s tripolar vision Russia is due all the prerogatives of a first rank power, equal to America and China. Until now such differences have been glossed over, but it would be unwise to assume this will be the case indefinitely.

As unlikely as it seems today, we should also consider a post-Putin scenario whereby Russia re-enters the international mainstream as a more ‘normal’ power with a renovated foreign policy. This might be characterised by functional relations with America and Europe, greater diversification of foreign ties, and transition from a militaristic and imperialist mindset into a more agile and pragmatic approach to the world. If this paradigm shift were to occur, one consequence would be a reduction, in relative terms, of China’s place in Russia’s international relations.

It is important to emphasise, though, that any such transition would not be rapid. For some time yet, China and Russia will have no more reliable partner than each other. Despite the differences in their world views and approaches to international order, the relationship is too valuable to discard or neglect. And this will remain the case well after Xi and Putin have left the political stage.

Implications for Western policymaking

In responding to the challenges of the Sino-Russian partnership, Western leaders should understand that their capacity to directly influence decision-making in Beijing and Moscow is extremely limited. It is futile, for example, to point out to the Kremlin that Russia would benefit from reducing its reliance on China, or to Beijing that it should distance itself from Moscow. Holding out the vague promise of ‘better’ relations with the West as a reward is to treat Putin and Xi as foreign policy ingenues.

It is likewise absurd for the United States to identify Russia as the less threatening and more biddable party in the strategic partnership. Some of China’s actions in recent years have breached international norms, notably in relation to South China Sea territoriality. But its record of transgressions pales in comparison with Russia’s serial rule-breaking, appetite for risk, and extraordinary level of violence. One government retains a commitment to some sort of order; the other ceased pretending years ago. The opportunities for the United States and other Western governments to engage productively with China are infinitely greater than they are with a militarised and destructive Russia under Putin.

The ‘reverse Kissinger’ strategy, attempting to draw Putin away from Xi, is a recipe for failure. This type of appeasement not only misremembers the logic that informed the original Nixon/Kissinger initiative to bring Mao Zedong’s China onside, it is also counterproductive. The notion that Putin can be persuaded to loosen ties with Beijing hands him leverage for free. He is able to hold out the threat of cozying up closer to Xi, pocket any American concessions, and sustain the Sino-Russian partnership on even better terms than before. Far from strengthening Washington’s hand, what passes for ‘strategic diplomacy’ incentivises Moscow and Beijing to double down on their partnership.

Treating China and Russia as a conjoined entity that is ‘greater than the sum of its parts,’ is no less ill-advised. They are individual powers that present distinctly different policy challenges that should be addressed in their own right. In this connection, the spectre of Sino-Russian domination of a single Eurasian strategic space, extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific, is an abstraction without merit, as are constructs like ‘axis of evil’, ‘democracy versus autocracy’ and ‘axis of upheaval’.

An effective response to the Sino-Russian partnership needs to move away from ideologically driven generalities and concentrate on addressing specific threats – whether it is Chinese maritime aggression, trade dumping, and cyber activity, or Russia’s efforts to subvert democratic politics in Europe and overturn the post-Cold War settlement. Conflating these two sets of challenges is a sure way of dealing with neither.

Western policymakers should make full use of the tools at their disposal, above all an extensive network of alliances and partnerships. This is self-evident, yet they have singularly failed to do so. Instead, Trump’s disparagement of NATO and the European Union, Washington’s ongoing betrayal of Ukraine, US interference in European elections, and European prevarication and timidity, have reinforced perceptions of an imploding ‘West’, divided and bereft of political authority. If this trend continues, there will be little to discourage Chinese and especially Russian misbehaviour. The onus is on Western countries to prove, to themselves and others, that they are able to coordinate effectively in response to the many challenges facing them.

It is a truism that power and influence stem from performance at home as well as abroad. The best way democracies can compete with authoritarian regimes in the long run is to demonstrate superior governance based on principles such as the rule of law, democratic accountability, and social and economic justice. But in recent times they have done just the opposite. Nothing boosts the legitimacy of Chinese Communist Party rule or the Putin regime more than the spectacle in the West of political polarisation, government dysfunction, worsening corruption, demagogic populism, and culture ‘wars’. The unravelling of democratic norms and institutions in Trumpian America is far more destructive to Western interests than anything Beijing or Moscow can do, individually or in tandem.

Finally, a functional approach in response to the Sino-Russian partnership must comprise elements of a positive agenda. It cannot all be about retaliation, deterrence and containment. Working with Beijing on, say, climate policy, debt relief, global health, conflict management, and counter-narcotics offers considerably better prospects for Western interests than slapping swingeing tariffs on Chinese goods or condemning it out of hand as a ‘malign actor’. Of course, cooperation comes with its difficulties and frustrations, and progress is likely to be painstaking at best. But there is no sensible alternative. Addressing critical global challenges, including geopolitical confrontation, involves searching for common ground with systemic rivals. We do not have the luxury of cooperating only with our friends.