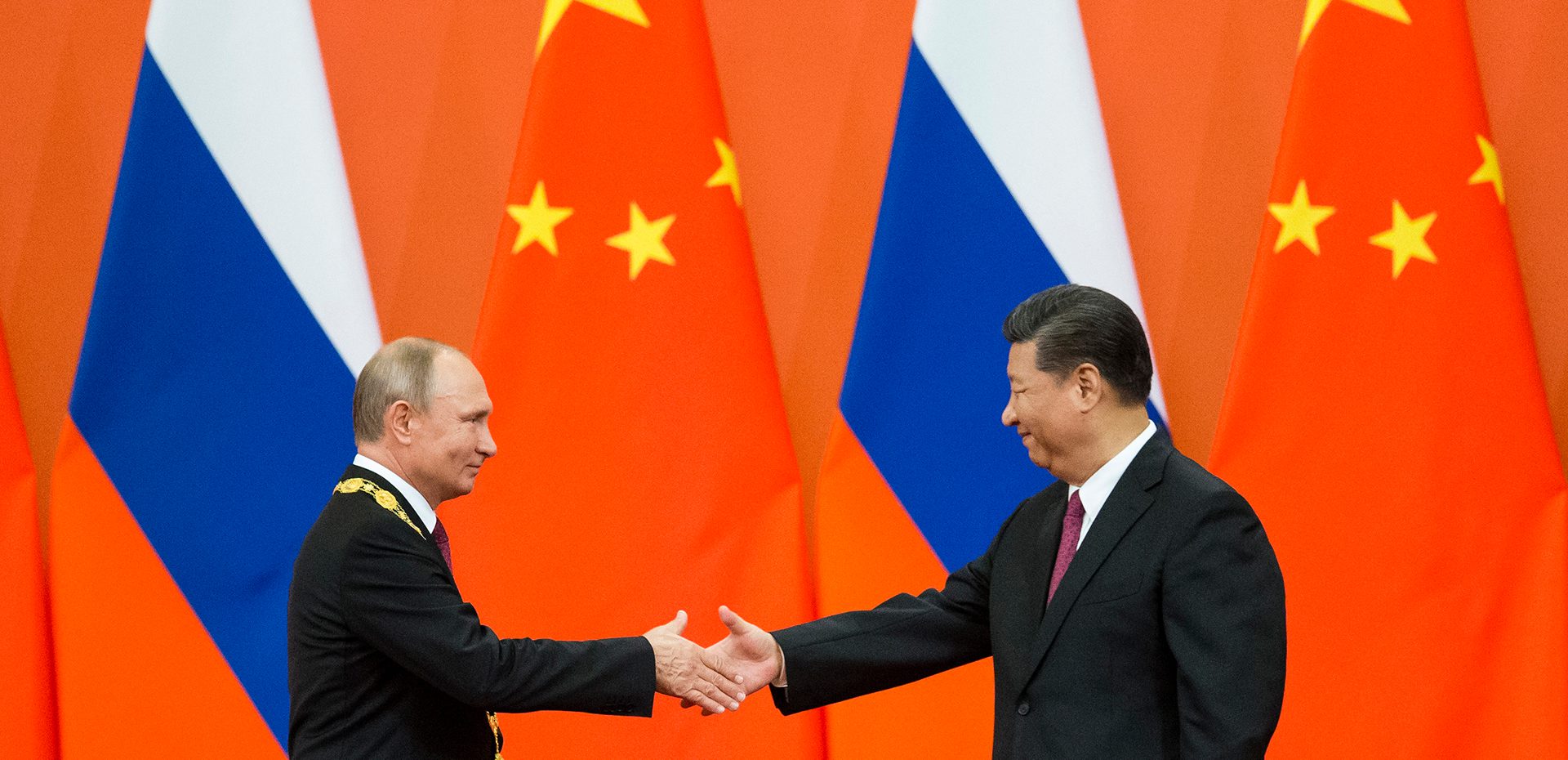

Marriage without love: The Sino-Russian partnership and what it means for the world

Summary

- The Russia–China partnership should not be viewed as a deliberate or inevitable strategic alliance. The current, unusually close alignment between Russia and China is reactive in nature and is largely driven by both countries’ confrontation with the West, and, in Russia’s case, by the consequences of its war against Ukraine.

- Interpreting this relationship as a unified anti-Western front is misleading. Moscow and Beijing pursue different long-term objectives. China acts as a pragmatic revisionist power, focused on achieving a managed transformation of the international order to advance its role in the global economy. Russia, by contrast, relies primarily on military power and seeks recognition of its veto over any situation it perceives as affecting its interests.

- Interaction between Russia and China remains transactional and limited in scope. It includes military-technical cooperation and foreign policy coordination, but is marked by persistent asymmetry, with Russia in a subordinate position.

- Economic ties between Russia and China, based on the complementarity of their economies, are relatively resilient but appear close to their upper limit. Bilateral trade is highly dependent on global oil price dynamics and has not translated into broad-based investment or technological cooperation. China avoids long-term commitments, treating Russia as an undesirable competitor in industrial manufacturing, but a useful supplier of raw materials.

- Shared anti-Western positions do not offset mutual distrust shaped by historical traumas and cultural distance. Even as these factors gradually weaken, they are likely to constrain any deepening of relations at least over the medium term.

- In the political sphere, the most likely medium-term scenario is a stable but limited partnership, largely declaratory in nature. The formation of a genuine military-political alliance between Moscow and Beijing remains highly unlikely.

- The absence of clear Western strategies towards Russia and China increases the risk of an unintended negative outcome: deeper Russian dependence on China. This scenario is undesirable for Beijing, but could be induced by external pressure.

Context

Russia’s pivot to China began in 2014 and accelerated after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. While the war has had sharply different effects on the two countries, it has not disrupted their bilateral relationship.

China has emerged as the principal beneficiary. The conflict has distracted the US from Indo-Pacific deterrence, weakened Europe, and enabled Beijing to expand its economic presence in Russia by replacing Western firms and securing discounted energy imports. Russia’s isolation has increased its dependence on Chinese markets and technology, making Moscow more vulnerable to Beijing’s leverage. At the same time, China has been able to observe modern warfare without direct involvement.

For Russia, the war has produced substantial strategic and economic losses. Sanctions have dismantled its economic relationship with the West, forcing an inefficient reorientation towards Asian markets and resulting in the loss of Europe as a long-term gas customer. Rising military expenditure has distorted the economy, fuelled inflation, and reduced civilian investment, while skilled emigration has intensified the brain drain. Russia has also lost influence across parts of the former USSR, while NATO enlargement and Europe’s renewed defence efforts have worsened its security environment.

The nature of the Sino–Russian relationship

The relationship between Russia and China is best understood not as a strategic alliance, but as a pragmatic alignment shaped by necessity, opportunism, and shared opposition to Western influence. While Moscow portrays it as a historic geopolitical realignment, Beijing treats Russia as a secondary partner within a broader global strategy centred on stability and managed competition with the United States.

The partnership is structurally asymmetrical. Russia has become increasingly dependent on China as its main trading partner, supplier of critical goods and technologies, and economic lifeline under sanctions. China faces no comparable dependence and retains clear leverage. Economic ties remain narrow and transactional: Russia exports primarily energy and raw materials, while China supplies manufactured goods and technology. This relationship has not developed into sustained investment or deep technological integration, reflecting Beijing’s caution about long-term exposure to Russian risk.

Political coordination is real but limited. Both states seek to constrain Western influence, yet their long-term objectives diverge. China aims to reshape the international order through gradual reform while preserving the global economic system. Russia, by contrast, has embraced disruption and geopolitical volatility as instruments of influence, often conflicting with Beijing’s preference for predictability and stability.

These features point to a partnership that is resilient in the short term but limited in depth. The central question for Western policymakers is not whether Moscow and Beijing will form a formal alliance, but how far Russia’s dependence on China will deepen, and what this growing imbalance will mean for Eurasian security.

Political partnership

Political cooperation between Russia and China has intensified since 2022, with both governments presenting the relationship as a pillar of an emerging multipolar order. Frequent high-level meetings, regular summits, and coordinated rhetoric against the ‘Collective West’ reinforce the image of strategic alignment.

In practice, however, the partnership remains largely tactical. Beijing does not treat Russia as a central priority, but as a useful partner that can help to constrain Western pressure while providing energy security and diplomatic leverage. Moscow, by contrast, has elevated China to the role of a strategic lifeline, framing the relationship as evidence that Russia cannot be isolated.

China’s approach is pragmatic rather than ideological. Beijing does not seek institutional or alliance-based integration, nor does it export its political model. Its core expectation is limited: Russian support for China’s key sovereignty claims, particularly on Taiwan, combined with non-interference in China’s domestic trajectory. Beyond this, Beijing avoids binding commitments that could restrict its flexibility or damage relations with Europe and regional partners.

The political partnership is therefore durable but shallow. It is sustained by short-term convergence and shared opposition to Western dominance, yet constrained by deep asymmetries, diverging strategic visions, and China’s consistent preference for autonomy over alliance obligations.

Economic cooperation between China and Russia

Economic ties form the backbone of the Sino–Russian relationship, but they fall short of genuine integration. Bilateral trade has expanded rapidly since 2022, with China accounting for a dominant share of Russia’s exports and imports. This growth reflects wartime necessity rather than strategic economic convergence.

Trade is increasingly asymmetrical on a classical model of exchange of commodities for finished products. Russia exports oil, gas, coal, and other raw materials, while China supplies manufactured goods, machinery, electronics, and transport equipment. The loss of Western markets has accelerated this pattern, reinforcing Russia’s role as a resource supplier rather than a technological peer.

Despite rising trade volumes, Chinese investment in Russia remains limited. Beijing continues to avoid long-term commitments, minimises its exposure to sanctions risk, and shows little interest in transferring advanced technologies that could make Russia an industrial competitor. Large-scale joint projects have repeatedly stalled or reverted to buyer–supplier arrangements, highlighting the limits of cooperation beyond trade.

China’s economic engagement has nevertheless played a stabilising role for Russia amid the hurricane of Western sanctions. Chinese exports have helped to sustain industrial production and, in some sectors, supported the defence-industrial base. Yet Beijing’s approach remains transactional, offering access where it is commercially advantageous while carefully limiting strategic dependence on Moscow.

The Chinese presence in Russia

China’s expanding role in Russia has become increasingly visible since 2022. As Western companies withdrew, Chinese firms filled gaps in sectors ranging from cars and electronics to telecommunications. For many Russian consumers, Chinese products have become the primary substitute for lost Western alternatives, reinforcing perceptions of China as an indispensable economic partner.

Public attitudes in Russia have shifted accordingly, but remain pragmatic rather than ideological. China is viewed as a buffer against the pressure of sanctions, driven by material gain rather than deep political or cultural affinity.

At the same time, greater economic proximity has not translated into societal closeness. Historical legacies and mutual suspicions continue to limit trust beneath official rhetoric. Cultural exchange has expanded through state-sponsored initiatives and the growing popularity of Asian media among younger Russians, but much of this engagement remains symbolic and superficial.

Concerns persist in Russia about long-term dependence, sovereignty, and China’s expanding influence, particularly in the Far East. Chinese migration remains limited and concentrated in tourism, education, business networks, and project-based employment rather than permanent settlement. Overall, China’s presence in Russia is growing, but economic interdependence is advancing faster than social or cultural integration.

Military cooperation

Military cooperation between Russia and China has become more visible since 2022, but it remains far from a formal alliance. Joint exercises, defence contacts, and symbolic demonstrations of coordination have increased, reinforcing perceptions of a tightening relationship. There is, however, little evidence of deep operational integration let alone binding security commitments.

China continues to avoid steps that would tie it directly to Russia’s war effort or expose it to extensive secondary sanctions. It has not provided overt military assistance on a scale consistent with an alliance relationship, and its defence engagement with Russia remains shaped by risk management and strategic caution.

At the same time, China has played an important indirect role in sustaining Russia’s military-industrial capacity. Exports of dual-use goods, industrial equipment, and technological components have helped Moscow to compensate for Western restrictions, particularly in areas such as electronics, drones, and machine tools. This support has allowed Russia to mitigate sanctions-related shortages while enabling Beijing to maintain plausible deniability.

Mutual distrust further constrains deeper defence cooperation. Russia remains reluctant to share sensitive capabilities, while China prioritises self-reliance and avoids dependence on Russian military technology. As a result, the security relationship remains selective and transactional.

Challenges to Sino–Russian relations

Despite its resilience, the partnership faces several structural constraints:

- Growing inequality. China’s continued modernisation contrasts with Russia’s stagnation under sanctions, reinforcing an increasingly unbalanced relationship.

- Dependence and resentment. Beijing benefits from discounted energy and market leverage, while Moscow risks accepting junior-partner status that conflicts with its great-power self-image.

- Diverging visions of global order. China prioritises stability and managed reform, while Russia increasingly relies on disruption and geopolitical volatility.

- Limits of Chinese support. Beijing does not want Russia to be defeated in Ukraine, but also seeks to avoid outcomes that would destabilise Europe or harm Chinese economic interests.

- Competition in third regions. In Central Asia, the Arctic, and parts of the Global South, China’s expanding footprint increasingly overshadows Russia’s influence.

- Persistent mistrust. Historical legacies, cultural distance, and weak societal ties continue to limit deeper integration.

Overall, the partnership is likely to remain durable but constrained, driven by tactical convergence rather than strategic unity.

Scenarios

Several trajectories are plausible over the next five to ten years:

- Baseline scenario: Transactional partnership (high probability). Cooperation remains broad but shallow, driven by the pressure of sanctions and by mutual convenience. No formal alliance emerges, and Russia’s dependence on China continues to deepen.

- ‘Vassalisation’ of Russia by China (medium probability). Prolonged war and economic degradation increase Russia’s reliance on China as its primary buyer, supplier, and technological gatekeeper. Moscow tolerates growing imbalance in exchange for regime stability.

- Strategic alliance (low probability). Amid extreme escalation of US–China confrontation and the sustained isolation of Russia, the two states move towards more formalised security alignment. This scenario remains unlikely given the high costs for China.

- Weakening of the partnership (low probability). If the war in Ukraine ends and external pressure eases, the relationship may lose momentum. Russia could seek limited re-engagement with the West, while China recalibrates its priorities, although a full ‘return to Europe’ remains improbable.

The most likely outcome is continued transactional cooperation marked by deepening asymmetry rather than alliance formation. For the West, the primary strategic risk lies not in a unified bloc, but in Russia’s growing structural dependence on China.