Putin’s dilemma: war or peace?

Putin believes he is winning in Ukraine, but a swift victory is uncertain. Russia can keep fighting, yet labour shortages, equipment losses, and economic strain are mounting. The Kremlin depends on passive public support and a centralised elite; foreign allies help sustain its war effort. Meanwhile, a narrow window for diplomacy remains.

Summary

- Putin believes he is winning his war against Ukraine, but quick victory is not assured. He can carry on fighting for at least one to two years, but continuation of the war will gradually exacerbate problems and reduce the margin of comfort that currently exists.

- The economy has proved resilient in the face of Western sanctions and increased military spending, but labor shortages and the draining of resources from the civilian sector are storing up serious long-term problems.

- Military industry is working flat out and, with the help of China, Iran and North Korea, the army is sufficiently equipped for now to continue fighting at current levels of intensity. However, equipment losses are set to become a more pressing issue and will require greater assistance from allies to address it.

- The army also faces a manpower problem if the war continues and losses remain at current levels. This could require further mobilization that Putin would prefer to avoid because of its unpopularity.

- The Kremlin relies heavily on society’s passive support for the war. There are no signs that this is diminishing. Demobilization could create serious socio-political problems if well-paid soldiers return to a low-wage civilian economy.

- The elite is united with no signs of internal dissent. Management of the nomenklatura bureaucracy is now much more centralized on a model that is set to outlive Putin.

- Russia can continue to rely on China, Iran and North Korea for support for its military machine, while India and Turkey will continue to buy its oil at discounted prices—helping stabilize the Russian economy.

- A narrow window exists for U.S. diplomacy to help negotiate an end to the war. These efforts must be backed by a display of strength.

- Russia is preparing for long-term confrontation with the West beyond a ceasefire or peace settlement in Ukraine.

Introduction

Nearly three years into his full-scale war against Ukraine, Vladimir Putin believes that he is winning. He sees the prospect of complete victory, achieving his goal of bringing to power in Ukraine a “friendly” government that respects Russia’s interests, abandons integration into the EU and NATO and agrees to the country’s “demilitarization.” This will be a victory not just over Ukraine but over its Western allies as well.

For the Kremlin, inflicting a humiliating defeat on the West will teach it to accept Russia’s supremacy in its immediate neighborhood and recast the European security system to Russia’s advantage.

Yet there is a major potential obstacle. Although the return of Donald Trump to the White House brings the welcome prospect for the Kremlin of disruption on multiple fronts and might even accelerate victory over Ukraine, Trump’s stated determination to end the war quickly could potentially delay the full victory that Putin craves. It might also make it impossible, depending on the requirements that Washington sets.

The stakes are particularly high for Putin because stopping the war could create serious problems at home, especially if peace terms do not meet the expectations set. However, as a negotiating process starts with the U.S., Putin can feel justifiably confident at several levels:

- Military advantage. The Russian war machine is slowly but surely degrading Ukraine’s resilience. The Ukrainian army is retreating along large parts of the front line and the Zelensky administration is struggling to mobilize enough soldiers to keep fighting. Ukraine’s population is exhausted and suffering increasingly from the damage inflicted by Russia’s targeting of critical infrastructure. Zelensky’s Churchillian moment has passed, and the notion of a Ukrainian “victory” is no longer seriously discussed in Kyiv.

- Western disarray. Three years into the war, Ukraine’s Western partners still have no strategy to guide their support for the country. They have failed to restart their defense industries so they can supply the Ukrainian armed forces without undermining their own military capacity. Trump’s reelection means that Europeans must now take responsibility for Europe’s security as the U.S. reduces its financial commitment to their defense, but they lack the resources to do so.

- Domestic stability. Domestically, Putin’s regime is stable even if it is potentially fragile. It can rely on society’s passive support while the instruments of repression work to limit dissent. Admittedly, the economy is under pressure with inflation an increasing concern but overall, it has adapted to the immediate effects of Western sanctions and found enough workaround to keep industry functioning. The defense-industrial complex is facing some serious challenges, but these have not so far impacted the war effort.

- Geopolitical backing. China and India continue to buy Russian oil, and while Beijing may have limited enthusiasm for the war, it is still an important channel for the supply of dual-use equipment and technologies. The pariah duo of Iran and North Korea continues to provide military equipment and, more recently in the case of Pyongyang, manpower, to support the war effort.

Putin believes that Russia and its allies have already made a strategic breakthrough at a global level by demonstrating that the Western-dominated international order is irretrievably broken and must be replaced by a “democratic” arrangement that represents the interests of major non-Western countries. In his view, victory over the West in Ukraine will accelerate this revolutionary process that has placed Russia in a position of strategic advantage vis à vis the West, after decades of disadvantage. To consolidate this anticipated victory, Putin is preparing for long-term confrontation with the West.

Paradoxically, the success that the Kremlin believes has been achieved at this level has not yet been matched on the ground in Ukraine by the Russian army. Against all predictions, Ukraine’s defenses have so far held up and its biggest cities outside Donbas remain under government control. Nevertheless, Putin clearly believes that with the prospect of the U.S. denying Ukraine further large-scale military support and the Ukrainian army struggling to address its manpower problem, Russia will sooner or later be able to force Ukraine to surrender.

To this extent, the re-election of Trump presents Putin with both an opportunity and a risk. The opportunity derives from the possibility of turning Trump into an agent of Ukraine’s defeat by encouraging him to persuade Kyiv that there is no alternative to signing a peace agreement on Russian terms. The risk is that agreeing to a compromise peace formula, one that is deemed acceptable by Trump and that the new U.S. Administration could impose on Ukraine and its European allies, would fall short of Putin’s need to demonstrate victory. Trump cannot afford to look weak in the eyes of the Chinese, North Koreans, and others.

In short, Putin faces a dilemma: to stop the war or to continue fighting. Put simply, stopping the war without achieving the declared objectives of changing Ukraine’s leadership and “demilitarizing” the country would damage Putin’s authority, especially among the Russian military and war veterans. The war economy has also created a new set of beneficiaries who will stand to lose if military industry becomes a lesser priority. In addition, freezing the war would also unfreeze serious underlying political, economic, and social problems in Russia that have been suppressed since February 2022.

However, stopping the war would also bring clear advantages for the Kremlin. It would allow the armed forces to rebuild and prepare for a possible next phase of the war. It would probably also lead to the lifting of some damaging Western sanctions and allow greater opportunities to exploit divisions in the West. Finally, if a peace agreement brought about the end of martial law in Ukraine, fresh elections might result in Zelensky leaving office and allow Putin to claim for internal purposes that Ukraine’s leadership had been successfully “denazified.”

Yet the prize on offer by continuing the war is much more tempting: the defeat of Ukraine would not just dramatically roll back Western influence in international affairs; it would also give the Putin regime a new lease of life at home and buy it time to prepare for its leader’s succession.

However, resisting the Trump Administration’s efforts to impose peace would carry the substantial risk of an unpredictable response from Washington and further aggravation of relations with Western countries. Allies who have helped Russia to mitigate the effects of sanctions might no longer do so if their support were to become a liability to themselves. Further economic deterioration and the prospect of Russia losing technological ground at an accelerating pace would inflict serious long-term damage on the country.

This report examines overall Russia’s capacity to continue fighting the war and the factors shaping the Kremlin’s risk/benefit calculation at this critical moment. It does not aim to predict the path that Putin will take in negotiations with Trump but seeks to understand the main factors which will influence his decision-making.

The War Economy

The idea that the Russian economy would limit the ability of Putin’s regime to wage a war in Ukraine has been substantially revised. Right at the start of the war in spring of 2022, and after the announcement of Western sanctions against Russia, the overriding expectation was that the economy would be unable to cope with the pressure and risked collapse. At the end of the third year of the war the general consensus is that Russia has successfully adapted to sanctions, and has coped with the burden on the budget in the short to medium term by concentrating on military expenditure.

An Unstable Equilibrium

A recent report by Russian opposition economists notes:

“The hope evaporated long ago that the war and sanctions would destroy the Russian economy and stop Putin in his tracks. The price for keeping the economy sustainable has been paid by halting development, most of all in technology. But this will be felt much later. For now, the economy is set up in such a way as to allow the Kremlin to satisfy its military needs for years to come. What’s worst of all is that the economy has successfully been switched over to a war-fighting economy, and even an end to the war would strengthen Russian militarism. The world must be prepared for a long confrontation with an aggressive Russia with Putin in charge.”

The macroeconomic background looks challenging but not threatening for the Kremlin. Resources should last for another three to five years. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Kremlin is experiencing some economic hardship. This was illustrated, for example, in December 2024, when Putin addressed the Collegium of the Ministry of Defense. If previously he had given carte-blanche to the financing of the military, now he called for the military budget to be used prudently:

“We are spending 6.3 percent of GNP on the military, on raising and strengthening our defensive capacity… This is a large sum of money, and we must use it very rationally; very rationally ensuring that first and foremost the social needs of our military personnel are met, and that the military-industrial complex is operating effectively.”

In addition, the government has begun to cut back on certain ambitious and widely proclaimed geostrategic budget programs, such as the construction of nuclear-powered ice-breakers and the strengthening of rail links to the Pacific Ocean. Experts consider that forward planning for the Russian economy now looks no more than three years ahead.

In 2022, the Russian budget was boosted by $170 billion thanks to the following:

- High energy prices: Urals oil was selling for $75–80 a barrel, and prices also rose for the gas which Gazprom could sell on spot markets

- Restrictions on capital outflow: A ban on exporting capital from Russia

- A sharp decline in imports: The balance of trade stood at a record $225 billion.

However, this trend is now over, and problems are mounting in the economy. Russian business has an increasingly negative outlook. Although the Central Bank’s consolidated business climate indicator rose in the first half of 2024, it has since fallen. According to a survey of employers carried out by the recruitment site hh.ru, 26 percent of Russian businesses see a negative growth scenario for their companies in 2025. This is two and half times greater than it was in 2023.

The Illusion of Import Substitution and Sanctions

In the real economy, problems will always occur which cannot be solved simply by an injection of cash. An example is what happened at the Klimov cartridge plant near Moscow last year. An accident in the plant’s boiler room when the temperature outside was minus 4 Fahrenheit left more than 20,000 people without heating.

As well as such emergencies, there are cases where the gradual effect of Western sanctions is being felt. One example is air travel. In 2022, 95 percent of Russian passenger aircraft came from foreign companies. The ban on providing spare parts for these aircraft (to say nothing of new airplanes) saw the fleet of foreign aircraft being cannibalized. As a result, the number of foreign aircraft in service is thought to have been reduced by 10–15 percent. Foreign aircraft carried 89 percent of passengers on Russian flights in 2024, while the recovery growth of passenger journeys increased by 5.6 percent. But experts consider that this sector reached its limit last year. This figure is expected to decrease in the future, because there will be a shortage of aircraft.

The Russian authorities calculated that over the course of three to five years the country’s aircraft industry would be able to replace the Boeing and Airbus airplanes which had gone out of service, but this has not happened. There are still no entirely Russian aircraft being made. Programs to produce civil airliners, such as the “Superjets,” the Il-114-300, the Tu-214 and the MS-21, have not been fulfilled, mainly because of problems with domestically-produced engines.

Notably, the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC), which is responsible for the construction of all the above-named aircraft, has been radically switched to building military aircraft during the war. According to figures released in December 2023, OAK factories increased their production by 30 percent over the course of the year.

An example in a different sector which appears—at first glance—to be a success story is the Novatek project. This is the Arctic LNG-2 liquefied gas plant, for which 21 ice-class tankers were chartered at the Zvezda shipyard in the Far East and in South Korea. The raw material has been extracted, liquefaction capacities are in operation, but transportation of the finished product is blocked. Gas carriers were built in South Korea, but sanctions are preventing their handover to Novatek. And the construction of gas carriers at the Zvezda shipyard is delayed because of a shortage of qualified workers, parts and metal. In this situation, the Kremlin has to consider exotic projects, such as using Novatek’s gas to supply the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Labor Shortage

The main issue affecting the Russian economy is the shortage of labor. The war has intensified the demographic problem, not so much because of those who have been taken out of the workforce to go and fight at the front, but in particular because of the 500,000 or so skilled workers who have left the country. The military-industrial complex (MIC) is working on a three-shift system around the clock. It is desperately in need of workers, and it can pay them ever higher wages. But it is taking the best-qualified specialists away from the civilian economy. The increase in wages is even outpacing inflation; not to mention the growth in productivity, which is estimated to be 3.3 percent per year.

Record low unemployment is not an achievement, but a problem which it is impossible to solve. Even experts who are close to the authorities reckon that the workforce is lacking 1.6 to 2 million people. And there is a shortage of some 600,000 engineers.

A Two-Speed Economy

The encouraging picture of economic growth has come about largely thanks to the “war economy”: the production of “weapons of destruction” has been added to the production of “weapons of labor.”

In 2024, the Russian economy showed enviable rates of growth. Provisional figures suggest that GDP reached 4 percent, up from 3.6 percent in 2023. But looking at each quarter in turn, it is clear that growth was slowing as the year went on. In addition, the workload placed on enterprises, the demand for labor, inflation, and the interest rates on loans—all remained extremely high. Slowing growth combined with high demand is a sign of looming stagflation.

Figures from Rosstat show that genuine growth in the manufacturing industry is taking place only in those sectors connected to military production. In other sectors, growth is, at best, stagnant—and more likely falling.

This tendency is clearly visible in three sectors which are fundamentally “military”: metal products, computers and optics, and transport engineering. Even in sectors which are predominantly civilian (such as the textile industry), growth is largely the result of orders from the military. Such a situation is unstable, and leads to an increase in economic and social tension.

Zero growth, or producing fewer consumer goods while the people’s income is increasing, is a recipe for high inflation. A high discount rate and subsidized credits for the MIC enable the flow of resources from the civilian sector to the military, and risk bleeding dry an economy which was already weak. As a result, private business—the market part of the Russian economy—is under threat, the very sector that helped the economy adapt to new conditions in 2022.

Military Expenditure

Actual military production makes up at least eight percent of the Russian economy. However, if services, transport, material and technical support are added, then the figure is double that, if not more.

Since the start of the war, the workforce in the MIC has increased by around 700,000, to 3.8 million. That is just under half the number of those working in manufacturing industries. According to the Minister of Industry and Trade, Anton Alikhanov, some 900 civilian enterprises are engaged in producing goods for military or dual military-civilian use; and that does not include companies which supply these enterprises.

State orders for the military exceeded four billion rubles ($41 million) in 2023, the majority of which went on the production of armaments and technology. Of this sum, 60–70 percent is spent on actually making the end product; the rest goes on modernizing and servicing the production equipment.

Arms exports have more than halved since the start of the war. They were running at $13–15 billion a year (according to the current exchange rate, this is 1.3–1.5 trillion rubles). Sergei Chemezov, CEO of Rostec, has estimated that arms exports in 2023 were down to $6 billion.

It is fair to assume that the multiplier effect of military expenditure in related industries, such as metallurgy, machine-building, electronics, the chemical industry and scientific research, adds 0.5–1 percent to GDP.

In total, arms production adds around 4–5 percent to Russia’s GDP, or 6–8 trillion rubles ($6.03–8.06 billion) annually. But this is merely statistical growth without any real development.

The Regions

The war economy and the sanctions have impacted the major cities and the regions in different ways. The post-industrial economy, primarily concentrated in large cities, has suffered, while previously depressed regions have benefited from increased military production and cash inflows driven by payments to soldiers fighting in Ukraine. These included payments to wounded servicemen and families of those killed in action.

The regional contrast has notably changed with this decline in the major cities and the economic uplift in the provinces, and it has raised the average level of people’s prosperity. Up until July 2024, when the program of privileged mortgages for newly constructed homes was ended, the major centers of the MIC had witnessed a construction boom.

According to Rosstat data, industrial production in half of the country’s regions fell in 2022, but by 2023 the majority of regions had managed to halt this decline. The exceptions to this were the North-West and the Far East, where the decline only worsened. In 2024, the Siberian regions could be added to this list. The regions where growth was most keenly felt were those where the MIC is based (Central Russia, the Volga region and parts of the Urals region), and also Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Particularly acute problems in certain regions tend to be linked to the local situation. These include the regions bordering on Ukraine—Belgorod, Bryansk and Kursk Regions—and also occupied Crimea. A full-scale military operation is going on in Kursk Region, and Crimea is subjected to regular missile and drone attacks.

In January 2025, the government passed the new Spatial Development Strategy to the year 2030, classing certain geostrategic territories as “priority.” These include the six annexed regions of Ukraine, the entire Far East, the whole of the Northern Caucasus, the Arctic zone, and municipalities which border on “unfriendly” foreign states.

Outlook

The Russian economy is neither as strong as some experts claim, nor is it as weak as others would suggest. It is certainly far from being as stable as it was in peacetime before the application of sanctions, nor is it as maneuverable or adaptable as it was in 2022. There are clear signs of decline, but in the next one or two years these economic problems will not prevent the regime from continuing the war.

For now, the Kremlin is managing to cope with three tasks at once: the financing of the war, maintaining living standards, and supporting economic growth. In fighting the war, the Kremlin has a reliable macroeconomic backdrop, even though problems are increasing: the structural imbalance is growing and future development is being blocked, partly as a result of Western sanctions.

Serious failures may occur in separate sectors of the economy, but there are no signs that they will affect the regime’s ability to continue the full-scale war in 2025 or 2026.

Russia’s Military-Industrial Complex

The decision to significantly increase military expenditure was taken back in 2011. When sanctions were imposed on Russia following its seizure of Crimea in 2014, the military-industrial complex (MIC) adapted quickly and began a program of import replacement. In any case, the MIC was always far less dependent on imports than the civilian sector. The war in Ukraine today is similar to the wars of the first half of the twentieth century, and for this Russia has the material and technical resources to meet its requirements.

For now, the Russian MIC is working flat out, and meeting the needs of the army in the field, even if this means restoring huge amounts of military equipment which has been in store since Soviet times. North Korea and Iran, regimes friendly to the Kremlin, are extra sources of weaponry and ammunition, and Russia is also using for its own needs weaponry which until recently was marked for export. While arms exports contracted significantly after the start of the full-scale invasion, it still exported to 12 countries in 2023.

Production in the MIC has probably reached its peak. Everything which could be done to develop it further has already been put in place. From where it is now, production can only decline. Without the necessary imported spare parts, aging high-precision machine tools are ceasing to work, and the workforce is growing older and not being replaced.

The problem of machine tools can be solved, including by switching production to older energy- and material-intensive technologies. However, the workforce issue is much more difficult to deal with. There is nowhere for workers to receive the necessary training; it is impossible to increase output using the outdated technology (and not only the machine tools), and, as a result, the capabilities of the MIC are decreasing. The MIC has used up all possible resources for extensive growth. It is working to its maximum, and there will be no growth either in quantity or quality.

On the one hand, the range of available weaponry is becoming more narrow. On the other, the weapons they have are being modified in an ad-hoc manner and further developed on the battlefield. The reality of the situation means that in place of the high-tech, modern T-90 tank, old Soviet tanks are being taken out of storage and modernized, even ones as old as the T-55. They are being fitted with new guidance systems and anti-drone defenses.

Production is inevitably becoming simpler, thanks both to the limited access to Western parts and technology, and because the most modern equipment is being damaged beyond repair.

Production capacity is being destroyed in Crimea and in the Russian regions which border on Ukraine, because production facilities are being targeted by Ukrainian drones and missiles. At the same time, facilities far from the frontline are being expanded, and more industry is being shifted to the east. For example, major ship-building yards are under construction in the Primorsky region in the Far East. This indicates that the Kremlin has plans for a long-term confrontation with the West.

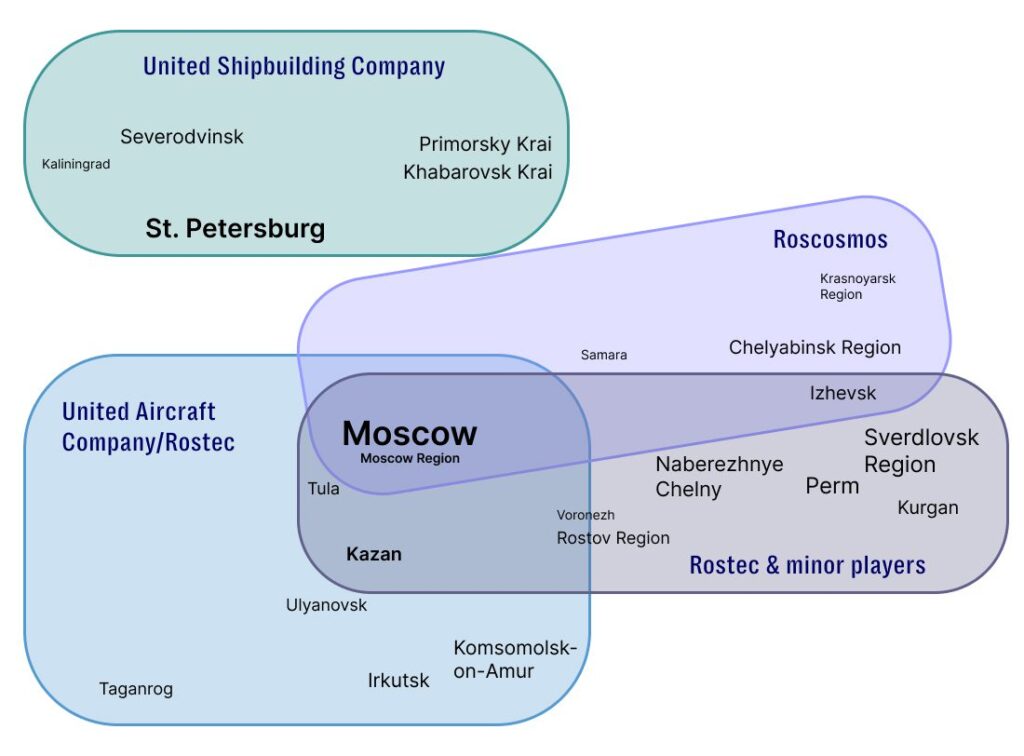

Fig. 1. Military-Industrial Complex: Regional Structures

Adapting Weaponry

With sophisticated high-tech weaponry being destroyed—there are limited reserves of such weapons, and their production is expensive and difficult to scale up—constant improvements are being made to the manufactured products, adapting them to the demands of the war in Ukraine and the changing military situation. Two examples of this are fibre-optic drones and grilles which have been fitted to tanks.

Drones

The war in Ukraine has demonstrated the effectiveness of unmanned aerial vehicles (drones). The Russian army started by using Iranian-made Shahed-136 drones, but swiftly began to produce their own drones at various facilities.

In December 2022, the Russian government approved the “Unmanned Aviation Systems” project, as one of the national priorities of Russia’s state strategy for developing dual-use technology. Over 100 billion rubles ($1.02 billion) were allocated to the project for 2023–2025, to support research and experimental construction work and production. Andrei Belousov was put in charge of the project. At that time he was first deputy chairman of the government; he is now Minister of Defense.

On September 19, 2024, the feast day of the warrior saint Archangel Michael, Vladimir Putin conducted a video call with the military-industrial commission. The call covered the development of special purpose unmanned aviation systems. Putin announced that in 2023 the armed forces had been provided with some 140,000 unmanned flying vehicles of various types, and that the plan was to increase their production by almost ten times in 2024. He emphasized that, as well as the large companies involved in the project, small and medium enterprises—the so-called “people’s military-industrial complex”—would also play a part in the mass production of these drones.

Putin declared that an extensive network was being created of special research and production centers for the planning, trialling and production of drones. This was an important point which illustrated the scale of this project. It is intended to create 48 such centers in various regions of the country by 2030.

Technical improvements in drone design, such as fibre-optic drones that are immune to electronic warfare, are often made on the battlefield, and subsequently refined and copied in factories far from the frontline.

Another example of an improvement carried out by skilled workers at the front was the use of grilles: metal gratings, nets or carcasses placed on the turret of a tank or even over the whole vehicle, to defend against kamikaze-drones or air-dropped ammunition. At first, these grilles were fitted by individual regions or corporations which were supervising specific army units; then they began to be fitted at repair facilities.

Air-Launched Guided Bombs

Smart guided bombs are fitted with a simple control and guidance system. They have a much higher filling factor than air-to-surface missiles—the ratio of the mass of explosive to the total mass of the bomb. They are actively used for the destruction of strategic targets, arms depots, command posts and strengthened positions. Since 2022, enterprises of the Tactical Missile Weapons corporation, and factories associated with it, have greatly increased their production of these weapons.

These smart bombs cost three to six million rubles, up to 15–20 million ($30,700–61,300; $153,000–204,300 approx.), which is significantly higher than ordinary bombs, but much lower than the cost of guided missiles. Mass production brings the cost down, and the increase in production since 2022 has also meant that they are now cheaper to make.

The Organization and Management of the Military-Industrial Complex

At the start of the war the development of the MIC lay with the following organisations: the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the government, the Military-Industrial Commission, and the Security Council. The actual production was handled by enterprises in three major state corporations (Rostec, Roscosmos, and Rosatom); a few independent companies (Almaz-Antey, Tactical Missile Weapons and the Space Rocket Corporation “Energiya”); and also a large number of relatively small private enterprises.

Since then, the MIC has been reorganized twice. First, in the second half of 2022, when it was clear that the intended blitzkrieg had not worked and it would be necessary to prepare for a long drawn-out war; and then again in mid-2024, when the Kremlin decided to make the management of the MIC more efficient for the long-term. A large number of personnel and institutional changes were made.

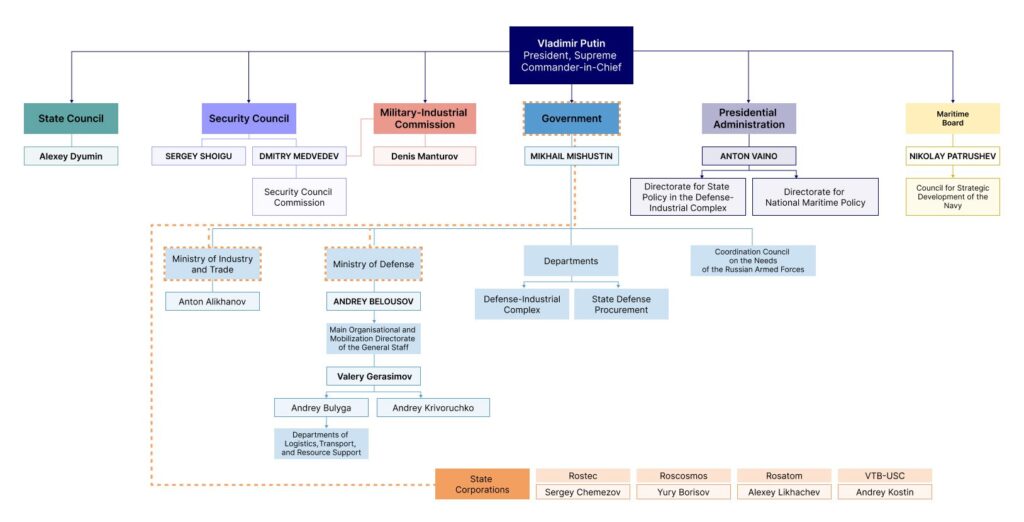

Fig. 2. Military-Industrial Complex: Management Structure

The first reorganization saw a reshuffle of personnel. Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov was appointed Director General of Roscosmos, and given the task of vastly increasing the number of satellite launches. In July 2022, Denis Manturov, the Minister of Industry and Trade, was promoted to Deputy Chairman of the government. In October that year, a coordinating council was formed within the government to deal with the army’s needs. The Military-Industrial commission was reorganized in December.

The second reorganization aimed to centralize the structure and place it under Putin’s personal control. Andrei Belousov replaced Sergei Shoigu as Defense Minister. Next, a MIC headquarters was created in the management group of the Ministry of Defense within the Presidential Administration, with Putin’s aides, Alexei Dyumin and Nikolai Patrushev, as members. The apparatus of the Security Council under its new secretary, Shoigu, was downgraded; but the MIC component within it was strengthened. There was also a radical reshuffle of personnel in the management of the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) and the organizations associated with it. A similar reshuffle had taken place a year earlier in the United Shipbuilding Corporation (USC).

The first changes made to the MIC system of management were designed to address the problems encountered with coordination and the operations of the structures responsible for supplying the army, both among themselves and with the army itself. The second set of changes, in 2024, showed that the Kremlin was determined to strengthen the MIC, to deal with serious failures in production and the poor way these had been handled, and try once more to improve its management.

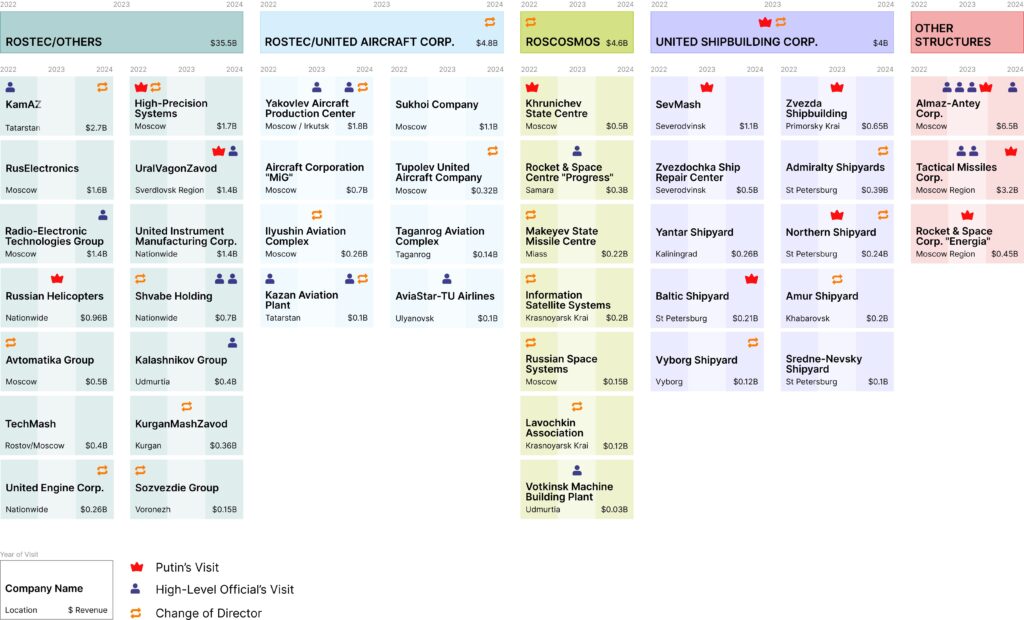

Fig. 3. Military-Industrial Complex: General Structure

Outlook

As two leading U.S. analysts have noted: “Russian industry has not been able to significantly scale the production of major platforms and weapons systems. Labour and machine tools remain major constraints because of Western sanctions and export controls. Russia has still been able to significantly increase the production of missiles, precision-guided weapons, drones, and artillery munitions, and it has set up an effective repair and refurbishment pipeline for existing equipment. But it is also drawing from ageing stocks that it inherited from the Soviet Union for much of its land force equipment. Thus, as it expands its forces and replaces losses, it is depleting its resources.”

Nevertheless, the massive and diversified capabilities of Russia’s MIC, combined with the resources at its disposal, are sufficient to support the war in Ukraine at its present level of intensity at least for another 12 to 24 months assuming that equipment stocks in storage are not exhausted. The success of the drone production program illustrates that the MIC can be flexible and also change course when developments on the battlefield demand it.

The Army

After a very poorly planned and conducted invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and a particularly challenging first year in combat, the Russian army regrouped and rediscovered military doctrine and tactics. This allowed it to dig in and repel the Ukrainian counteroffensive of 2023. It regained the tactical initiative in 2024 despite very high human and equipment costs. By February 2025, it had failed to turn increasing tactical successes on the front line into deep operations to unlock Ukraine’s defenses.

Since 2022, it is clear that Russia has improved its force structures, logistics, operations and supply of equipment, successfully integrating old Soviet era equipment with newer technologies.

There has also been a marked improvement in tactical precision strikes by reducing the time between finding a target and attacking it. Rapid adoption of different unmanned air systems has led to the integration of large numbers of drones and helped make Russian kill chains more efficient. Drone lethality and success rates have also increased as Russian operators have become more efficient.

Russia’s electronic warfare has also improved, countering the advantage that Ukrainian drone operators enjoyed at the start of the war, and complicating use of Western-supplied weapons dependent on GPS.

The targeting process for attacking Ukrainian critical infrastructure has become more effective with much greater focus on higher impact targets than in the early stage of the war. The result has been the destruction of 50 percent of Ukraine’s peak power generation capacity.

The ability to learn from mistakes and improve performance is a key strength. Nevertheless, over three years, the army has conspicuously failed to turn its two-fold superiority in manpower and equipment to decisive advantage.

Since the ground forces have done most of the fighting, much of the capability of the rest of the Russian armed forces remains unaffected by the war. Apart from the Black Sea Fleet (BSF), the Navy remains untouched in the Barents, Arctic, and Pacific. Russia’s nuclear deterrent triad is also intact, with further test firings taking place.

Although the Aerospace Forces have not achieved air superiority over Ukraine, this is not a task for which they were designed. They still have the capacity to present a significant challenge for any conventional aggressor, although they have struggled to deal with the Ukrainian drone and missile threat in Crimea. Key airborne early warning and command and control aircraft shot down during the war have not been replaced.

Despite the improvement in Russia’s tactics, the armed forces still have several weaknesses that for now would severely limit the capacity of the Russian army to fight a better equipped and trained force than the Ukrainian army. They can be summarized as follows:

- Command and control. The army remains heavily centralized with planning conducted in Moscow and delegated for execution to the fronts. Trust between various echelons and services is weak, leading to a lack of unity of effort and competition for resources. There is also a lack of challenge, a tendency to “group think,” and to tell superiors what they want to hear. Those willing to speak out have usually been fired.

- Culture. Corruption remains endemic as does a disregard by officers for the lives and well-being of their subordinates. Tactical doctrine is inconsistently applied, increasing loss of life.

- Intelligence. The armed forces have consistently shown a lack of understanding of their adversary, overconfidence in the attack, and a tendency to underestimate Ukrainians. As shown in 2022 and again in 2024, strategic military intelligence on Ukraine is weak, leading to surprise at Kharkiv, Kherson, and Kursk.

Manpower

Much of the Russian professional army of early 2022 was destroyed in the first nine months of the war, with heavy casualties among junior and non-commissioned officers. As the army shifted to improvising and then using a follow-on force of older, inexperienced and badly trained volunteers for attritional frontal assaults, its overall quality predictably fell.

Since mid-2023, the army has shown the ability to conduct more sophisticated tactical maneuvers that have led to the capture of several well-defended small towns and villages in Donbas. New mid- and senior-level commanders have come to the fore after performing well at lower levels. At the heart of the officer corps there is now a strong cadre with combat experience and the skills to cope with the specific demands of this war, including adapting to the use of new types of weaponry such as drones.

However, officer losses have been high. In 32 months of fighting, an estimated 25,000 to 27,000 officers have been killed or seriously injured. Military academies turn out 5,000 to 6,000 officers per year for the ground forces (an estimate by a Russian military analyst consulted for this paper), i.e. well below the attrition rate of 9,000 to 10,000 per year. To cover the shortfall, the army is calling up reserve officers, promoting non-commissioned officers after short training courses and taking recently graduated officers from academies. This response is creating divisions within the officer corps between those with the necessary experience and skills and those without.

Manning the army poses challenges in view of the continuing very high casualty rates (around 30,000 per month) that were roughly matched by the recruitment of contract soldiers up to late 2024 when the numbers of recruits fell to around 20,000 a month. In autumn 2022, operational losses of 40,000 to 45,000 (around 20–25 percent of the invasion force) led to 300,000 soldiers being mobilized and sent to Ukraine.

In September 2024, Putin ordered an increase of active service personnel to 1.5 million in part also to man expanded forces in the northwest of Russia in response to Finland and Sweden joining NATO. The General Staff wants to mobilize 300,000 to 400,000 soldiers to reach the 1.5 million goal. However, the Kremlin is nervous about further mobilization because of a potentially negative reaction from society. The previous partial mobilization led to around a million Russians leaving the country although roughly 10–15 percent later returned because of difficulties settling abroad.

It is becoming more expensive for the Russian authorities to attract contract soldiers to fight in Ukraine. While the average pay for a private soldier is equivalent to $2,000, the current minimum payment to enlist is around $8,000 per soldier, and on average $15,000 paid in the main from the regional budget where the soldier signs on, with a top up from the federal budget.

Fig. 4. Payments to Military Personnel for Signing a Contract in 2024

Inability to Conduct Large-Scale Combined Arms Operations

Training for large-scale combined arms operations has also ceased or been curtailed. Restoring the capacity for conducting operations on this scale, an art that the Red Army perfected during the Second World War, will probably take 7–10 years.

This will require reconstitution of men, equipment, force structure changes as well as realistic training, efforts that will need to be balanced with available government funding and demography. It may also prove hard, once the war in Ukraine is over, to retain experienced army personnel to carry out this task.

Equipment

Replacement of armor destroyed since the start of the war could become a serious challenge in 2025. In the case of tanks, the military industry has supplied around 20–35 percent of the estimated 3,400 units that have required replacement. The rest have come from older models stockpiled in the 1990s. Over half of these stocks, mainly tanks from the 1960s, have been used up. The army could face equipment shortages if combat continues at current levels of intensity and industry cannot ramp up production. Further large-scale mobilization would also pose challenges because of lack of serviceable equipment.

The army faces problems with worn out artillery barrels (requiring one or two years to replace in full). Stockpiles of long-range conventional missiles have reduced, decreasing their deterrent effect against NATO, and increasing the importance of the nuclear triad (missiles launched from land, sea, and air). “Hypersonic” ballistic missiles have not proven to be the game changer predicted by Putin. It is not clear that the Oreshnik missile tested against one Ukrainian target so far has anything more than PR value.

Dependency on Foreign Suppliers

Supplies from China, Iran, and North Korea have helped Russia to mitigate the impact of sanctions and domestic war pressures. The three countries have supplied Russia with much needed dual-use items, arms, and spare parts. While these goods have generally been of lower quality than their Western alternatives, they have allowed Russia to sustain the war and contributed to the Russian army’s battlefield progress in 2024. Without this support, Russia would be unable to maintain its tempo or replenish losses as quickly. If the war continues further into 2025 at current rates of intensity, Russia may require other countries to transfer equipment.

Challenges of Rebuilding

For now, the army is managing to refurbish older equipment at sufficient rates and recruit enough volunteers to continue to fight in Ukraine. The economy, although under obvious strain, is providing enough resources to fund the war. The army can continue fighting for another 1–1.5 years at current rates of attrition.

Russia faces multiple financial and demographic challenges that constrain how and how far it can replenish its armed forces qualitatively and quantitatively by 2030, while still sustaining its war in Ukraine. Clearly, the longer it continues to fight in Ukraine, the longer this rebuilding process will last and the more costly it will be.

It will take four to five years to reach the target of 1.5 million active servicemen, but it is highly unlikely that the army will be able to conduct large-scale, combined arms operations without a long period (possibly 7–10 years) of reconsolidation.

Rebuilding the officer corps and improving its skills, particularly at junior officer level will place significant strain on the military education system. This is likely to take two or three years.

Strategic Setbacks

Ukraine’s Western allies have forced it to fight with one arm behind its back for fear of further escalating the war. The restrictions imposed on targeting Russian forces have gradually been rolled back, but not in time to stop the Russian army increasing its pace of advance along much of the front line. For the first six months of 2024, U.S. military aid was suspended because of lack of Congressional approval. This delay cost Ukraine dearly. The prospect of a complete cessation of aid once the “surge” of weapons deliveries from the outgoing administration ends could make it very hard for the Ukrainian army to hold the front line. Nevertheless, the biggest problem for Kyiv is the lack of soldiers, particularly well-trained units.

For now, the Russian army will continue to grind its way forward in Donbas with the increased possibility that it can achieve an operational breakthrough, particularly if it opens a new front in southern Ukraine.

The longer Putin can continue fighting ahead of negotiations, the greater the likelihood that he will gain greater territory to strengthen his hand in talks on the security arrangements that will be at the core of any peace deal.

Table 1. The Russian Armed Forces in 2022 and 2025: Comparison

| 2022 | 2025 | |

| Size and structure | The invasion army: 150,000 to 200,000 strong, made up from the armed forces and Rosgvardiya. | At the current time on the frontline: according to official statistics, 600,000 to 700,000; expert assessment, 400,000 to 500,000.Losses:Dead: known by name, 90,000; actual number probably close to 200,000. |

| “Militia” occupying parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, which were already in a state of war:30,000 to 40,000 at the start, rose to 100,000 when the territories were “annexed” to Russia. | These “militias” were incorporated into the armed forces. | |

| Experience and length of service | Professional units—only trained contract soldiers. Intelligence assessments indicated that there would be no need for mobilization. | Former soldiers, called up because they had two years’ military experience; new contract soldiers, organized in territorial units. |

| Tactics and practice | A poorly planned invasion, ignoring the possibility of prolonged, organized resistance; with weak intelligence, inadequate defensive cover, and severe logistical disruptions. | Expansion of units and addition of assault detachments. Rapid adaptation of drones and electronic warfare. Employment of small infantry and mechanized groupings. |

| Internal organisation | Groups of forces, West, Center, South, East: large formations with poor coordination between commanders, and chaos caused by different centers taking their own decisions. Basic unit: battalion-tactical group. | Groups of forces, West, Center, South, East, North, Dnepr. Strict centralization at the higher command level, decentralized at the lower level.Organized as divisions–regiments–battalions, but operating mostly in smaller detachments. |

| Armaments and equipment | Modernized Soviet equipment with new long-range precision strike systems. Base tank—T-72B3, IFV: BMP-2, BTR-82A, artillery Msta-S. | Legacy Soviet weaponry adapted for this war. Rapid development of unmanned aerial systems and electronic warfare; adoption of commercial technologies for the needs of the war; improved precision guided weapons such as air-launched guided bombs. |

| Feedback | The replacement of military equipment which has been destroyed or lost without due consideration. | The operational vulnerability analysis (“the people’s military-industrial complex”) puts forward practical suggestions which may be adopted further up the chain of command. One example was fitting grilles on armored vehicles. |

| Junior officers and their replacements | Career officers with the appropriate training, each in command of around 17 soldiers. | The attrition of officers has been compensated for partly by using graduates of military schools and mobilized reservists with prior experience, and partly by those trained directly at the frontline with just two to six weeks of preparation at best among base-level contract soldiers, as it was during World War II. |

| Senior officers | Generals who had experience of the Syria campaign; officers with limited fighting experience. | Promotion to senior ranks of middle-ranking officers who have performed well in battle; rotating generals based on performance. |

| Morale | Overconfidence rapidly paves the way to discouragement; lack of preparation for war, or understanding of orders and objectives; low trust in officers and no sense of mission. | High rates of pay have made the war well-paid, if risky, work. Anger towards “the enemy.” Burnout of mobilized soldiers. Hazing of junior soldiers (Russian: dedovshchina). |

Source: Compiled by the authors of the report with the participation of Russian and foreign experts.

Outlook

The Russian army has become a properly functioning army. Unity of command has clarified tasks and responsibilities; horizontal links have markedly improved flexibility and effectiveness in carrying out military functions; new weaponry and tactical ideas have been swiftly adopted in Ukraine.

A ceasefire would allow the Russian army to replace its losses of personnel, weapons and ammunition; and the experience of the Ukrainian campaign means that it will be a better prepared and more capable force if required to continue fighting.

Demography and Society

Russia has an ageing population, and is declining demographically. The population has not grown since the mid-1990s, due to a natural fall in the birthrate and a reduction in migration. Three-quarters of the country’s regions are experiencing depopulation. This is especially felt in the Far East.

Demographic and migration policy has never been seriously addressed by the Putin regime. Putin’s first initiative in this area was the idea of “maternal capital”: trying to increase the birthrate using money as an incentive. In 2007, it was announced that the government would pay a significant sum of money for the birth of a second child. In 2020, this was extended to the birth of a first child. As of February 2025, the amount paid for a first child is 690,000 rubles ($7,050). For the second child a family receives approximately one third of this sum.

Encouraged by an upturn in the birthrate, in 2012 Putin tasked the government with increasing the country’s population to 154 million by the year 2050. Unfortunately, the policy of “buying births” has not paid off. There was a short-term effect. Thanks to the money being paid out and a largely positive situation in the country, births of first and second children rose. However, this did not alter the reduction in the overall fertility rate, which once again started to fall. The 2015 rate of 1.78 births per woman had fallen to 1.41 by 2023, which is one and a half times lower than the rate needed simply to keep the size of the population stable. Rosstat forecasts that in 2024 the rate will have fallen to 1.32.

Migration policy is controlled by the police. Anti-immigration laws have become significantly tougher since the start of the war in Ukraine, and especially after the terrorist action carried out on the outskirts of Moscow in March 2024 by Tajik laborers in the name of Islamic State. This action, and the way it was portrayed in the Russian media, led to a sharp rise in xenophobia, to which the authorities responded. As a result, the situation for immigrants became decidedly harsher.

According to UN figures, in 2020 there were 11.6 million international immigrants in Russia: just over eight percent of the population. This means that Russia had the third largest number of immigrants in the world, after the U.S. and Germany. The Russian Interior Ministry’s possibly underestimated figures said that on October 1, 2023 there were over 6.5 million foreigners in the country, of whom 740,000 were there illegally. Expert analysis suggests that up to 600,000 people from Central Asia (who make up 90 percent of the foreign labor force) left Russia in the course of 2024. This was due to pressure from the authorities and the unstable ruble.

The working-age population in Russia is currently some 84–85 million people, which represents around 59 percent of the population. In 2024, about 74 million people were in work in Russia, of whom 12 million were self-employed.

Around 700,000 to one million people are lost from the working-age population each year, which exceeds the natural decline in the population. The rise in the pensionable age in 2018 delayed by five years the exodus of working-age people, and is expected to add around five million people to the numbers working up to the year 2030, which should partly compensate for the natural population decline.

The official figure for unemployment in Russia in December 2024 was a record low of 2.3 percent, which illustrates the shortage of labor. According to data from the Bank of Russia, 73 percent of enterprises are suffering a shortfall in personnel.

Which sectors are most hit by the serious shortage of labor?

- Construction, causing delays in infrastructure projects

- Industry, including the MIC, which is taking highly-qualified personnel from civilian enterprises

- Transport, where the shortage of the workforce is keenly felt, e.g., in railway teams moving goods

- Agriculture, which is facing a serious lack of seasonal labor for gathering the harvest.

There are not even enough couriers. According to the vacancies aggregator website, more than 90 percent of companies are short of staff.

Ever since the Second World War, each successive generation has had a smaller population, which leads to a variety of social problems. A relatively prolific generation of those born in the 1970s is now moving into the older age group, beginning to leave the working-age population and the labor market. Overall, the population is falling, and the older population is increasing ever faster. Figures from Rosstat show that in 2023, 30 percent of the workforce was over the age of 50. The average age of the working population that year was 42.1 years.

According to the Ministry of Economic Development, the economy will need an extra 2.3 million workers by the year 2030. Half of these will come from internal resources, due to the cumulative effect of the pension reform and younger people coming into the workforce. The other half will come from increased productivity and more active involvement in the labor market by students and other citizens not currently involved in employment, as well as immigrants.

It appears that the Ministry of Economic Development is confusing what is desirable with what is actually happening. Any significant increase in labor productivity is limited by the impossibility of modernizing production due to Western sanctions. Enterprises must therefore expand while accepting a reduction in the quality of the workforce, by:

- Attracting students

- Extending the hours of the working week

- Introducing a lump sum payment for pensioners who are ready to return to work

- Compensating workers in areas which are most in demand by meeting their housing costs.

According to Rosstat’s figures, in 2023 the actual hours worked by each employee per week was 38.2. This is the highest rate in the last five years.

The situation in the labor market is made more difficult by the Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia in 2022, where the majority of the population is elderly. This was not taken into account in Rosstat’s forecasts. The problem is exacerbated by the “military emigration” of qualified specialists and the exodus of men of working age to the war. Furthermore, the Ministry of Defense is particularly keen to attract those who work in areas where there is already a shortage, such as drivers, tractor drivers, mechanics, and so on.

In December 2024, the Ministry of Economic Development put forward a plan for easing the labor shortage by introducing a change to the Labor Code. It suggested raising the amount of overtime allowed to four hours per day and 240 hours per year (double the current maximum of 120 hours). Overtime would be paid at twice the normal rate.

The worsening labor force situation affects not only the civil sector but the MIC, too. Nine out of ten enterprises engaged in shipbuilding, which are mainly working on defense orders, have problems finding skilled workers and engineers. The greatest demand is for turners, milling machine operators and grinders. Welders, fitters and engineers are also in short supply.

Ever since the start of the pandemic the Russian labor market has experienced a huge number of vacancies. According to one expert on the labor market, this has already passed the record of seven percent. This is all-encompassing: there is no single sector, nor any professional group, where it has not been felt. A shrinking labor supply, record low unemployment, more vacancies than ever before, sharply accelerated turnover of workers, and long drawn-out stagnation in real pay—this unique combination of factors has meant that the labor market has had to start functioning in a new way.

The state of the labor market indicates that the MIC is currently working at maximum capacity and at the very edge of what is possible. Unless there is labor mobilization and wartime demands are imposed on workers, in current circumstances it is practically impossible to increase capacity or expand production.

Changes in Russian Society, Consequences of Demobilization

The war has shaken the structure of Russian society. In its third year, the number of those who have benefited from the war is the same as those who have lost out—around 20–25 percent of the population. In 2024, 22 percent of those questioned said that their material situation had improved, while 23 percent said that their situation had worsened. In Russia this is significant, because ever since 2015 the majority of respondents had been complaining that their situation had been getting worse. Of those polled, 35 percent said that they expected their lives to improve in 2025. In 2022, a mere 12 percent were so optimistic, while 54 percent expected their lives to get worse.

Among the losers now are the more modern, educated layers of society, as well as civil servants who are not involved in areas connected to the military—lower-ranking bureaucrats, municipal clerks, those working in the social sphere, local healthcare or education.

Among the winners are skilled and unskilled laborers, whose traditionally low wages have risen several fold because of the shortage of workers; those working in the military, police or other structures of power; and the technical intelligentsia whose work is connected to military industries.

The large sums of money being offered to those who sign up as contract soldiers and go off to the war (around one million people have already taken part in the war) have created such pressure on the labor market that even the police are suffering a shortage of manpower. The Interior Ministry is lacking 174,000 lower-ranking staff, which represents 19 percent of the total number. The Ministry is now ready to accept staff who have no formal education, which is a break from normal practice.

Devaluation of Social Capital

Emigration and repression have also weakened the educated and more progressive parts of society. Research into the wave of Russian emigration caused by the war shows that it is the more socially active people with progressive views who have left. They are better educated and more in demand as professionals than the average Russian.

However, repression and bans affect not only the educated and democratically-minded minority. Social cohesion as a whole is disappearing, as horizontal and vertical links in society are all being devalued. This is happening at all levels, from the erosion of regional elites with their integration into a single federal vertical of power, to the composition of individual social support networks used by ordinary Russians. Horizontal relations where people mutually assist one another are being replaced by relations based on patronage.

Banning and blocking Internet platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, and other repressive practices involving the Internet have led to the most varied social support networks either folding or going into hiding. This has happened from clubs based on particular interests; fan groups and unofficial sports organizations; to mutual support groups for mothers with small children.

For example, the largest mothers’ group, with about 150,000 members, was closed down by the organizers after the State Duma adopted a law in November 2024 banning “child-free propaganda.” As soon as the law was passed any public discussion linked to difficulties faced by mothers could be interpreted as spreading this banned “ideology,” leading to a fine of up to 400,000 rubles ($4,130) for an individual. Banning imaginary movements (for example, the non-existent “LGBT movement” and the spreading of information about changing sex are now banned in Russia) does not simply stop any discussion of socially important matters, but leads to the destruction of social capital and social connectivity.

Public opinion is now completely dominated by the ideology of conservatism and traditionalism, and is against inclusiveness. Those who have benefitted from these changes in everyday life which are linked to the war are exactly those parts of society who felt themselves “left behind” in the 2000s and 2010s. These two decades saw minimal modernization in society, of the kind that would promote greater well-being by showing people how to adapt to the capitalist way of life, and encouraging the spread of new technology and mass global culture.

Today, values such as showing initiative, self-realization and even the simplest form of being an individual under capitalism are losing their meaning. In every generation the highest demands are for stability (this has risen from 43 percent of the population in 2019 to 70 percent in 2024) and for people to adopt old habits and traditions (from 42 percent in 2019 to 64 percent in 2023).

Militarism is not so keenly felt among Russians: according to research by independent sociologists, the majority of those questioned would not support a second round of mobilization for the war (57 percent), but would support the authorities swiftly bringing military action to a close (78 percent). Almost three-quarters of those who took part in this poll (73 percent) believe that Russia is on the right path, but apparently support not so much the military intervention in Ukraine as the changes in society which have accompanied the war.

The presence, on the one hand, of a large number of beneficiaries of the war, and on the other, the devaluation of the social fabric, not only explains the lack of a prevailing anti-war sentiment in Russian society, but also makes any organized protests against the war highly unlikely in the next year or two. In present circumstances, it is also difficult to imagine that representatives of the elite will be called up to fight.

Prospects for Demobilization

Possibly because people are reasonably satisfied at the moment and the war has not yet brought serious economic problems, there has not been a rise in violent crime, despite warnings that this could happen. The long-term downward trend persists. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the number of registered murders in Russia fell by 9.8 percent in 2024 compared to 2023, while crimes involving grievous bodily harm decreased by 8.1 percent.

It is likely that the system of forming an army based on a well-paid military contract means that a large number of those who are inclined to violence are now on the frontline. This personal factor outweighs structural reasons, which frequently lead to a rise in crime in wartime. However, those who return from the frontline show a notable desire for violence: journalists have used open sources to demonstrate that there have already been about 500 cases of violent crime committed in Russia by those who have taken part in the “special military operation.”

The end of the war—or a significant drop in its intensity—will create serious problems for the Russian authorities. It is usually the case that there is an increase in crime after a war. This was seen in the 1980s and 1990s after the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. The mercenary nature of the Russian army which is fighting now means that this will be seen even more strongly than it was then.

Firstly, the post-war economic downturn in itself contributes to rising crime rates. Secondly, those returning from the war will not simply be demobilized soldiers but mercenaries accustomed to earning substantial sums for participating in combat, procuring their own weapons and equipment, and operating within a system where their relationships with commanders are based on economic incentives. They are likely to be far more capable and motivated to form organized criminal groups than veterans of other modern wars.

Moreover, the sharp rise in industrial wages is driven not only by a labor shortage, but also by massive government spending on the defense industry. If these expenditures are scaled back, a surge in unemployment or a significant decline in wages for unskilled labor can be expected, further exacerbating social tensions.

Finally, state propaganda portrays "special military operation” participants as heroes deserving of high status and influence in society. Local administrations reinforce this narrative, competing to provide veterans with various benefits and privileges. However, local communities are largely unwilling to recognize them in this way. As analyses of regional media and social media posts indicate, these veterans are often met with fear and distrust. There have been signs that returning soldiers frequently find themselves in conflict with relatives and acquaintances, while those who were wounded receive little support from their surroundings. Most crimes committed by returning combatants are linked to conflicts within their immediate circles and the manifestation of war trauma.

Outlook

In the event of the war pausing or ending and its participants returning home, it is reasonable to expect increased tension in society, outbreaks of violence, and possibly some disorganization among the authorities. Should this happen, the ability of the healthy part of society to organize itself has been severely damaged, to the point where it will be impossible in the near future for progressive forces to mobilize around democratic values. The only kind of mobilization we can expect will be that of socially conservative circles organizing right-wing vigilante groups.

Demographic problems and the fear of immigration mean that both the federal authorities and those at the local level will be tempted to encourage grassroots xenophobia, policies against inclusivity, and pressure on Russian parents to have more children. The older and less educated elements in society will support these policies much more actively than they will the regime’s imperialistic foreign policy.

In other words, the federal authorities may find that they are up against opponents who represent fundamental movements and organizations which are more in tune with the anti-modernist mood of society—the very mood which the authorities are now using to ensure the passive support of the majority.

We can also expect to see a growth in organized crime and the formation of paramilitary units under the auspices of local authorities and corporations (this is already happening in places). There will be conflicts both among these formations and between them and the law-enforcement agencies. The authorities will have to solve the problem of integrating some of these informal power structures into the political system and wiping out others by force. This could lead to the strengthening of the structures of power, and even greater repression and centralization of authority.

Table 2. Russian Society Before the War and the Pandemic and Now

| Before the war and COVID-19 | Today |

| Growth in using modern technology | Discrediting modern technology

This leads to bans, and the slowing down of development |

| Greater density and diversity of horizontal social links | Social atomization

Leading to horizontal links being replaced by hierarchical ones |

| Growth in the popularity of modern values (contrary to the policy dictated from above) | Modern values are discredited |

| Formation of a grassroots anti-modernization coalition and resentment (supported by the authorities) | The victory of the anti-modernization coalition (reflected in the redistribution of income and status) |

| Hardly noticeable mood of militarism | Passive support for the war |

| Demand for social progress and internal development is to the fore | Demand for social conservation rather than social development |

Source: Compiled by the authors of the report.

Elites

The concept of an elite is applied very cautiously to Putin’s authoritarian regime, based on a networked bureaucracy. This mafiosi-nomenklatura elite that subdivides into different groups has no free will. Consolidating themselves around Putin is not a question of an individual or collective choice; it is simply the way to survive.

Putin’s regime is more united now than it was before the war, thanks to strict control allied with internal repression; and, externally, the pressure of Western sanctions. Regardless of their initial attitude to the war, Putin’s elites have no choice: their personal survival is now hostage to the survival of the regime. And over the course of three years of harsh confrontation between Russia and the West, they have imbibed anti-Western sentiments, even if they did not have them at the start.

Starting in 2014 and especially since 2022, the elite’s dependence on Putin as their leader has increased, just as the independence of the individuals in the group has declined. Earlier descriptions of the setup of Putin’s elite, such as “the Kremlin towers,” “the solar system,” “the Politburo” or “the tsar’s court” are no longer applicable in today’s circumstances. They have been replaced by a corporate pyramid and functional layers which are branches of the nomenklatura bureaucracy.

Five branches of the nomenklatura bureaucracy can be defined as follows:

- Power

- Technocratic

- Business (includes state and private business)

- Political-technological

- Regional

Each representative of this bureaucracy is a cog in the machine, who carries out strictly defined functions. Each cog is interchangeable; the limits of the responsibility and the functionality of each official is determined from above. The reshuffle which took place in May 2024—the largest reshuffle during the war—saw movement from power to management (Patrushev); from management to power (Belousov, Savelyev, Fradkov and Tsivilyov); and businessmen to management (Kovalchuk). There was a huge transfer into state management of managers who had served their time in the regions: technocrats (Starovoyt); businessmen (Tsivilyov); political technologists (Degtyaryov); and power (Dyumin).

Among the ratings of the one hundred leading political figures in Russia, almost half—46 of them—occupy management/technocratic roles; around one in six are political technologists (17), business (16) and from the power ministries (15); while one in twenty is from the regions (six).

Those from the power ministries have increased their representation by a quarter compared to the period before the war; the managers and technocrats by ten percent; the business elite has declined by a fifth; and the political technologists by a tenth.

These are frequently the same people, but they have been arranged differently on the chessboard of power. The question of winners and losers as a result of the war in Ukraine does not apply to the Russian elite as a whole, with the exception of big business—notably private business. The businessmen have become more beholden to Putin, and property rights are now relative. All the other groups among the elite are comfortable, preoccupied by their own struggle for survival and prosperity.

Widely-held ideas that there are basic functional corporations and corporate pyramids are far from reality. This is especially the case for the myth about those from the power ministries being the main beneficiaries of the war and about the growth of their influence.

Undoubtedly, the influence of the “power corporations” has grown during the war. Today they determine the goals, the tasks and the whole logic of the country’s development. But this is corporate influence, not personal. On the personal level, the leaders of the power corporations and the secret services have at best held on to their previous positions, although some have been demoted: such as Shoigu who was removed from the post of Minister of Defense and not covered in glory, or Bastrykin (at the Investigative Committee) and Bortnikov (FSB), who have now been granted merely annual extensions, based on their ages.

The war has done away with the image of the all-mighty silovik (representative of the power ministries). Putin deliberately keeps aging bosses of the power corporations in place; but this does not reflect so much his trust in them, as his desire objectively to weaken these powerful corporations on the political stage. According to his logic, these corporations should not appear as powerful organizations.

Accordingly, Rostec under Sergei Chemezov consistently fails to achieve the ambitious programs which the Kremlin has set it in shipbuilding and aviation. Igor Sechin’s Rosneft successfully copes with the budget set for launching remarkable projects, but never manages to achieve the result which has been announced.

On the one hand, there is growth of competition among the corporations for a slice of the budget pie; but on the other, the dismantling of the system of corporations as relatively independent actors.

This dismantling happens in two ways:

- A radical change in the leadership of the corporation, as happened with the Defense Ministry, which was given a wholly civilian leadership, including the minister and most of his deputies;

- The corporation being genuinely weakened politically, deprived of a powerful structure, and with one of Putin’s allies at the helm. This is what happened to the Federal Security Service (the FSB), the Investigative Committee, Rosgvardiya, and the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

Until now, when older strong allies of Putin left, their virtually autonomous corporations disappeared. From being in a separate pyramid, the corporation has simply become a part of the general, centralized one. As Putin’s peers have departed, the very system of corporate quasi-federalism which was built in Russia in the 2000s has not been reproduced; it is becoming a thing of the past. In its place a strict centralized system is being established, which will still work after Putin has gone.

Old and New Models of Management

Today, the disappearing old system created under Putin is operating side by side with the new, technocratic model of management, largely shaped by Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin.

Putin’s model is personal, with outdated elements of the special services system from the KGB/FSB. It works based on influential corporate bosses, with the power resources behind them (fear is a motivator). Mishustin’s model is that of the head of the Presidential Administration, Anton Vaino and his first deputy, Kiriyenko. It is more institutionalized and business-corporate. This works on the division of responsibility and collective decision-making.

With Putin and his allies growing older, the Putin model is experiencing personnel issues. This has led to the appointment to senior posts of Putin’s aides and bodyguards: the Emergency Situations Minister, Alexander Kurenkov; the Director of the Federal Customs Service, Valery Pikalyov; and the Personnel Officer of the Presidential Administration, Dmitry Mironov. Then there are the promotions of other members of the “wider family”: Putin’s relatives (Anna and Sergei Tsivilyov); the children of his friends and allies (Dmitry Patrushev, Boris Kovalchuk, Pavel Fradkov); and even former classmates (Irina Podnosova).

In the Mishustin–Kiriyenko model there are meritocratic mechanisms for the selection and training of personnel. These are programs such as “Leaders of Russia,” “The Governors’ School,” “Time of Heroes” and others.

Putin himself tries to keep up with the times. During the course of the war, the complete personnel bloc in the Kremlin has been changed: three young “commoners,” who are close to Putin and not to some corporation or other, have been brought in to replace a trio of KGB generals. Out went Sergei Ivanov (2011–2016), Anatoly Seryshev (2018–2021) and Andrei Chobotov (2017–2023), and in came Anton Vaino (from 2016), Dmitry Mironov (from 2021) and Maxim Travnikov (from 2023).

In fact, this is less a question of managers than of the way the system functions. In the technocratic model there is a definite division of labor and determination of responsibility. There is a mechanism for consultation and taking collective decisions (such as strategic government sessions to solve major issues), and there are feedback mechanisms (the government’s operational centers and the center for the management of the regions).

Repression as a Means of Boosting Loyalty and Efficiency

In 2014, political repression against the elites acquired a measured, systemic rather than mass character. In addition to being generally intimidatory, it can also perform a purely utilitarian role. For example, it can act as the mechanism for changing the whole leadership of a corporation. This was done in 2024 when Shoigu’s team in the civilian part of the leadership of the Defense Ministry was removed. Repression is often used as a way of distributing property, or as a way of resolving conflicts among the elite.

An important feature of repression is that it affects not only those who violate strict civil or more relaxed intra-elite rules, but it also applies to officials who do exactly the same as the majority of bureaucrats at their level. This may be a case of officials violating numerous conflicting rules governing economic activity, or using their official position to benefit themselves or their loved ones, or the traditional embezzlement of government funds.