The long march of Victory Day – from memory to mobilisation

The Second World War stands as the largest collective trauma in Soviet and Russian history — and virtually the only event in recent memory that unites the entire country. Yet in today’s Russia, Victory Day has lost its original meaning as a day of mourning and has been transformed into a central pillar of state ideology. From Putin’s third presidential term onwards, the holiday has been used as an instrument of domestic mobilisation, a tool for legitimising authority, and a justification for external aggression. It has merged with the rhetoric of Russia’s ‘special path’ and messianic role, becoming part of a quasi-religious national consciousness where the military past simultaneously justifies present-day violence and alleviates anxiety about an uncertain future.

Formation of a new ideology

During the Second World War, the Soviet Union lost over 26 million people – about 15 per cent of its population, and over 20 per cent in its European part. Nearly every Soviet family was affected. In the early post-war years, Victory Day, celebrated annually on 9 May, was seen as a moment of collective mourning and personal grief. It was only under Brezhnev that the day began to be used to strengthen the legitimacy of the wartime generation, especially in the final years of his rule, when the leadership sought ideological justification for blocking generational change.

Even so, in the Soviet period the holiday’s central message was not only the glorification of military heroism and sacrifice but also the desire to prevent another major war – a sentiment similar to Europe’s ‘never again’ principle. Military parades on 9 May were institutionalised only in 1995 under Russia’s first president, Boris Yeltsin, and became a key feature of the country’s modern politics built around symbols.

While the holiday’s deep symbolic importance – particularly for the older generation – had developed long before Putin’s era and persisted regardless of political context, under Putin, especially after 2008, Victory Day became a cornerstone of official state ideology. The event took on an increasingly militarised character, with a heightened focus on showcasing Russia’s military might. At the same time, earlier civilian memory practices – such as the St George ribbon1 and the Immortal Regiment2 – were gradually institutionalised and incorporated into the regime’s canon of symbols.

This trend intensified after the 2011–2012 protest movement, when mass demonstrations in Russia’s major cities challenged parliamentary election fraud and Putin’s return to the presidency. In response to this political instability, the government transformed 9 May into a tool of domestic consolidation. War memory began to serve as a mechanism of social mobilisation, and triumphalist themes, aggressive militarism, and notions of Russia’s historical mission increasingly dominated the holiday’s rhetoric and visual culture – pushing aside themes of loss and resistance to foreign aggression.

By 2014, these narratives merged with Orthodox and Slavophile ideas of Russia’s ‘special path’, recasting the past as a justification for present and future violence. In the same spirit, key events of the Second World War – such as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Katyn massacre, and the importance of Lend-Lease – were reinterpreted to align historical memory with the Kremlin’s agenda.

Instrumentalising the past: how the state uses Victory Day

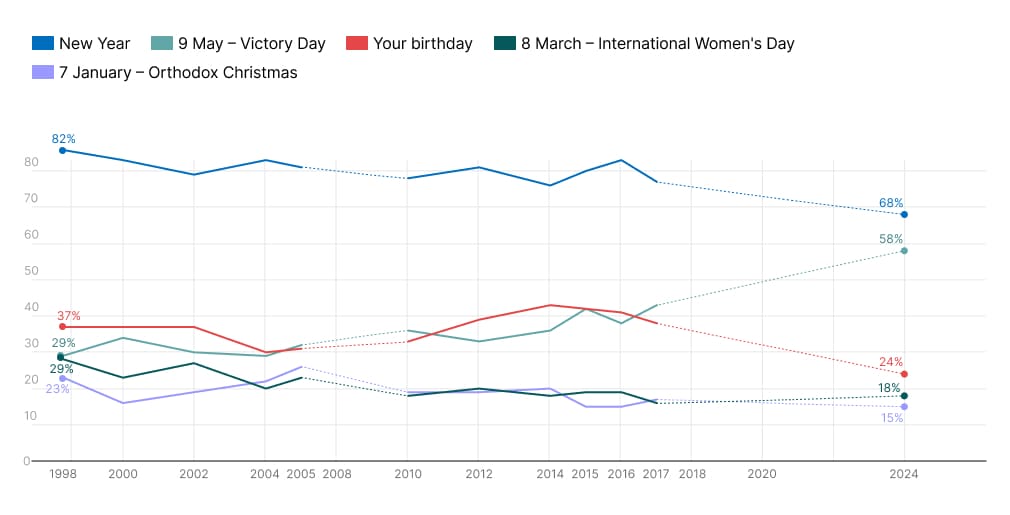

The perception of 9 May as Russia’s main national holiday has strengthened in parallel with its institutionalisation and ideological reframing.

Which of the following holidays are the most important to you?

According to recent Levada-Center data, since 2004 the importance of Victory Day has steadily grown in the public consciousness. A particularly sharp increase occurred after 2014 – in the wake of the annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in Ukraine. By 2024, 58 per cent of Russians named 9 May as the country’s most important holiday, a record figure that confirms its exceptional symbolic status against the backdrop of declining importance of other state and religious holidays.

Although it may seem that the ritualisation of Victory Day is driven by rising patriotic and triumphalist sentiment, this is in fact taking place against a backdrop of growing public anxiety and depression. Studies by the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Psychology show that anxiety is especially pronounced among young people aged 18–24 and 25–34. In these conditions, the image of Victory may play a compensatory role – helping people cope with a loss of direction and control over the future. Much like in the Brezhnev era, the cult of Victory under an ageing authoritarian regime offers the symbolic stability of the past as a substitute for the absence of a meaningful vision for the future.

Ella Paneyakh

Head of Sociology, NEST Centre

At the same time, the turn to the past serves not only to reduce existential uncertainty but also to justify current domestic and foreign policies. This is particularly evident in how historical memory around Victory is used to legitimise modern aggression – above all, the war against Ukraine.

Notably, the 2025 parade is set to feature not only cadets and members of the ‘Youth Army’ but also ‘veterans of the Special Military Operation’ and equipment used during the invasion of Ukraine. The symbolic power of 9 May, deeply rooted in family memory, helps make support for the Russia–Ukraine war psychologically acceptable – even amid economic hardship and heavy battlefield losses. This is precisely the goal of state propaganda, which seeks to portray Ukrainians and the Baltic peoples as descendants of collaborators and inheritors of the Nazi tradition.

In this way, the new war is folded into the context of the old war, turning Victory into a universal political argument of the present.