Xi Jinping in the Russian media: The indispensable partner Moscow cannot fully trust

Russian media hail the China–Russia partnership as a pillar of a new world order. This study shows a more fragile reality: Xi remains peripheral in coverage, closely watched for signs of wavering, exposing a relationship driven by necessity rather than shared strategic vision.

Introduction

When Xi Jinping stood beside Vladimir Putin on Red Square on 8 May 2025 as Russian tanks rolled past, Russian state media presented it as a watershed moment. ‘Xi Jinping named Putin as an ally in forming a new world order’, ran the headlines. Russian media treated it as definitive proof that Beijing had chosen to deepen its ties with Moscow despite western warnings.

However, beneath the celebratory framing lay a more complex reality. This analysis examines Russian-language media coverage of Xi Jinping from January 2025 to January 2026 – the first year of Donald Trump’s second term and the fourth year of the war in Ukraine, which Russia has still failed to win. This period was chosen as the focus of the study because, with Western sanctions tightening and military progress stalling, Moscow’s dependence on Beijing was greater than ever before. Using the same methodology applied in an earlier analysis of Donald Trump’s portrayal in the Russian media, the NEST Centre data science team tracked how Russian propaganda presented this crucial relationship to its audiences.

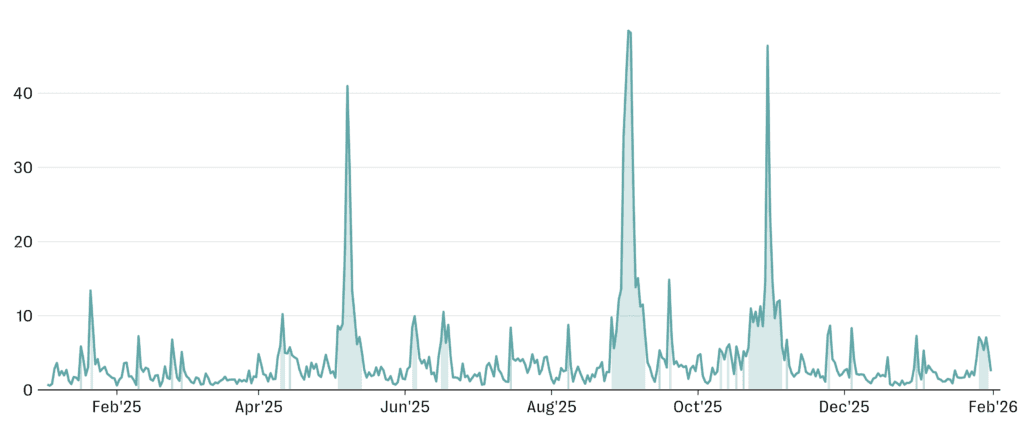

As the figure below shows, Xi’s media presence remained remarkably low throughout the year – roughly 20-50 times below Trump’s typical coverage levels. Xi appeared prominently only when intersecting with Russian or American narratives: summits with Putin, phone calls with Trump, or moments of symbolic solidarity. Otherwise, China’s leader remained largely peripheral to Russian audiences.

This asymmetry reveals something important. Despite the Sino-Russian partnership’s centrality to Moscow’s foreign policy, the Russian media presents China as a useful partner rather than a captivating story. The coverage reveals less about Xi himself than about how the Kremlin frames a relationship it needs but does not control.

Xi Jinping’s media presence index in Russian-language media, January 2025 to January 2026

The partnership of necessity

Russian coverage of Xi during this period consistently portrayed the relationship as strategically vital – but the framing revealed underlying anxieties. When Putin called Xi on Trump’s inauguration day, Russian analysts described it as a counter-signal: evidence that the Moscow–Beijing axis would prove ‘stronger than the new Washington administration’.

By late February, on the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Xi declared Russia a ‘good neighbour impossible to separate, a true friend sharing joys and sorrows’. The Russian media emphasised that the relationship was ‘not subject to third party influence’ – a pointed reference to American attempts to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing. Yet the very need to emphasise this immunity suggested vulnerability. Throughout the year, Russian coverage carefully monitored every Xi–Trump interaction – phone calls, trade negotiations, the Busan summit – for signs that Beijing might limit ties with Moscow to please Washington. The answer was consistently reassuring, but the anxious watching revealed who held the weaker hand.

Victory Day: Symbolism over substance

The May Victory Day visit represented the apex of symbolic unity. Xi wore a St. George’s ribbon.1 Chinese troops marched in the Red Square parade – the ‘largest foreign military presence’ at the event.

But symbolism dominated where substance was thin. Xi personally presented a proposal for peace in Ukraine, calling for a ‘fair, lasting, and legally binding’ agreement – language that implicitly questioned the legitimacy of Russia’s war aims. The Russian media portrayed this as Xi taking ownership of peace diplomacy, yet the proposal gained no traction.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry’s warning that any Ukrainian attack during the parade would be classified as an attempted assassination of Xi – grounds for a Chinese military response – received extensive coverage. The Russian media presented this as evidence that China now had a stake in Russia’s security. A more sober reading suggests that Beijing was protecting its leader while visiting a war zone rather than committing to Russia’s defence.

The triumvirate that wasn’t

During the summer of 2025, Russian coverage experimented with a new framework: the Putin–Xi–Trump ‘triumvirate’, which was supposedly reshaping global power. When The Economist depicted Trump, Putin, and Xi on its cover under the headline ‘Don’s New World Order’, the Russian media treated it as Western recognition of a transformed reality.

Xi’s calls to oppose ‘unilateral intimidation’ and build a ‘fair multipolar world order’ were amplified as evidence of shared thinking. Russian coverage framed this as a sign that China and Russia are aligned against American claims to be the world’s leading power.

However, this framing obscures more than it reveals. Beijing seeks the gradual reshaping of global institutions to expand Chinese economic influence – a patient, commercially-driven project. Moscow demands acknowledgement of its great power status and the right to block decisions in its neighbourhood, but at the same time encourages the rapid dismantling of the post-Cold War order with the aim of reformatting European security arrangements on its own terms. These are fundamentally different strategic logics that happen, for now, to share an adversary.

The limits of coordination

The highest media attention of the year came in early September during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit and China’s commemorations of the 80th anniversary of victory over Japan. The imagery of Putin, Xi, and Kim Jong Un standing together on Tiananmen Square was carefully curated and extensively amplified. One headline captured the intended framing: it was evidence of a ‘new geopolitical alliance against the Western world’.

But Russian coverage also revealed the relationship’s limits. Xi announced that SCO economies were approaching a combined GDP of $30 trillion, positioning the organisation as a counterweight to Western institutions. Russia contributed little to this economic weight. When Xi met India’s Modi for the first time in seven years, declaring that ‘Dragon and Elephant must unite’, the Russian media noted American alarm. Yet it failed to note that Russia was irrelevant to this Asian great power reconciliation.

The patriotic Russian writer Alexander Prokhanov described the parade in Beijing as humanity ‘casting off war-torn vestiges to enter a new era of multipolarity’. Yet China’s definition of multipolarity means a world of several great powers. In Moscow’s framing, it means a narrower configuration where Russia is at the top table together with China and the US. The gap between these visions was not examined.

The asymmetry exposed

By autumn, two storylines dominated coverage: Xi’s dramatic purge of China’s military leadership, and his late October summit with Trump in Busan.

The Russian media framed Xi’s dismissal of nearly a fifth of the generals he had appointed as an intensification of his anti-corruption campaign, drawing comparisons to Russia’s own Defence Ministry housecleaning. But the purges’ scale was unprecedented. By the end of the year, only two of seven Central Military Commission members remained in place. Comparisons with Stalin’s 1937 purge of the Red Army’s military leadership appeared in Russian commentary: historically informed audiences would recognise this as cautionary, not congratulatory.

The Trump–Xi Busan summit exposed Russia’s subordinate position most clearly. The hundred-minute meeting produced partial trade de-escalation: tariffs were reduced, Chinese export controls suspended, and American soy shipments restarted. Trump rated it ‘12 out of 10’ and called Xi a ‘great leader’.

Russian coverage focused on what Trump did not raise: Chinese purchases of Russian oil. Bloomberg analysts, cited in the Russian media, called this a failure to put pressure on Beijing and said that it would leave Western sanctions against Russia toothless. One Russian expert commented that China would not limit ties with Russia ‘to please the USA’. The relief was palpable. But so was the reality: Russia’s economic lifeline depended on whether an American president chose to pressure China – a decision Moscow could not influence.

Into the New Year: Instability acknowledged

January 2026 brought two developments that the Russian media could not easily frame as a validation of the China–Russia partnership.

On 3 January, US military strikes on Venezuela led to the capture of President Maduro – just hours after he had met with Xi Jinping’s special envoy Qiu Xiaoqi to discuss strategic cooperation. Russian coverage noted the timing with evident discomfort. Trump’s dismissive claim that the operation would cause ‘no problems with China’ was reported sceptically. The episode also illustrated China’s expanding Latin American presence – and its potential vulnerability to American military action in regions where Beijing has no defensive reach.

Later that month, an extraordinary development commanded attention: Zhang Youxia, Xi’s deputy on the Central Military Commission and his closest military ally, came under investigation. The Western media reported allegations that Zhang had passed data about China’s nuclear weapons programme to the United States. Russian coverage noted that nearly half the generals appointed by Xi were now under investigation, with reports of military columns moving towards Beijing and other troop movements being banned. Some Russian commentary again invoked the Tukhachevsky affair of 1937 – Stalin’s purge of the Red Army leadership – suggesting both a historical parallel and a cautionary tale. By the end of the period under analysis, only two of seven Central Military Commission members remained in place: Xi himself and the head of the anti-corruption commission conducting the purges.

The dependent partner

For Western policymakers, the year’s coverage offers a clear conclusion: this is not an alliance forged by a shared vision, but a dependence born of shared adversity. Moscow watches Beijing anxiously for signs of wavering – every Xi–Trump interaction tracked, every hint of rapprochement with Washington scrutinised. The Russian media presents each summit as validation, each ceremony as proof of alignment – yet the very intensity of this framing reveals anxiety. A confident partner does not need constant reassurance.

Key practical implications follow from this asymmetry. Efforts to drive Moscow and Beijing apart will be portrayed as proof of the partnership’s importance – and may, paradoxically, push Moscow into a deeper dependence that neither side truly wants. Under the current paradigm of China–Russia relations, China gains a discounted resource supplier and a source of diplomatic support; Russia gains an economic lifeline it cannot secure elsewhere. Neither seeks more than this from the other, yet external pressure could lock both into arrangements that serve neither’s long-term interests. What the coverage reveals – beneath the often triumphal framing – is a partnership sustained by circumstances rather than conviction, and constrained by the very imbalance that holds it together.