Russia’s negotiating position is undergoing a gradual transformation – shifting from rigid and largely unrealistic demands to more pragmatic considerations focused on consolidating what has already been achieved. However, the attempt to present a compromise as a form of victory carries the risk of internal conflict: the militarist wing, once mobilised in support of the war, may perceive a freeze in hostilities as a betrayal – and turn from an ally of the Kremlin to a threat.

A signal to Trump: why the Kremlin is returning to negotiations

Vladimir Putin’s proposal to resume peace talks reflects not so much a genuine willingness to compromise as a need to resolve a strategic dilemma: whether to continue the war in pursuit of military gains, or to consolidate what has been captured and seek at least partial recognition of these claims from the West – above all, from the United States. On the one hand, the Russian army finds itself in a war of attrition with costs mounting and generals’ promises unfulfilled. The Kremlin recognises that the goal of a decisive defeat of Ukraine has not been reached, and the scenario of a prolonged war is becoming increasingly unattractive. On the other hand, the Kremlin still has the resources to sustain the conflict for at least another year – and this option has not been ruled out.

The return to negotiations is, above all, a signal to Donald Trump. Moscow assumes that Ukraine is not a subject in its own right and that Europe is an ideological adversary incapable of pragmatic dialogue. The Kremlin sees the United States – and specifically the Trump administration, eager for a swift and visually impressive settlement – as the only viable channel through which it can ‘lock in’ its gains.

Hence the flirtation with the idea of negotiations: the Kremlin signals readiness for dialogue but insists on setting the terms. The composition of the Russian delegation suggests that Putin prefers to proceed at his own pace. At any moment, he could revert to deliberately unacceptable demands and derail the process if his conditions are not met. This scenario was already tested in 2022 when Putin blamed the breakdown of the Istanbul process on Kyiv and its Western partners.

How Russia’s negotiating position is shifting

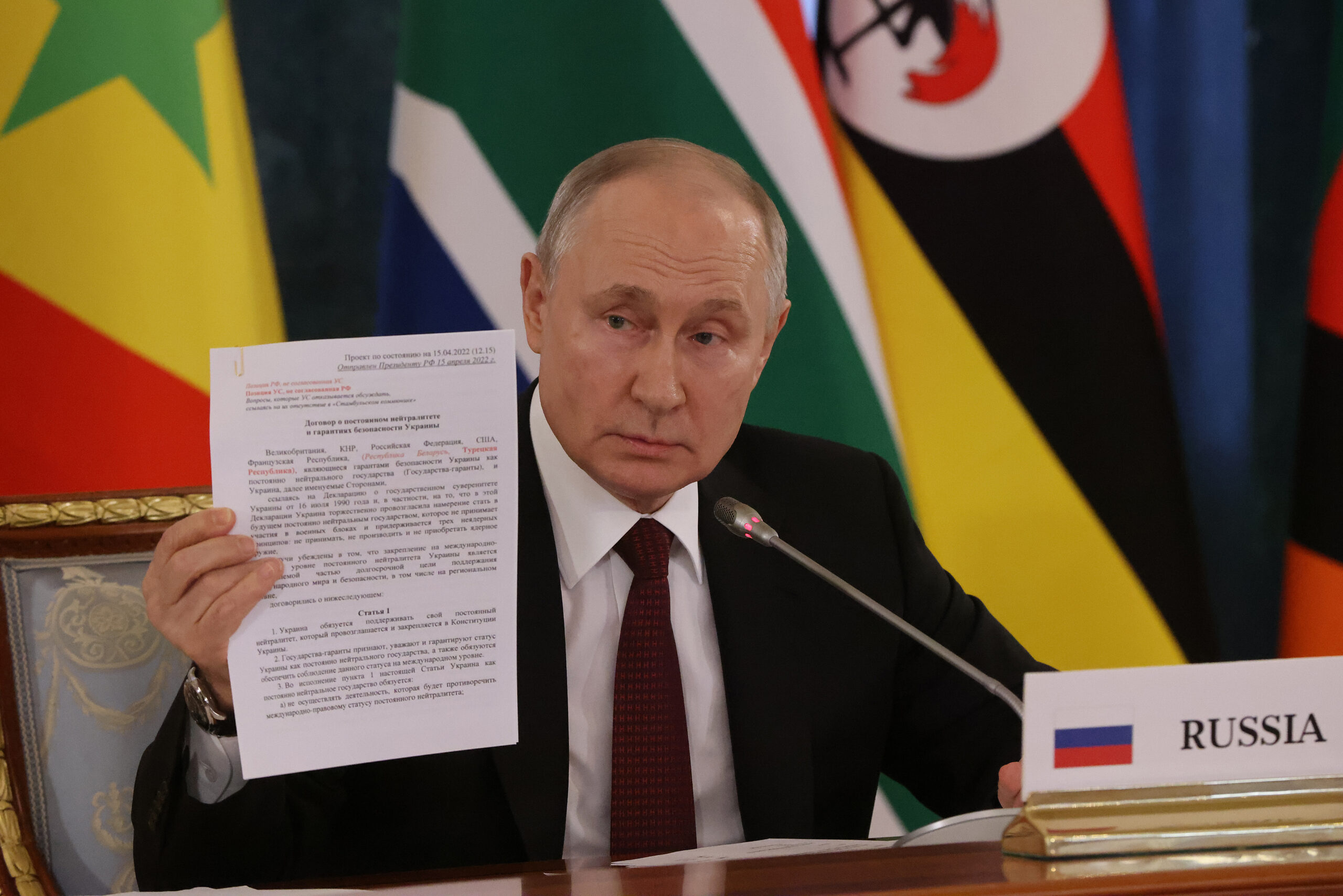

Despite these tactical manoeuvres, the substance of Russia’s position is changing. In 2022, Moscow’s proposals mixed a few limited, potentially acceptable points (such as Ukraine’s permanent neutrality with no obstacle to its EU membership aspirations) with clearly unviable demands, including the radical downsizing of Ukraine’s armed forces, official status of the Russian language, and other conditions directly affecting Ukraine’s internal affairs.

Now the framework has become narrower and more pragmatic. The Kremlin is gradually moving away from maximalist rhetoric and focusing on outcomes that can be presented domestically as a ‘victory’:

- Securing territorial gains, even if not within the full administrative boundaries of all the annexed regions, but at least along the current front line or the Dnipro River. In Putin’s geopolitical logic, the Dnipro represents a natural dividing line that could anchor Russia’s military achievements. It would be difficult for either side to alter this line unilaterally, creating the perception of a controlled end to a phase of the conflict. While bargaining may still occur over sections of the front that have not yet reached the Dnipro, the overall balance appears stable.

- A guaranteed commitment that Ukraine will not join NATO. This has already happened de-facto: the United States no longer actively supports Ukraine’s NATO aspirations, and the Kremlin may consider this a goal achieved.

As for demands such as ‘denazification’ and ‘demilitarisation’, Putin, ever the pragmatist, understands their infeasibility. These rhetorical formulas are retained more as levers of pressure and bargaining chips than as genuine conditions.

From the ‘party of war’ to the ‘party of peace’

Compared to 2022, the stakes for the Kremlin have risen considerably. Putin has invested human lives, political capital, military resources, state finances, and propaganda efforts – now he needs to show results. Even though the regime’s dependence on public opinion is limited, it still draws support from various social groups, all of whom now expect an answer to the question: what was all this for?

In February 2025, when talks of peace had already begun, the share of respondents who would not support a decision by Putin to end the war rose from 31 per cent (in 2024) to 46 per cent.

The most vulnerable group is the hardline militarist camp – the most radical segment of war supporters. For them, any compromise, truce, or ‘concessions’ will appear as a betrayal of the war’s original goals. A return to pre-war conditions would be seen as abandoning what they regard as the war’s positive societal changes interpreted as the restoration of social justice, a revival of patriotic values, and the suppression of individualistic and ‘perverse’ pro-Western tendencies.

Their mindset is closer to military revanchism than to the loyalist consensus. Even those who recognise that the war’s objectives are no longer attainable through military means still argue that the fighting must continue. In this logic, war becomes an end in itself – a symbol of resolve, mobilisation, and political identity. Any cessation of hostilities, even a temporary one, will be viewed as capitulation.

Against this backdrop, the Kremlin might attempt to build a broader base of support by appealing to those who had tried to ignore the war altogether. As the consequences deepen, they are increasingly hoping for normalisation and a return to pre-war conditions. However, such a turn inevitably conflicts with the openly militarist segment of society – a smaller but far more politically active force.

Ella Paneyakh

Head of Sociology, NEST Centre

As this configuration evolves, the ‘party of war’ risks becoming a threat rather than an ally – especially if a freeze in the conflict is accompanied by attempts at domestic stabilisation and renewed international engagement. This ‘party’ may even become the next target of repressions. Just as Stalin purged a number of war heroes after 1945, Putin may eventually turn the repressive apparatus on the most active proponents of militarism.