Russia’s decision to bring North Korean troops into its war in Ukraine marks an unprecedented escalation and a calculated geopolitical message. While the deployment strains ties with China, it signals to Western allies that Moscow can stir instability far beyond Europe. For Seoul, the real concern is what Pyongyang might be receiving in return.

Summary

- The Kremlin’s unexpected decision to bring North Korean soldiers to fight Ukraine is more than just a military move. It sends a clear political message to Ukraine’s western allies that it can affect their interests in other parts of the world.

- South Korea has good reason to ask what payment its northern neighbour is receiving from Russia and how any deliveries of military technology might impact its security.

- Since the end of the Korean War of 1950–53, North Korean soldiers have operated abroad in other conflicts, but in each case, this has involved relatively small groups of soldiers. The deployment to Ukraine of a 10,000-strong contingent is unprecedented.

- China is unhappy about North Korean soldiers being sent to Ukraine, but not to the point where it is ready to put pressure on Moscow and Pyongyang.

- Beijing is concerned that an excessive rapprochement between the two could weaken its influence on North Korea. It also does not want to see excessive strengthening of North Korean military capabilities.

- The deployment of North Korean troops is part of a broader game that the Kremlin is playing to re-shape the international order in line with its interests.

Russia’s motives

The idea that North Korean soldiers could fight on Russia’s side in the war in Ukraine appeared unexpectedly. Just three weeks after rumours began to circulate about their participation, President Putin confirmed it at the BRICS summit on 24 October.

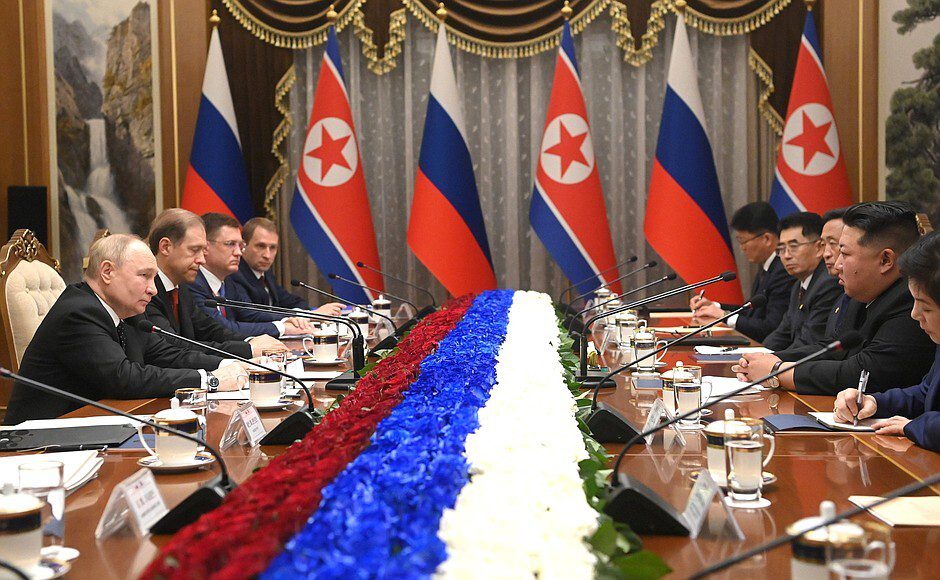

It is impossible that an agreement to send North Korean troops to Russia could have been reached quickly. This was an unprecedented political decision for each side. The idea must have been conceived earlier in the year during meetings between President Putin and the North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un to discuss the war. Since September 2023, Pyongyang has been supplying artillery shells and missiles to the Russian army for use in Ukraine.

It is notable that when the North Korean forces arrived in Russia, the State Duma had still not ratified the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement (CSPA) which had been initialled on 19 June 2024 in Pyongyang by Putin and Kim. Putin signed the Agreement into law only at the start of November, after his October confirmation that North Korean troops had joined Russia’s war effort.

Such long-term thinking illustrates an unexpectedly high quality of planning in Russian foreign policy. When drawing up the agreement signed in June, Moscow and Pyongyang held something in reserve with a view to deepening cooperation. Sending North Korean troops to Russia in October, before the CSPA was ratified, suggests that this reserve was called into play earlier than planned.

It is unlikely that the use of North Korean troops was a strictly military measure caused by a lack of manpower in the Russian army. Although sustaining soldier numbers is a serious challenge for the Kremlin without further mobilisation, it is not an insoluble problem. The Russian army has so far been able to cope with casualty rates believed to be over 1,000 per day in recent months. In any case, if reports are correct, North Korea can currently only offer a maximum of 100,000 troops in support of Russia.

Although the Russian leadership is worried about the possible political consequences of announcing a second wave of mobilisation, these concerns should not be exaggerated.

Judging by the fast growth in the sums of money being offered to attract ‘volunteers’ to the frontline, the Kremlin is working hard to avoid additional mobilisation. The lowest amount now being offered to new recruits is 800,000 roubles (about $8,000), with the average coming close to 1.7 million roubles ($17,000). The recent adoption of a law authorising debt forgiveness of up to 10 million roubles of arrears (around $95,835) in return for one year of military service in Ukraine is the latest blandishment on offer to potential recruits.

A further challenge for the Russian army is that the reserve drawn from the prison system to swell combat forces is exhausted.

If the goal of the CSPA was simply closer military cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang, it is unlikely that North Korean soldiers would have joined the war against Ukraine.

It is more probable that bringing North Korean soldiers into the war in Ukraine was a military-political move, part of Russia’s asymmetric strategic response to the West sending ever more high-tech military aid to Ukraine. It was a political signal to the West showing that the ‘Russian cannon’ is fully unleashed, and will strike where it wants and stop at nothing.

The Russian armed forces have been using foreigners on the frontline since the early days of the war. Coming mainly from Central Asia, they have signed up on an individual basis. In the case of North Korea, it has been sending workers to Russia since Soviet times. They have mainly been employed in logging, construction and fish processing. South Korean media reported in June that North Korean construction and engineering troops were heading to occupied Donbas to support reconstruction efforts. There was speculation that they would also assist in building fortifications. So the participation of North Koreans in military action was a logical continuation of their involvement.

In addition, using North Korean soldiers in the war against Ukraine can be viewed as part of Russia’s nuclear blackmail of the West. Russia has been playing this game on and off since 2007, but particularly seriously since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It is as if the Kremlin is saying, ‘If we’ve decided that we can bring a foreign expeditionary force into Russia and throw them on to the frontline, then you should have no doubts that we could also decide to use nuclear weapons’.

Finally, the appearance of North Korean troops in the Ukrainian theatre of war could be interpreted as Russia’s geopolitical blackmail of the West on all fronts: ‘Wherever we can, we’ll harm you; wherever we can, we’ll help your enemies; wherever we can, we’ll unite and outflank you.’

Consistent with this approach is the unambiguous hint that Russia is sending missile technology to Pyongyang. North Korea’s launch on 31 October of a ballistic missile which reached a greater height and travelled a greater distance than any launched previously, followed on 5 November by the launch of a further five shorter-range ballistic missiles, looks like Russian payment for the ‘brotherly’ help North Korea is giving in manpower.

Another stimulus for Russia’s military alliance with North Korea was the growing clamour in several western countries for Ukraine to be allowed to use long-range Western weapons to strike targets in Russia. This allowed Moscow to claim that it was activating its military partnership with North Korea because of the participation of Ukraine’s western allies in military operations against Russia. Undoubtedly, discussions between Moscow and Pyongyang took on a more practical turn after the Ukrainian army began its military operation in Russia’s Kursk Region in early August.

Russia was not ready to repel this attack, nor was it prepared to move troops from Donbas to deal with it. At the time, Russia was starting to make larger territorial gains in Donbas and the Russian high command did not want to dance to Ukraine’s tune. Retired Lieutenant-General Andrey Gurulyov, now a member of parliament, even raised the question of using conscript soldiers in the Kursk Region. At this point, the question of using North Korean soldiers suddenly became particularly relevant.

Russia had long been determined to show the West how ‘decisive’ it could be. With the Ukrainian incursion providing embarrassing evidence of Russia’s lack of defences and vulnerability to surprise, it created an urgent military need for a compact, armed and well-coordinated expeditionary force numbering several tens of thousands of men. Such a force would have no real effect on the overall outcome of the war, but could prove decisive in driving Ukrainian forces out of Russian territory. The success of this operation would create abundant positive propaganda.

So in the autumn of 2024, Moscow formulated a clear request for the participation of North Korean forces in a limited military operation on Russian territory. The Kremlin took the trouble to formally demonstrate the legitimacy of the presence of these troops in line with its agreement with North Korea.

At the start of the operation at least, the idea was that North Korean soldiers would be used only on internationally-recognised Russian territory. How this request for assistance would be carried out in practice would depend on several factors: the capabilities of the North Korean soldiers, the political priorities of their leadership, and, lastly, on the position of China. Beijing, in turn, was watching carefully to see how Washington would react.

Clearly, using North Korean units in the Kursk region is a test case. Seen from Moscow, their deployment coincides with upheaval in the West demonstrated by the re-election of Donald Trump and the collapse of the ruling coalition in Germany. If the West does not react decisively and with one voice, this presents an opportunity to deploy more foreign troops in the war against Ukraine – and not just on Russian territory.

The visit by Russian defence minister Andrey Belousov to Pyongyang in late November was a further signal to the US and its allies in East Asia that Russia views the expansion of its military ties with North Korea as a priority task.

The legal basis for sending troops

Russia and North Korea defined in advance the legal framework for sending North Korean units to the frontline in Ukraine. As noted above, the CSPA provided the necessary framework. The Agreement was ratified by the State Duma, approved by the Federation Council and signed by Putin in line with established procedure. In terms of international law, such agreements are not exceptional.

The original basic inter-governmental agreement between the USSR and North Korea was signed in 1961 and included provision for a military alliance. This agreement was partially amended in 1996, and the point about a military alliance became invalid. The Treaty on Friendship, Good Neighbourliness and Co-operation signed by Russia and North Korea in 2000 refers only to ‘co-operation in defence and security in line with mutual interests’ (Article 6).

But the CSPA, in Articles 3 and 4, establishes a military alliance between the Russian Federation and North Korea.

Article 3 states:

Should a direct threat of armed aggression be created against one of the Sides which is party to this act, one of the Sides may call for the immediate operation of the bilateral channel for the holding of negotiations to coordinate their positions and agree on feasible practical measures to assist each other so as to deal with the threat which has arisen.

Article 4 states:

Should one of the Sides be subjected to armed attack by any state or group of states and is as a result at war, the other Side will immediately come to the first Side’s assistance with military or any other means at its disposal in accordance with Article 51 of the UN Charter and the laws of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation.

The decision by the leaderships of Russia and North Korea to create a military alliance raised eyebrows among many observers. Most considered it excessive and not in keeping with the level of Russia-North Korea relations at the time. With hindsight, it would seem logical that this radical step was taken specifically to create a legal basis for the participation of North Korean troops in the war with Ukraine. Such actions are typical of Putin who is inclined where possible to have a legal foundation for his actions.

It is worth pointing out, though, that the sending of troops was not fully ‘legal’. When North Korean soldiers arrived on the territory of the Russian Federation, the ratification of the CSPA was not complete. Putin had only just introduced it to the State Duma. From the point of view of international law, without the completion of these formalities, the agreement was only initialled and therefore no more than a statement of intent. This suggests that the need to use North Korea’s ‘military services’ arose suddenly, and that the operational plan had not foreseen such an urgent need for activation of the Agreement.

The participation of North Korean troops in foreign conflicts

North Korea has no experience of sending significant military contingents abroad to take part directly in military actions.

Since the end of the Korean War of 1950–53, North Korean soldiers have actively operated abroad and taken part in a few international conflicts, but in each case this has involved relatively small groups of soldiers.

The Vietnam War: In 1967–68, around 100 North Korean pilots were stationed in Vietnam, along with a number of technical aviation personnel. They flew Soviet-made MiG-17 and MiG-21 fighters bearing North Vietnamese insignia, and took part in aerial combat with US and South Vietnamese forces. The fact that these North Korean pilots were in Vietnam was considered a state secret. The first details of their involvement only emerged just over 20 years ago.

North Korea also sent at least two groups of observers into South Vietnam where they studied the tactics and modus operandi of the South Vietnamese partisans.

There were also groups of North Korean specialists engaged in psychological operations in Vietnam. A significant number of South Korean soldiers took part in the war, and the North Korean specialists targeted them with specially devised propaganda.

The Middle East: Small groups of North Korean pilots were sent to Egypt and Syria to take part in military actions against Israel at the time of the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 (in Syria) and 1973 (in Syria and Egypt). After Egypt cut its ties with the USSR in 1973, the then Egyptian President, Anwar Sadat, who at one time commanded the Egyptian air force, invited North Korean military personnel to fill the gap left by Soviet advisers and pilots. They were able to operate the Soviet air defence systems that Moscow had deployed, as well as MiG-21 aircraft. According to Chinese media, as many as 1,500 North Korean specialists may have been deployed to Egypt.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a few North Korean military personnel were sent abroad as military advisers. They usually provided technical assistance on the use and maintenance of military technology which North Korea was then actively exporting to developing countries. At the time, the North Korean military-industrial complex specialised in the production of cheap and simple copies of Soviet and Chinese weapons for delivery to other developing countries.

In a few instances, North Korean specialists were engaged in the training of guards for leaders of countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. These were just small groups of servicemen, mainly officers. In 1984, the CIA prepared a secret report on the activities of North Korean servicemen abroad, which claimed that there were 450 North Korean soldiers based in 20 countries. The overwhelming majority of these (in groups of between 50 and 100) were in Iran, Madagascar, Mozambique, the Seychelles and Uganda. It appears that the largest contingent of North Korean military personnel was stationed abroad in the early 1980s.

For a country as small as North Korea to have deployed military advisers and personnel so widely is very unusual, even if the numbers involved have been insignificant. The deployment of a 10,000-strong contingent to Ukraine is an unprecedented commitment for the KPA.

Labour export and wages

However, for North Korea, sending troops to Russia has a precedent in a different area. It can be considered a form of labour export.

Pyongyang has sent labour abroad over decades. Virtually since its establishment, the country has dispatched its citizens to other countries, mainly as semi-skilled or unskilled workers in areas such as logging, construction, food and other light industries. In the case of North Korea, UN Security Council Resolution No. 2397 (2017) forbids this kind of external economic activity, but certain countries – Russia and China above all – ignore it and have not suffered any consequences as a result.

Resolution No. 2397 came into full force in December 2019. This led to a reduction in the number of North Korean workers abroad, but did not put a stop to the practice. According to UN specialists, there were 100,000 North Korean labourers working outside the country in 2023, contributing about $500 million annually to the North Korean budget.

The specifics for how the workers’ wages are paid depend on the host country and also the type of employment. The workers themselves receive between 25% and 65% of the allotted wages, with the balance sent to the North Korean government.

It can be expected that this tried and trusted system will be applied also to the North Korean soldiers. They will receive a pre-set amount of their nominal salary (likely to be 10–30%), probably as a monetary allowance, and the rest of the money will go to the national budget.

However, the comparison with the labourers who work abroad is only partial. There is no precedent for the North Korean army taking part in a foreign war, meaning that these soldiers are not yet ‘qualified’ to start ‘work’ immediately in the same way as those in the civilian sector.

As some media have reported, it is possible that the North Korean soldiers may – to some extent, at least – be used not for fighting, but on construction and engineering projects behind the frontline. The Korean People’s Army has vast experience of constructing fortifications – principally tunnels, as well as bunkers and underground shelters.

The provision of shells and weaponry

Ever since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it has been clear that large calibre artillery has been one of the most important forms of weaponry used in this war, in conjunction with drones. North Korean military doctrine has always emphasised the importance of the massive use of artillery to fight an enemy. As a result, the country has built up huge reserves of large calibre artillery shells, most of which match Russian standards. This means that North Korea is one of the few countries in the world capable of providing the shells needed by the Russian army.

North Korea began sending artillery shells to Russia no later than autumn 2023, although officially the leadership has not so far acknowledged its role as a supplier. This should be borne in mind when assessing the significance of official statements coming from North Korea. It is not known exactly how many shells North Korea has sent to Russia, but all sources agree that the figure is in the millions. This assessment is based on an analysis of satellite images, which make it possible to count the number of containers in transit from North Korea to Russia.

In August 2024, South Korean military intelligence said that 13,000 containers had been sent into Russia from North Korea since the end of 2022. Assuming that these containers were used solely for the transportation of 152mm artillery shells, they could have contained around six million shells.

However, that is a maximum estimate. There are indications that North Korea has sent Russia other weapons systems, including some types of ballistic missiles, so these containers cannot have contained just shells.

It should be noted that sending weapons and troops abroad are clear violations of UN Security Council resolutions concerning North Korea.

The size of the North Korean contingent

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) had 1.28 million personnel in 2023. However, the combat readiness of a large number of KPA units leaves much to be desired. Military personnel are used mainly as labourers on construction projects or in agriculture, which clearly limits their training for combat.

Nevertheless, the KPA has around half a million soldiers who could theoretically be sent to Ukraine. It is most likely that Pyongyang would send special forces personnel who number around 60,000 in total, and the so-called ‘light infantry’, which is a less strict version of the special forces with 120,000 soldiers.

Both the ‘light infantry’ and the special forces are considered elite formations which have undergone intensive military preparation and are trained to fight at the rear of the enemy, and in small groups isolated from the main concentration of forces.

Military specialists believe that North Korea could make some ten per cent of these two divisions available to Russia without affecting its own military preparedness. That would be between 15,000–20,000 soldiers from special forces and the light infantry.

The KPA also has combat-ready infantry, based mainly along the demilitarised zone (in reality the border between North and South Korea), and around Pyongyang. If Russia needs reinforcements for the war against Ukraine, North Korea could increase the size of its contingent to 60,000. It is likely that North Korea will operate a rotation system to give the maximum number of soldiers combat experience. In the view of some experts, this could mean 100,000 soldiers being sent to the war.

The North Korean soldiers undoubtedly have certain advantages. They have high levels of physical endurance and can put up with hardship since they are not used to comfortable living conditions. Nevertheless, in battlefield conditions, the specifics of the North Koreans’ military training could cause problems.

The KPA was modelled on the Soviet Army and led by Soviet military advisers. It has maintained the traditions of the Soviet military system, but with the addition of the Chinese concept of ‘a people’s war’. The majority of its senior officers and generals who trained abroad are graduates of Soviet military colleges. As a result, the foundation of their military thinking is a slightly modernised version of the Second World War. This could create problems on the Ukrainian battlefield, where new technologies and tactics are being used.

Communication could also prove to be a serious obstacle. The majority of North Korean soldiers either do not speak Russian or have a very limited command of the language.

Advantages for North Korea

Why might the North Korean leadership be interested in sending its troops into the Ukrainian theatre of military operations?

The economic aspect: The average pay for a Russian private soldier in the combat zone is around $2,000 a month. It is likely that Russia will pay the North Korean troops a similar or slightly smaller sum of which, as outlined above, between 70–90% will go directly to the national budget.

North Korea is receiving significant additional income: 15–20,000 soldiers serving in the war could bring their country around $100 million in a few months. Should more troops be sent into the battle zone, this sum will grow proportionately. Even in the best of times the whole foreign trade turnover for North Korea has never exceeded $7 billion dollars, so $100 million would be a noticeable contribution to the North Korean state budget.

Figure 1. Payments to Military Personnel for Signing a Contract in 2024

Ethical concerns are unlikely to bother the North Korean leadership. Recent decades have shown that the North Korean political elite regards the population of the country as a renewable resource (the birth-rate in North Korea is 1.8 children per woman). People can be sacrificed for ‘the good of the country’ or, more accurately, for the good of the regime. Nor will there be any internal political problems. North Korean soldiers dying in Ukraine will not cause unrest among the people. In principle, there are no social conditions in North Korea which might lead to this.

Access to nuclear technology: The troops being sent to Ukraine will be a bargaining chip in North Korea’s diplomatic exchange with Russia. North Korea wants to receive as much Russian military technology as it can, including nuclear and missile technology.

So far, it appears that the Russian side is cautious about sending North Korea military technology since Moscow considers its proliferation to be both dangerous and undesirable. However, should the need for North Korean troops increase, their leaders may be able to obtain concessions from Russia regarding the transfer of sensitive equipment.

The Russian leadership also has something to gain from this. They are using the threat of transferring sensitive military technology to North Korea to put pressure on South Korea. Russia is letting South Korea’s leaders understand that it could make this technology available to Pyongyang if South Korea were to send direct military assistance to Ukraine, something which it has not so far done.

Combat experience: By sending a sizable number of soldiers to the war, KPA commanders can test their units in genuine combat conditions. There is virtually no one in the North Korean armed forces who has real experience of combat, let alone up-to-date warfare. For any army in the world, this is particularly valuable.

What’s in it for Russia?

Firstly, while Russian soldiers are paid for signing a contract to join the army, North Korean soldiers are not. Given that the payment to enlist is at least $8,000 per soldier out of the federal budget, and on average $15,000 per soldier (which includes a top-up from the regional budget), this represents a financial saving for Russia.

Secondly, it is unlikely that foreigners would be paid extra for time spent on the frontline (which doubles the pay for Russian soldiers), or any bonus for capturing or taking out any Western equipment – for which millions of roubles are paid to Russian soldiers (equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars).

Problems for North Korea

There could be negative consequences for the North Korean leadership from sending soldiers to fight in Ukraine.

The main problem could be that soldiers and officers of the KPA who serve in Russia and Ukraine may come to understand how poorly North Koreans live compared to other countries. Ever since 1960, the North Korean leadership has consistently carried out a policy of self-isolation from the outside world, far stricter than any other country in the socialist camp, including even the USSR in Stalin’s time.

Even in the frontline areas, the standard of living in Russia and Ukraine is much higher than in North Korea. The appearance of villages and towns, even the ones which have suffered serious damage, will indicate to officers and soldiers alike just how far their country is behind the outside world.

Such culture shock could make it difficult to uphold discipline on the battlefield; it will not be the same as exerting control over North Korean civilian workers.

The first fruits of ‘freedom’

According to western media, North Korean soldiers sent by Kim Jong Un to Russia have been enthusiastic viewers of online pornography. In Russia, these soldiers have had access to the open Internet for the first time, and started actively exploring previously inaccessible content.

In North Korea, the Internet is available only to the higher leadership; ordinary citizens are allowed access solely to the state intranet, Kwangmyong, which publishes only government-approved information. Access to pornography is strictly forbidden in the country. The watching or spreading of pornography is punished by 15 years in prison or even the death penalty.

Kim has reason to fear that a potential rebellion against his rule might begin in the officer corps. At the start of the 1990s, a plot was hatched in the North Korean armed forces, involving officers and officials working in other areas of the security apparatus, all of whom had studied in the USSR or other socialist countries. If there was indeed a plot to assassinate Kim Il-Sung, grandfather of the present incumbent, Kim Jong Un, it failed. The alleged plot was discovered, and the ‘plotters’ executed. It came to be known as ‘the Frunze Academy affair’, as some of those responsible had graduated from the Frunze Academy in Moscow. It is possible that senior military officers serving abroad for the first time might come to view their country and its leadership differently.

Desertion could be a different problem. If the Ukrainian army were able to deploy special propaganda, North Korean soldiers and officers might decide to leave their country once and for all.

If Ukraine’s military commanders were able to reach an agreement with the US and South Korea and offer North Korean soldiers the chance to go and live in South Korea – that rich, neighbouring country where people speak their language – this could possibly increase levels of desertion. However, the South Korean leadership takes a very cautious position on the issue of Ukraine, and there are reasons to doubt whether Seoul would actively engage in a mission of this kind.

China’s position

China is unhappy about North Korean soldiers being sent to Ukraine, but not to the point where it is ready to put pressure on Moscow and Pyongyang.

For several months, the Chinese government has been signalling to the international community that it does not approve of the strengthening military cooperation between North Korea and Russia. This includes the sending of both ammunition and soldiers.

Its negative attitude appears genuine for two reasons:

- China is concerned that an excessive rapprochement between North Korea and Russia could weaken its influence on Pyongyang. Until recently, China had a virtual monopoly on humanitarian assistance to North Korea. Without it, the regime would struggle to survive. At present, North Korea can count on Russian support, giving it greater room for manoeuvre and potentially allowing it to ignore China’s demands.

- China fears that North Korea will use the current situation to gain access to Russian military technology that would otherwise be off limits. Excessive strengthening of North Korea’s military capabilities is not in China’s interests. This explains why China has successfully blocked new nuclear tests in North Korea. China’s policy is to keep the country stable but weak economically and militarily. The prospect that a relatively small number of North Korean troops will gain combat experience against the Ukrainian army will not, however, be enough to change the balance of forces on the Korean peninsula and risk a military confrontation.

But it would be wrong to overestimate the scale of China’s dissatisfaction. If it were seriously concerned about Russia-North Korea military cooperation, it could take active steps to stop it. For example, even a small reduction of oil purchases from Russia or the temporary suspension of export of essential goods to North Korea would send an unambiguous signal that Beijing regarded the actions of both as unacceptable. Instead, China has limited itself to a symbolic expression of disapproval aimed first and foremost at the international community. The purpose is to create the impression abroad that China is not responsible for what is happening and cannot influence the situation.

This shows that for China, the strengthening military cooperation between Russia and North Korea may be undesirable, but is nevertheless permissible.

Relations with South Korea and the situation in East Asia

In the short term, sending North Korean soldiers to the war has reduced tensions on the Korean peninsula, since North Korea has temporarily removed a significant portion of its combat-ready troops. This lowers the immediate risk of conflict for South Korea. In the longer term, however, the situation might become even more complicated.

On the one hand, South Korea could reach an agreement with the Ukrainian government to send specialists in psyops to Ukraine, along with intelligence operatives. Interrogations of North Korean prisoners-of-war and defectors would be an important source of information both about the situation in the North Korean armed forces and in North Korea as a whole.

On the other hand, the presence of South Korean soldiers and government representatives in the war zone, and their interaction with Ukrainian government organisations and the Ukrainian army could lead to a significant worsening in relations between South Korea and Russia.

The South Korean government is trying to avoid such a situation, principally in three areas:

Trade: Although trade with Russia has decreased by 30% since the start of the war, Russia remains an important trade and economic partner. The trade turnover between the two countries in 2023 was $15.1 billion.

The threat of a stronger North Korea: Should relations between South Korea and Russia take a turn for the worse, Russia could begin to provide North Korea with significantly more military-technical aid. In particular, Moscow could send Pyongyang military technology such as submarines, ballistic missiles and communications equipment; and, in extremis, nuclear weapons.

The US reaction: It is unclear how sending South Korean intelligence operatives, consultants and propaganda specialists to Ukraine might affect Seoul’s key relationship with Washington. While the outgoing Biden administration would look favourably on this, Donald Trump’s reaction is hard to predict.

Seoul can see that President-elect Trump wants a swift end to the war, and appears to have a very different approach from President Biden to the question of support for Ukraine. South Korean actions in support of Ukraine could potentially cause annoyance, particularly since Trump already has a negative attitude towards South Korea.

As a result, South Korea will be very cautious in its relations with Ukraine, and will send weaponry only if Seoul believes that it has proof that Russia is providing North Korea with sensitive technology which puts the country in danger.

Conclusions

The Kremlin’s decision to call on North Korean troops to support its war against Ukraine is a significant development. It has brought into play a new East Asian dimension to the war and introduced a complicating factor in Russia’s relations with China.

There is no doubt that the appearance of North Korean soldiers in Kursk Region was a factor that contributed to the Biden administration finally allowing Ukraine to use Atacms missiles to strike targets on Russian territory. Ukraine had been asking Washington for months to provide a green light but the White House prevaricated for fear of escalating the war.

From a US perspective, the arrival of North Korean troops was a serious escalation by Putin and was designed to signal Russia’s ability to put pressure on US allies in other parts of the world. This was a step that could hardly be ignored by South Korea, for example..

10,000 North Koreans on the battlefield will clearly not influence the outcome of the war in military terms. Leaving aside its competence, the contingent is too small to make a serious difference.

Their deployment is part of a broader game that the Kremlin is playing that is heavily influenced by its conviction that the West is rapidly losing its capacity to preserve the global system of governance that it shaped after 1945 and dominated after 1991 when the USSR collapsed.

Russia is not just fighting in Ukraine. In parallel, it is working hard to exploit western weakness to achieve its strategic goal of re-shaping the international order to its advantage.The increased involvement of North Korea, the pariah state par excellence, in Russia’s war against Ukraine is more than it appears. Pyongyang’s enhanced role for Russia is a reminder that the Kremlin has taken its struggle with the West to a higher level far away from the Ukrainian battlefield.