Many experts believe that the war in Ukraine has necessitated a substantial increase in Russian military spending, which increases the instability of the economy and is about to lead Putin to end the war for economic reasons. This analysis shows that these concerns are greatly exaggerated.

Executive summary

- Although Russian military expenditures have more than doubled compared to the pre-war period, nearly half of this increase has been directed towards household payments, helping to sustain aggregate demand.

- During the war, the Kremlin significantly increased the utilisation of available production capacity within the military-industrial complex (MIC), but it has not undertaken mobilisation efforts comparable to those seen in the United States during the Second World War.

- A moderately tight fiscal policy, strict control over the budget deficit, and the Bank of Russia’s ultra-tight monetary policy have enabled the Russian economy to maintain inflation at around 10% per annum. If the war ends, the Kremlin is likely to sustain current levels of military expenditure on arms and ammunition for an extended period.

Limited war, limited expenditures

For the Russian economy, the war in Ukraine is of a limited nature. Although the line of contact is more than 1,200 kilometers, starting from the summer of 2022, at any given moment, the military actions are concentrated in narrow areas and barely touch Russian territory. The troops deployed in Ukraine number 700,000–750,000, 0.5 per cent of the country’s population. Of course, even a limited war has required a significant concentration of financial resources; however, Russian spending on the war is not excessively high.

Russian budget expenditures, identified in the budget as ‘National Defence’ increased from three per cent of GDP in the pre-war years to 6.1 per cent of GDP under the budget law for 2025. At the same time, the increase in military expenditures did not lead in 2023–2024 to a decrease in spending on social items of the federal budget, because it was financed by increasing the direct and indirect tax burden on the economy. On the one hand, the Kremlin raised various taxes annually, which brought 0.5–0.7 per cent of GDP per year to the Treasury. On the other hand, the government used previously accumulated fiscal reserves and received significant inflationary revenues, including revenues from the revaluation of the government’s foreign currency assets due to rouble devaluation.

The favourable situation on the world oil market allowed the Kremlin to keep the budget deficit at less than two per cent of GDP in 2023–2024. Although the Russian government (directly or through state-owned companies) controls banks that accumulate almost 80 per cent of the banking system’s assets, which makes it possible, if necessary, to channel national savings to finance the budget deficit over the past three years, this possibility has been used in insignificant amounts. In other words, this represents the Kremlin’s reserve.

The significant redistribution of financial resources in favour of unproductive expenditures expectedly led to a loss of equilibrium, which resulted in higher inflation rates – cumulative price growth since the start of the war has exceeded 35 per cent. However, this is not unusual for Russia: the accumulated inflation rate in 2011–2020 amounted to 84 per cent (6.3 per cent on average per year). The slowdown in inflation at the end of spring 2025 is not sustainable, as it results from deflation in the non-food product segment caused by the strengthening of the rouble.

What do the statistics see?

About 40 per cent of Russia’s increase in military expenditures above the pre-war level (1.25–1.3 per cent of GDP) was spent on payments to servicemen and their families. Although these expenditures do not create long-term economic potential and human capital, from the point of view of macroeconomics, they are similar to any social payments from the budget to the population, i.e. they maintain aggregate demand.

The Kremlin’s total expenditures on warfare, not related to payments to households (purchase of arms, ammunition, medicines, fuel, food, etc.), do not exceed 2 per cent of GDP, which confirms the limited nature of the use of the economy’s potential for warfare. This may have two explanations. Perhaps the Kremlin consciously limits spending on war to the level of minimum sufficiency or the production potential of the Russian military-industrial complex (MIC) is used to its full capacity, but this capacity is minimal. The second hypothesis is more likely.

The Kremlin’s original war plan envisioned a blitzkrieg with no more than a month’s lead time, which did not require the preemptive increase of current production to build up weapons and ammunition stocks. This task arose in mid-2022 when Putin decided to move to a war of attrition. Within nine months, Russian MIC companies that produced weapons and ammunition for the war in Ukraine switched to working three shifts, sometimes seven days a week. By mid-2024, the number of people employed in the MIC had grown to 3.8 million, up from two million before the war.

The nature of warfare and the Russian army’s demand for armaments changed rapidly during the war: the use of tanks turned out to be much less effective than the generals had hoped; more artillery and shells were needed for offensive and defensive actions; the appearance of drones forced Russia first to import them from Iran, and then to launch its own production. In addition to battling drones, the MIC designed and started to produce electronic warfare instruments. In the absence of modern aviation in Ukraine, glide bombs, which the MIC modelled on the American ground-launched small diameter bombs (GLSDB) and launched into mass production in the first half of 2023, proved highly effective in overcoming defensive lines.

By the summer of 2023, the MIC’s capacity to increase production was exhausted, which was reflected in the stagnation of the industrial output at that time. By the end of 2023, the MIC was able to build and launch several new production facilities (mainly for drones and electronic warfare equipment), which resulted in the accelerated growth of industrial production and the economy.

Russian statistics carefully conceal all the MIC’s performance information, so all estimates are illustrative. The most interesting is the graph constructed by the Centre for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-term Forecasting (CMASF), created by the now Minister of Defence Andrei Belousov, which obtained the most detailed information on the performance of the Russian industry. Its graphs show the dynamics of the entire industry, including MIC (red and yellow lines), and the dynamics of the industry from which sectors with a high share of defence products are excluded (blue and green lines).

Russian industrial output according to Rosstat data, and estimates by CMASF and HSE

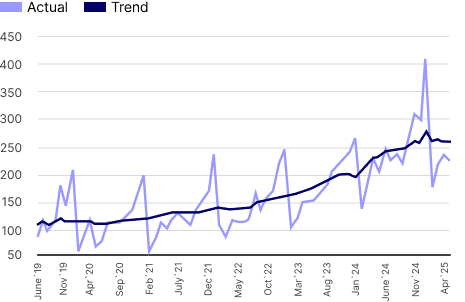

In addition, the CMASF shows the production dynamics in the industrial sectors with a high share of defence products, which gives an indication of the MIC’s production intensity.

Manufacture of ready metal products apart from cars and equipment

Manufacture of other transport means and equipment

Manufacture of computers, electrical and optical products

Those charts show the first wave of military production growth over the first half of 2023. For this purpose, the MIC had to recruit additional employees and switch to a two- or three-shift operation mode. The second wave of military production growth started at the end of 2023 and its potential seems to be coming to an end this spring. The growth was associated with the launch of new industrial facilities that do not require significant investments and sophisticated equipment. Although it has proved impossible to find statistical evidence that the Russian authorities forced private companies to reduce civilian production in favour of increasing military production, such a policy may have existed in a limited form.

How sustainable is military spending?

Can Russia continue to finance the war at current levels, and if so, for how long? Given the limited spending on arms and ammunition, the Russian budget will not be seriously strained if the Kremlin continues the war for another year or two. Inflation – the main indicator of economic disequilibrium – may rise, but if the budget deficit is constrained at the current level, the increase in price growth will be moderate.

The most serious challenge for the Russian economy by early summer 2025 is not the inflation rate but the recession in non-military industrial sectors, caused by the Bank of Russia adopting a tight monetary policy. From mid-summer 2023, the central bank consistently raised its key rate which reached 21 per cent by November 2024. The logic behind the monetary authorities’ actions was ambiguous: price growth was driven by higher military outlays and a redistribution of resources – factors the interest-rate hikes could not influence. Instead, the increase in the interest rate led to a rise in the cost of bank loans and leasing payments, which put severe pressure on the civilian sectors of the economy. The government’s decision to stop subsidising mortgage interest rates exerted additional pressure on economic activity, causing a downturn in construction and building-materials production. As a result, at the turn of 2024 and 2025, statistics recorded a sharp slowdown in the economy – GDP growth in the first quarter of this year amounted to 1.4 per cent against 4.3 per cent in 2024.

The slowdown in growth led to a reduction in inflation tax, while the rouble strengthening led to a fall in oil and gas revenues. This combination came as an unpleasant surprise to the Russian budget, and the government had to introduce, so far minor, spending cuts. There is no reason to believe that the Ministry of Finance will not be able to finance the current year’s budget expenditures. Still, if the economy does not return to higher growth rates, the need to cut non-military spending may become more stringent when planning next year’s budget. There is no doubt that Putin’s economic team can convey to him the nature and magnitude of the problems in the economy, but he now considers them manageable and within bounds. It is impossible to imagine a combination of economic difficulties that would cause the Kremlin to abandon the war.

What about the post-war future?

Over three years of war, the Russian army has gained unique experience in conducting military operations using a wide range of weapons. Undoubtedly, this experience will be carefully studied and analysed by Russian military planners. Based on the conclusions drawn, the decisions will be made on the prospects or lack thereof for individual systems, the need for minor improvements or significant modernisation of existing systems, or the creation of fundamentally new ones. It would be naive to think that any expert today can foresee how quickly and in what quantities new weapons systems will enter the Russian army.

Meanwhile, the Russo-Ukrainian war is asymmetrical in the weaponry available to the two sides. The Russian military has almost all types of offensive weapons in its arsenal. At the same time, the Ukrainian army is limited to the types and quantities of weapons supplied by its western partners. Ukraine’s arms production, except for drones, lags far behind the army’s needs. For example, because of the lack of modern aviation, ballistic missiles, and a sufficient number of long-range missiles in the Ukrainian military, the Russian army did not face any contest for air superiority over its own territory.

In the scenario of a stable ceasefire, restoring economic growth will remain a significant challenge for the Russian authorities. Since Russia did not carry out economic mobilisation after the outbreak of the war and did not restructure civilian enterprises to produce military goods, the key constraint on economic activity will be the lack of available production capacity. Before the onset of the industrial recession (end of 2024), Russia’s capacity utilisation rate was 75 per cent in manufacturing and 82–85 per cent in retail and services. Reducing defence procurement will free up some production capacity. However, it cannot readily be converted to non-military production.

To increase industrial potential, the economy needs to build new facilities requiring new equipment and technology. European countries traditionally supplied equipment and technology to the Russian economy. Yet, economic relations with Europe have been frozen since the beginning of the war, and even if European sanctions are removed gradually, the technology transfer to Russia will hardly resume in a short time. Increased trade with China and imports of machinery and equipment from that country allow Russian companies to maintain and modestly modernise existing facilities. However, direct investment from China in Russia is insignificant in volume and concentrated in the commodities sector’s projects that involve exports to China. Such a scenario for Russia would mean low growth rates and a gradual widening of its technological gap with advanced countries.

Conclusion

Assuming that Western technological sanctions remain in place and China will not provide Russia with access to its advanced machine tools and AI-related technologies, Russia’s role in the latest ‘revolution in military affairs’ will be limited. But this does not mean that the Kremlin will be unable to maintain the current level of military spending (deducted payments to households). The MIC’s products used by the Russian army do not require the latest technological advances; the production of most of the imported components began 10–15 years ago and is located in countries that have not joined the sanctions alliance.

The inability to import modern technological equipment will constrain the MIC’s ability to create and produce more modern weapons. Yet as the war in Ukraine shows, Russian generals and politicians believe that land warfare without the use of nuclear weapons can still be fought using old methods.