In 2024, Russia’s political system became more personalised, centralised, and dependent on loyalty over competence. Power has consolidated under the ‘President Writ Large’, while elite renewal stalled and social mobility narrowed. The regime is now preparing for long-term confrontation with the West and a managed generational transition.

Introduction

2024 was an eventful year. Both the Russian regime and the way it interacts with society – in fact, the entire political system – experienced significant changes in 2024 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Russia and the world in 2024. Timeline

The transformation was gradual in nature, reflecting the continued evolution of trends that first emerged in the spring of 2022 after the start of the full-scale war against Ukraine, as well as earlier impulses from 2020 – the constitutional reform (launched with Putin’s speech on 15 January) and the pandemic (marked by his televised address on 25 March).

The most significant developments and acceleration can be observed in the following socio-political phenomena (see Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Shifts in the political system along key vectors in 2024

- Personalism and substitution. The ‘President Writ Large’ has grown stronger against the backdrop of continued institutional weakening and the decline of the main elite clans. Putin-the-leader is increasingly distancing himself from his old associates and relying more and more on personally loyal servants.

- State seizure of private property. Requisitions have intensified, with open disregard for property rights and the rule of law on the part of the president, the Prosecutor General’s Office, and the judiciary.

- Closed-loop personnel policy. The Putin model appears to have exhausted its capacity for leadership renewal, while the upper ranks of the system are ageing. There has been a sharp expansion of the institute of ‘overseers’, increasingly staffed by members of the president’s ‘extended family’.

- Shifts in the elite balance. Business is under pressure, corporate pyramids are being dismantled and integrated into a single structure.

- Reshuffling of social strata and decline in social capital. Since the start of the war, there has been a visible reconfiguration of social layers, while social capital has been in decline at least since 2020. This includes the downgrading of younger and more Westernised segments of society, as well as a widening gender gap in income and status.

At the same time, the following trends remain largely unchanged:

- Continued centralism and centralisation

- Repression directed at members of the elite

- The consolidation of society.

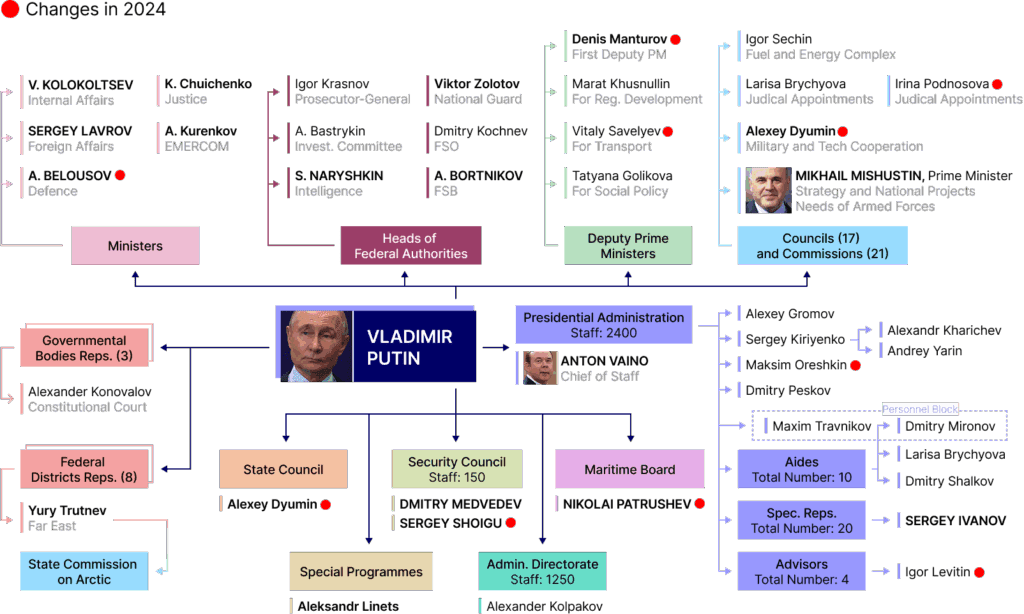

As a result of the transformation of 2024, the system has become more personalistic. Institutions are no longer functioning independently; they act only when directed by the ‘President Writ Large’ – the expanded structure of presidential authority that encompasses the presidential administration, the State Council, the Security Council, and various other councils and commissions under Putin (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. President Writ Large

The ‘President Writ Large’ expanded further in 2024, with the reorganised Maritime Board, the Federal Biomedical Agency, and the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation all transferred from the government to presidential oversight. New directorates have appeared within the makeup of the administration: for state policy in the humanitarian sphere, in the sphere of the military-industrial complex, and others.

Personalism has intensified as well in the public sphere: the war provided Putin with a dominant position in the view of the security bureaucracy, social conservatives, and, what is especially important, the ‘losers’ in the process of modernisation – skilled and unskilled industrial workers and the technical intelligentsia. Putin himself places particular trust in the veterans of the ‘special military operation’, but it is too early to speak of them as a fully formed social group.

If Russian society suffered from insufficient social mobility throughout all of the 2000s, the start of the war switched on the social elevators. Broad career opportunities are opening up for those who are ready to fight, are needed by the war economy, are loyal to the regime, and do not entertain any democratic illusions. The urban educated class – participants in and supporters of modernisation – have found themselves on the sidelines.

Besides, a qualitative transformation of power is taking place. The Russian regime has worked out a strategy, and has begun its implementation in two directions:

- Preparation for a prolonged standoff with the West.

- Preparation for the transfer of power to a new generation of leaders – to the ‘older grandchildren’ over the heads of the ‘children’.

Although the regime as a whole has aged, relatively young individuals – by the standards of the bureaucratic system – are being appointed to key positions in state institutions, despite lacking substantial management experience. For example, 38-year-old Anton Alikhanov has become the minister of industry and trade, and 39-year-old Dmitry Bakanov is now the head of Roscosmos. Promoting youth to positions that they will ‘grow into’ is a widespread model for authoritarian regimes. On the one hand, it ensures a nominal change of managers, while on the other, it delays real change by 5–10 years. At the same time, political competition within the system is also declining: the younger cohort is still preparing for it, while the middle generation of leaders has been stripped of any real prospects.

About the index

The political transformation index is our first attempt at a comprehensive assessment of the transformation of the regime and the start of a large-scale, regularly updated monitoring project.

The Putin regime is unique by its nature, and we have decided not to restrict ourselves to the idea of end-to-end transformation, for example along the democratic/authoritarian axis. The aim of our project is to analyse the multi-faceted transformation of Russian society and the Russian state as a dynamic, evolving process.

The index is calculated annually and consists of a set of scores along a system of vectors pointing to specific shifts. These vectors are:

- Personalism – functional substitution. Tracks the degree of personalisation in governance.

- Centralism and unitarism. Measures the degree to which power is centralised on the federal executive level, with reduced autonomy for regions and institutions.

- Horizontal redistribution of power. Assesses changes in the balance of power across state structures – whether coordination bodies are gaining or losing influence relative to one another.

- Repression: the elites. Monitors the scale and frequency of repressive measures targeting elites.

- Repression: society. Captures the extent of state coercion against broader society.

- State seizure of private property. Reflects the level of state encroachment on private economic assets – through nationalisation, forced transfers, or informal pressure.

- Political elite renewal. Measures whether and how new personnel enter the ruling class.

- Dismantling the patronage and institutional pyramids. Tracks changes in the structure of power hierarchies, including patronage networks and institutional pyramids.

- The state of society. Evaluates shifts in social cohesion, trust, inequality, and public engagement – as well as the emergence of new privileged or marginalised groups.

- Conflicts within the elites. Captures signs of intra-elite rivalry, competition for influence, and shifts in the informal balance of power.

- Decision-making. Assesses the visibility, transparency, and structure of political decision-making.

- The shadow of war. Measures how the war affects domestic politics.

Each of these vectors is assessed using the following scale:

- 0 – absence of changes

- 1 – limited development of previously formed trends

- 2 – substantial development

- 3 – radical change.

If a process is moving in reverse, the same scale is applied with a negative sign.

Analytical comments with respect to each of the vectors provide the rationale for our scores and offer an expanded picture of what is taking place. The scores for each of the vectors are re-evaluated on a regular basis as the situation develops, and supplemented if needed. The vectors of the index are calculated on the basis of instrumental parameters or, where possible, on the basis of expert assessments.

This summary index will be followed by a series of thematic reports on the key directions, to be published separately. The base index offers a snapshot of the situation at the end of 2024, with selected updates from the first half of 2025 included where relevant.

Personalism – functional substitution

The personalistic character of the Putin regime has intensified significantly over the past five years: since 2020 (the constitutional reform), and especially since 2022 – after the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine. The most significant event of 2024 in this context was the presidential election.

The first elections under the new (Putin) Constitution symbolised the transition to a consolidated dictatorship with the weakening of all political institutions except the presidency, and of all elite clans besides Putin’s ‘extended family’.

In the 15–17 March election, Putin secured 87.3 per cent of the vote, with an official turnout of 77.5 per cent. Three little-known candidates were permitted to participate as nominal opponents. The effective number of candidates in 2024 was 1.3, down from 1.65 in the 2018 elections. This indicator reflects not just how many candidates ran, but how evenly the votes were distributed among them – a lower number means less real competition and a more dominant frontrunner.

As early as 2014, Putin’s legitimacy began to rest less on electoral success – that is, winning competitive elections – and more on his image as the nation’s leader or chief. This role was further reinforced in 2022 with the outbreak of war and his assumption of the role of supreme commander-in-chief. A chief, by definition, does not compete seriously in elections – he cannot have credible opponents, as that would undermine his very status.

According to Levada Center data, the level of trust in the president in 2024 increased noticeably compared with 2023. 80 per cent of respondents had complete trust and a mere 5 per cent did not trust Putin – against 76 per cent and 8 per cent a year earlier. The presidency remains the only powerful institution in Russia, continually consolidating authority at the expense of all other institutions without exception. As a result, confidence in institutions in general diminishes, as does their role.

The raw results of social surveys do not provide a complete picture, as they are influenced by the ‘halo effect’ – where trust in the president is partially transferred to other institutions. The relative trust in these institutions, expressed as a proportion of the trust placed in the president, is as follows:

- The army – 0.86

- The state security organs – 0.79

- The church – 0.73

- The government – 0.71

- Regional authorities – 0.6

- The State Duma – 0.59

- The courts – 0.51

- Big business – 0.39.

The annual 100 Leading Politicians of Russia ranking by Nezavisimaya Gazeta offers insight into the broad contours of the Russian ‘Olympus’ – one that is more administrative than political in nature. In 2024, against the background of large-scale personnel reshuffles, 550 changes were recorded in the rankings of specific persons (against 492 in 2023) and 571 changes in job positions (against 476 a year earlier). The example of the Security Council secretary illustrates clearly that influence in Russian politics depends more on the individual than on the position itself. In 2023, this position was held by Nikolai Patrushev, and he was ranked 7th in the influence rating. In 2024, despite holding the very same position, Sergey Shoigu was ranked 31st.

The ‘extended family’, including Putin’s relatives, the children of his associates, as well as aides, bodyguards, and university classmates, accounts for over 40 per cent of the appointments to top positions in 2024. The overall influence rating of the ‘President Writ Large’ increased from 111 in 2023 to 139 in 2024. It had comprised 21.4 per cent of the sum total in 2023; in 2024 this figure was 24.3 per cent.

Elite clans

Elite clans are being weakened as institutions erode, since clan influence is exercised – in one form or another – through formal and informal institutional structures.

In Yury Kovalchuk’s clan, for example, the erratic career path of his son Boris is particularly telling. After stepping down early as head of the energy company ‘Inter RAO’, he passed briefly through the Presidential Control Directorate before becoming chairman of the Accounts Chamber. Formally, it is a high-ranking position – in reality, an honorary retirement at not quite 50.

A blow from the authorities also struck the clan of Igor Sechin, a situational ally of Kovalchuk. Sechin – chairman of the board of directors of ‘Rosneftegaz’ – failed miserably in the development of ‘Vostok Oil’, breaking a promise made to Putin. Besides, Sechin was unable to handle problems with shipbuilding – this sector had to be handed over to Andrey Kostin (VTB bank) and Nikolai Patrushev (the Maritime Board).

The head of yet another clan, Sergey Chemezov, could not handle another important matter – civilian aircraft manufacturing, which provoked Putin’s fury and led to the resignation of the heads of the United Aircraft Company (UAC).

Mikhail Mishustin demonstrated technical efficiency as head of the government, but ran into a humiliating delay during the official announcement of his candidacy for a new term. Mishustin also lost part of his team.

Sergey Kiriyenko came out more a loser than a winner during the formation of the new presidential administration (PA). In particular, he lost control over the State Council.

Moscow mayor Sergey Sobyanin survived the year without significant losses and even acquired a controlling stake in the leadership of ‘United Russia’ (UR) through his protégé Vladimir Yakushev.

Functional substitution

During all the years of Putin’s rule there has been a steady reduction in the role of relatively independent political institutions, and their replacement by substitutes – functional analogues under the control of the president, deprived of direct legal capacity. Examples of this are the State Council, the Security Council,and other kinds of councils the Accounts Chamber, and commissions under the president. The list of positions in these substitutes already numbers in the hundreds, and the growth of this list is starting to slow naturally.

The activity of the political parties, the Central Electoral Commission, and the structure of ‘independent observers’ (most of whom are, in fact, state-aligned) around the 2024 presidential elections can serve as an example of the weak individual agency of institutions. According to the script prepared by the presidential administration, only three candidates approved by the Kremlin were able to ‘compete’ with Putin – and these were not even the strongest representatives of their respective parties.

The clearing of the political stage continued under the label of ‘foreign agent’ – a modern echo of the Soviet-era term ‘enemy of the people’. On 15 May 2024, a federal law was adopted prohibiting foreign agents from running for office in elections, from being observers at elections or candidates’ agents and their authorised representatives. As a result, three deputies to the Moscow City Duma received the status of foreign agent in Russia and lost the right to be elected anew to the city parliament. Several regional and local deputies lost their mandates.

In the case of substitutes, three main points of their growth emerged in 2024:

- New directorates in the presidential administration, transforming it into a de facto analogue of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, as it increasingly duplicates the functions of the government.

- The Maritime Board under the president with three councils: for strategic development of the Navy (Nikolai Patrushev); for defence of the national interests of the Russian Federation in the Arctic (vice-premier and presidential envoy Yury Trutnev); for development and support of the maritime activity (head of the Presidential Directorate for National Maritime Policy Sergey Vakhrukov).

- The ‘Time of Heroes’ personnel programme – a specialised initiative for participants in the war in Ukraine, aimed at training new civil servants and shaping a new elite.

Putin’s system of placing ‘overseers’ from his extended circle at the helm of ministries and agencies has gained renewed momentum. These people are Irina Podnosova (Supreme Court), Alexey Dyumin (State Council and the defence complex), Anna and Sergey Tsivilev (Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Energy), Valery Pikalev (Federal Customs Service), and Boris Kovalchuk (Accounts Chamber).

With the replacement of its secretary (Shoigu for Patrushev), the Security Council has likewise lost relative independence. A similar situation can be observed with the Accounts Chamber and the State Council. The replacement of not only the entire leadership of ‘United Russia’ but also its model of governance – shifting from a politico-public structure to a purely bureaucratic one – has led to a marked weakening of the party.

The composition of many presidential councils and commissions has been refreshed, including that of the Commission for Strategic Development of the Fuel and Energy Sector and Environmental Security – of paramount importance from the point of view of state budget revenues. Igor Sechin remains the executive secretary of the commission. Its new composition brings together executives from oil and gas companies and state corporations, government officials, academics, and members of the security services. The commission’s working groups – one focused on the fuel and energy sector (FEC) itself, the other on improving efficiency and transparency within FEC companies – are chaired by ‘Zarubezhneft’ Director General Sergey Kudryashov and FSB Deputy Director Sergey Korolev, respectively.

At the regional level, the system of ‘party’ governors – in place for over a decade – continued to be dismantled. The governors of Smolensk and Omsk Regions were replaced in 2023, followed by the governor of Khabarovsk Krai in 2024. As a result, the LDPR party lost its sole representative in the governors’ corps, while ‘A Just Russia’ now counts one governor in its ranks instead of two.

The Kremlin’s long arms have even reached down to municipal organs of power, which had faded into the deep background with the start of the full-scale war. In 2025, Putin signed a law that formally eliminates nationwide elections of mayors – they are now going to be appointed by governors. The principal work on this law had been carried out back in 2024.

Score: 2 – substantial development

- There was significant growth of the regime’s personalistic features – a trend reinforced by the war, the presidential elections, and the ageing of Putin-the-leader, who is distancing himself from old associates and increasingly relying on loyal servants.

- De-institutionalisation continued, enabling short-term crisis management – but also heightening the risk of institutional paralysis.

- The leadership of key ministries and agencies saw a sudden and substantial influx of Putin’s personal overseers.

- The presidential administration began rolling out institutional substitutes aimed at integrating participants in the war in Ukraine back into civilian life.

- Institutions connected with elections and local self-government grew weaker.

Centralism and unitarism

Russia is a country that is de facto unitary and centralised beyond measure. Nevertheless, during the pandemic – and even more so during the war in Ukraine – the system required flexibility and the capacity for swift action. While Moscow delegated certain powers to the regions to manage urgent challenges, it retained centralised control over the distribution of resources.

During the time of the war, the regions were supposed to produce ‘volunteer battalions’ and keep supporting them with fresh personnel and ammunition, on the Kremlin’s orders. The responsibility for supplying personnel for the regular army rests on the regions’ shoulders as well. In addition, the regions are expected to take cities and districts in the occupied Ukrainian territories ‘under their wing’ – providing them with financial and staffing support, as well as equipment and personnel.

The lack of regional independence or political weight is reflected as well in the expert rating of top 100 leading politicians of Russia. There are only seven representatives of the regional elite, and not a single municipal politician.

Moscow mayor Sergey Sobyanin was the only regional figure to appear among the top five most trusted politicians, according to Levada Center surveys. Trust in Sobyanin hovers in the 3–5 per cent range nationally (presumably, in Moscow his trust levels are much higher). The last nationally recognised municipal politician was Sardana Avksentyeva, former mayor of Yakutsk (2018–2021), deputy head of the ‘New People’ party faction in the State Duma. As of now, directly elected mayors of regional capitals remain only in three cities across Siberia and the Russian Far East: Abakan (Khakassia), Anadyr (Chukotka), and Khabarovsk. In Buryatia and Yakutia, direct election of mayors of regional centres was abandoned in 2024.

According to the new Putin edition of the constitution, local self-administration has ceased being a stand-alone power – it now forms the lower tier of public (read: state) power. That said, adoption of the corresponding law on organs of local self-administration was stalled all three years of the war due to resistance from some of the regions’ authorities. Stalled for all three years, the draft law proposed at the end of 2021 was finally adopted only at the start of 2025.

The original plan to unify the two-tier system of local self-government into a single level – as already implemented in some regions – fell through, forcing the Kremlin to compromise by leaving the final decision to the discretion of individual regions. As a result, Tatarstan publicly objected to the initial draft of the reform. It is worth noting that Tatarstan occasionally plays the opposite role – serving as the initiator of legislative proposals at the behest of the central authorities.

On the whole, administrative, political, and financial control over the situation in the regions remains in the hands of the Kremlin. No cracks in the monolith of Russian unitarism can be observed.

The campaign to replace local heads of regions with outside appointees, actively launched in 2018, appears to have come to an end. In 2024, the heads of ten regions, including five taken into the federal government and the administration of the president after an ‘internship’ in the regions, were replaced according to the ‘like for like’ principle: outsiders were replaced by other outsiders, while locals were succeeded by local figures.

Of the five governors who had been transferred to ministerial posts in Mishustin’s new government, four had been parachuted into the regions from the federal government and the State Duma in the last cycle of replacements. Only Sergey Tsivilev transitioned into a governorship from the business sector – but as the husband of Putin’s first cousin once removed, and a member of the president’s ‘extended family’, he occupies a unique position.

From the Kremlin’s point of view, the regions are the territorial subdivisions of a single unitary corporation. Work experience in these ‘subdivisions’ is useful, but not mandatory. In 2024, the Kremlin replaced 13 heads of regions: eight in the spring within the framework of the pre-election rotation, and five in the autumn. Five of the springtime governors, who had served a full first five-year term or had begun a second, were summoned to Moscow – as ministers into the government and into the presidential administration. All of them had in their time been sent to the regions from the federal structures and had gone through the informal ‘school of ministers’.

The case of Samara Region governor Dmitry Azarov, elected a year earlier to a second term, is unusual. Thanks to the joint efforts of siloviki [security agencies] and the Kremlin’s political bloc, Azarov proved unable to form a team, as key appointments were blocked or imposed from above. In the autumn, a similar incident took place in Kursk Region, where the Kremlin replaced a governor who had taken up the position half a year before and had been officially elected several weeks prior to his dismissal.

While the 2018–2020 cycle saw an active replacement of local elites with Moscow-appointed bureaucrats in the governors’ corps, the current approach appears more cautious – particularly with regard to troubled regions. New governors have stronger regional ties than their predecessors did (see Table 2).

Table 2. Regional leadership turnover in 2024: profiles of outgoing and incoming governors

In the development of the new national projects for 2025–2030, regional governors took part in the work of project committees – appointed as deputy heads in their capacity as chairs of the relevant State Council commissions. Their involvement might not have played a big role, but symbolically it was important. When the adoption of the programmes started to fall behind schedule, Putin reminded the government of the need to provide the regions in a timely manner with specific milestones relating to the national projects as well as the corresponding funding.

Particularly noteworthy is the appointment of public-facing politicians as heads of Vologda Region (Georgy Filimonov), Samara Region (Vyacheslav Fedorishchev), and Kursk Region (Alexander Khinshtein). All are outside appointees and populists; that said, their populism is directed not against the central authorities, but against local oligarch businessmen. Andrey Turchak, the only federal-level politician to take up a regional post, was appointed governor of the Altai Republic; he no longer plays a public role in federal politics.

Contributing as well to regional consolidation is a growth in the regions’ financial dependence on the centre, and a reduction in regional contrasts. If a flattening out towards the middle is taking place in economics, then in politics it is a flattening towards the bottom.

According to the ‘Expert RA’ rating agency’s data, the share of inter-budgetary transfers in 2024 fell to 17.3 per cent – this is 2.7 percentage points lower than in 2023. The reduction can be explained by an increase in the regions’ own tax and non-tax incomes (by 13.5 per cent in 2024). Equalisation transfers from the federal budget were received by 63 regions, while 22 regions (excluding the four occupied territories) received none. In 2023, the figures were 62 and 23, respectively.

A serious challenge to the vertical system of territorial administration developed under Putin was posed by events in the second half of last year, when the Ukrainian army seized part of Kursk Region. Neither the local nor regional authorities – nor the emissaries sent from Moscow – were able to function effectively in the emergency. Personnel changes made no difference, nor did the introduction of a hands-on management regime.

Standing alone among the Russian regions is Chechnya. Its leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, has built his own political regime, connected with Putin’s through vassal relations. He combines the positions of a long-time head of a region and chief of his own security structure. Some time ago one could regard him as a federal-level politician, but now it would be more appropriate to see him as a newsmaker.

Score: 1 – limited development of previously formed trends

- The concentration of authority and assets at the very top has reached a level where it cannot grow further, and indeed this would not be in the regime’s interests.

- Since 2020, and especially since 2022, a forced and limited movement toward partial decentralisation has begun: the regime has delegated some of the responsibility for resolving its long-time problems on to the regions.

- Decentralisation, even to such a low degree and accompanied by tight administrative and financial control on the part of the Kremlin, shows the well-known adaptability of the system and increases its robustness.

Horizontal redistribution of power

The executive branch of power has dominated the Russian regime since the end of 1993. The degree of independence of the representative and judiciary branches is directly dependent on the strength or weakness of the Kremlin. Currently, the Kremlin is stronger than ever; it has taken over the administrative, financial, personnel, security and other levers and has obtained tight control over all spheres of the state’s activity. This control, not always formal prior to 2020, was officially enshrined in Putin’s ‘reformed’ Constitution. 2024 can be regarded as a year of continuation of Putin’s constitutional reform.

The fiction of the Duma’s and Federation Council’s new powers concerning the confirmation of the government was demonstrated for the first time. The parliament, naturally, had no influence on the composition of the government, but was merely formalising decisions already adopted by the Kremlin.

Expansion of the ‘President Writ Large’ continued at the government’s expense – ever more government functions are de facto controlled by the presidential administration or by Putin personally.

The de-privatisation and nationalisation of private assets at the behest of the Kremlin has shown a new stage in the deterioration of the judicial power; noticeable repressions in the judicial corps were carried out as a warning.

A law was prepared (and signed by Putin in 2025) abolishing the institution of elected mayors in regional centres – they will now be appointed by the governors. Municipal reform did not end with the complete dismantling of the institution as such – remnants of this level of power have been preserved as a concession to large ethnic republics.

The ‘President Writ Large’ dominates over all branches of power; assessing the redistribution of power between them therefore gets quite difficult. One of the ways of assessing is to trace the representation of officials from various branches of power among the hundred leading politicians of Russia (see Fig. 4).

From the rating, it is clear that the power of the ‘President Writ Large’ has grown stronger at the expense of the government, including that part of it which is directly subordinate to the president; one can also see the relatively insignificant role that the Federal Assembly and the regions play.

The Federal Assembly is represented in the rating by eleven people (hereinafter – ranks in cardinal numbers). These are both speakers – Vyacheslav Volodin (rank 17 in the rating in 2024; 18 in 2023) and Valentina Matviyenko (ranks 22 and 23, respectively), their first deputies, and the heads of the Duma factions. There are one or two top ‘United Russia’ functionaries in both the Federation Council and the Duma. All the senators and deputies taken together account for 10.1 per cent of the total rating in 2024 (11.1 per cent in 2023). Their overall number has fallen as well – from 12 in 2023 to 11 in 2024.

As is traditional, the judicial power is only modestly represented in the hundred influential politicians – by the two heads of the highest courts: the Supreme (Podnosova, 78 in 2024; 79 in 2023) and the Constitutional (Zorkin, 97 in 2024). Higher positions are held by the representative of the president in the Constitutional Court (Alexander Konovalov, 83–84 in 2024; 76 in 2023) and chief of the Main Legal Directorate of the President Larisa Brychyova (55 in 2024; 60 in 2023). Chairman of the Supreme Court Irina Podnosova is a classmate of Putin’s from St Petersburg (Leningrad) University, who ended up on the Supreme Court in 2020 and represents not so much the pinnacle of the judiciary as Putin personally.

The Duma demonstrated a high degree of consolidation in voting in 2024, especially on key issues. The majority of deputies, irrespective of what faction they belonged to, voted identically. Last year, the Duma considered 1,086 legislative initiatives, 564 of which became federal laws. Practically all the government’s draft laws were adopted (their overall number was 265, which comprises 22 per cent of the total number of draft laws). A mechanism for accelerated consideration of the government’s draft laws by the Federal Assembly has been in effect since 2022. This mechanism was not used in 2024, but some important laws, including the law on the budget, were adopted in short time frames.

The shift of certain functions from the government to the presidential institution – notably through the establishment of the Maritime Board and new directorates within the presidential administration responsible for the military-industrial complex was examined in the chapter Personalism – functional substitution.

In the view of experts, the balance between the president’s government and the prime minister’s government has shifted only marginally. In 2023, five members of the government directly subordinate to the president entered into the country’s first hundred influential politicians – their aggregate influence comprised 5.6 per cent of the overall sum for the hundred. In 2024, these same five accounted for 5.3 per cent. There were 19 direct subordinates of the prime minister in the top 100 in 2023; in 2024 there were 18. Their total weight dropped from 18.9 per cent to 18.2 per cent.

Formal discussion of and voting on candidates to become members of Mishustin’s government in the State Duma lasted three days, from 11 to 14 May 2024. Consultations in the Federation Council on the heads of the security agencies, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), and other presidential structures took even less time: 13 May in committees, and 14 May at the plenary session. All the candidates submitted by Putin and Mishustin received full support.

One telling detail illustrates the balance of power between the government and the State Duma. During the formation of Mishustin’s new cabinet in May 2024, three ministers were left without seats in the government. Yet by September, all three had become State Duma deputies through by-elections – and were promptly appointed to senior roles: one as a deputy speaker and two as chairs of key committees.

Repression plays a far from marginal role in shaping the configuration of the presidency, government, Federal Assembly, and the courts. In 2024, it was used primarily as a tool of warning: targeted dismissals and prosecutions affected several deputy ministers, two senators, and the leadership of regional courts – a practice that first emerged in 2023. A criminal investigation is currently underway against a group of individuals from the judicial system in Rostov Region. The FSB has also intervened in neighbouring Krasnodar Krai, where Alexander Chernov – chairman of the Krasnodar Krai Court from 1994 to 2019 – and members of his family are facing charges over breaches of anti-corruption laws.

The situation is different at the regional level than at the federal – above all by virtue of centralism. In the regions, both the judicial power and the representative power are subordinate to a significant degree to the ‘federals’. Business has become a more active player: in many regions, the party branches operate in all but name like franchises – they are run not by party leaders from above, but by local businessmen.

In the regions, the executive power, with support from the federal centre, is gradually taking authority away from the representative organs. The situation is the opposite in the judicial branch: show-trial criminal cases against current and former chairmen of the courts in Rostov and Novosibirsk Regions, as well as in Krasnodar Krai, are aimed at breaking up the close ties between the judicial system, the local executive power, and business.

The course of municipal reform and the revised law on local self-government highlight both the subordinate role of municipal authorities and the ongoing tug-of-war between federal and regional levels over issues the Kremlin does not see as fundamentally important. The draft law ‘On the General Principles of the Organisation of Local Self-Government within the Unified System of Public Authority’ was adopted in the first reading on 25 January 2022. The Duma came back to considering it only in the autumn session of 2024. The second reading was scheduled for 12 December; one day before that, the Council of the Duma decided to postpone consideration of the question to 2025.

The key sticking point was the abolition of city and village settlements in favour of a single-tier system of local self-government based on urban and municipal districts. A new redaction of the law on local self-administration (LSA), granting regions the right to decide for themselves whether to change the two-tier LSA system to a single-tier one, has already been adopted by the Duma, approved by the Federation Council, and signed by the president.

Score: 2 – substantial development

- Executive power grew noticeably stronger following the constitutional reform – above all, the president’s authority; gestures toward the Federal Assembly remained largely symbolic.

- The Kremlin, and Putin personally, tightened their grip on the judiciary at both the federal and regional levels.

- Judges and parliamentarians continued to lose what limited autonomy they once had.

Repression: the elites

The frequency of repressions in relation to the elite rose sharply after 2014 – with Putin’s transition from electoral legitimacy to that of chief – and has been holding steady ever since. The difference is that there are fewer and fewer elite groups left that do not fall under the repressions. If high posts previously provided protection from repressions, the positions of governor (since 2015), federal minister (since 2016), senator (since 2019), and head of a regional court (since 2023) have now been removed from the list of untouchables.

The scope and severity of the repressions or the rationale behind them remained unchanged in 2024. The highest-ranking officials arrested at the federal level were deputy ministers: of defence, energy, and culture. Two senators fell victim to the repressions: a businessman and a former governor; of the ‘regionals’ – two former heads of regional courts were prosecuted.

At the Ministry of Defence, where a personnel purge took place (see Fig. 5), six of minister Sergey Shoigu’s deputies were fired, along with Shoigu himself. Three of the six were taken into custody and are under investigation. They are suspected of receiving bribes. Also under investigation are several Ministry of Defence contractors associated with Shoigu’s deputies.

Fig. 5. Personnel purges in the Ministry of Defence, 2024

The purges in the Ministry of Defence, like the previous time, when minister Serdyukov was fired in 2012, were public and played to sentiments in the military community, for whom the minister and his team remained outsiders. Following the cases brought against Ministry of Defence officials, numerous investigations were also launched into commercial entities linked to them, and subsequently into individuals from Shoigu’s circle in other state institutions. This campaign is likely to spread even further.

No other sector has experienced such a clear concentration of repressive measures as the Ministry of Defence. When it comes to specific positions, however, a wide range of institutions has come under scrutiny: Rosatom, Rosgvardiya [National Guard], the Administrative Directorate of the President, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Digital Development, the Investigative Committee, the Federal Service for the Execution of Punishments, the Federal Protection Service, and others.

There has been a marked increase in repressive actions against former officials – even after a significant time out of office, notably at Rosnano, the Administrative Directorate of the President, the Ministry of Transport, and Rosgvardiya. Repressions against former officials are advantageous in that they create a deterrent effect, but do not destabilise the system.

A clear example is a corruption case dating back to 2009–2014, involving two former deputy chiefs of the Presidential Administrative Directorate, Ivan Malyushin and Sergey Kovalev, as well as the widow of a third former deputy, with 16 other individuals and four construction companies also listed as respondents.

Between 2003 and 2014, Ivan Malyushin was the right hand man of the powerful administrative director of the president Vladimir Kozhin, now a senator from Moscow, while their wives were developing a joint business. The case against Malyushin was initiated back in 2019, was twice dismissed and then reopened anew, and at the end of 2023; he and the other respondents were found guilty. The court ordered them to pay 1.5 billion roubles ($18.5 million), and to forfeit 14 apartments and 118 non-residential properties in Moscow.

It would seem that the misdeed had been punished and justice had triumphed, but at the beginning of 2024 another court began hearing a new case against the 75-year-old former official. This time, it was an issue of exceeding official authority: Malyushin was accused of leasing a parcel of land in the centre of Moscow belonging to the Administrative Directorate of the President to a private firm, the beneficiary of which was a US company. Under the new case, the Prosecutor General’s Office was able to not only achieve recognition of the lease agreement as invalid, but also to transfer the complex of buildings being constructed on the leased land into state ownership.

When posts are taken away from former officials and deputies, this is often framed as serving the geostrategic interests of the state – in practice, this refers to broader political aims such as responding to Western sanctions and compensating for lost export markets through the redistribution of major corporate assets, including in the oil and gas sector, food industry, and others. When Deputy Prosecutor General Igor Tkachev – known for targeting major oligarchs – begins pursuing a 2,500-square-metre plot and an unfinished building, it signals a shift in the rules of the game. Under these new rules, lifetime immunity no longer applies to an official’s freedom or property, remaining in place – and even then, conditionally – only for the duration of their service.

Today, officials and corrupt actors are being offered a form of indulgence: a contract with the Ministry of Defence that includes deployment to the front. In 2024, a law was passed exempting individuals serving in the ‘special military operation’ from criminal liability and punishment. Those not yet convicted but already entangled in the legal system can also take advantage of this option. The war – and the threat of being sent to the battlefield – has become a tool of both punishment and purification.

Among the highest-ranking current regional officials subjected to repressions are 20 vice-governors, the mayors of Astrakhan, Petrozavodsk, and Sochi, and ten heads of territorial structures of the law-enforcement organs (most of all in Sverdlovsk Region and St Petersburg). Here too, repressive measures are mostly directed at former high-ranking officials, rather than current ones. Examples include the former governor of Ryazan Region (2017–2022), the ex-chairman of the Krasnodar Krai Court (1994–2019), and the former head of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) for St Petersburg and Leningrad Region (2012–2019). In addition to St Petersburg, senior MIA officials were also detained in Tula Region.

Purges of regional elites happened most actively in Samara Region, where the governor himself was replaced, as well as in Krasnodar Krai, and in Ivanovo Region. In Omsk Region, repressions followed on the heels of a change of governor. A standard pattern was applied: repressive measures took place both before and after changes in corporate leadership – either pushing for such changes or following them, particularly when protection from powerful patrons had weakened. The most common charges addressed at regional elites were bribes for general patronage, theft during the construction of automobile roads, and organisation of unlawful migration.

Score: 2 – substantial development

- Targeted repressive measures are applied against one segment of the federal elite, while the status quo remains largely unchanged for regional elites.

- The system as a whole finds itself in homeostatic equilibrium with the retention of a relatively stable level of elite repressions.

- Individual bodies, both regional and functional, periodically experience increased pressure – during transition from one state of equilibrium to another, new one.

Repression: society

Paradoxically, during the war years, and in 2024 in particular, the overall repressiveness of the regime has grown but without unleashing the criminal repression machine: the number of cases, both those of a political character and general criminal ones, remains largely unchanged. The climate of fear is instead fuelled by the openness of prosecutions and the performative severity of sentences, with individuals now receiving punishments for social media posts that were previously reserved for active involvement in opposition activity. The authorities are not impeding the dissemination of information about political trials; at times they do not even close the sessions of military courts, and allow the press in. This is the first trend.

The second trend is the diffusion of repressive functions throughout state agencies not directly connected with law-enforcement activity. New laws are being adopted that allow non-criminal and extra-judicial repressions, such as placement on all manner of registers that lead to a restriction of rights (to participate in certain kinds of activity, to dispose of property, to leave the country, and even to drive a car). Educational establishments are expelling students for disloyalty – a call-up to the army is also a powerful tool of repression.

The functions of the system of general criminal law are likewise getting blurred by the emergency wartime order: it is possible to legally avoid prosecution in most general criminal cases by going to fight in the war. Ever more often, criminal charges are being used to pressure individuals considered fit for service into signing contracts with the army. Those who return from war enjoy factual immunity from criminal prosecution, even for violent crimes (this is discussed in greater detail in the chapter The shadow of war).

Political repressions

In February 2024, the opposition leader Alexei Navalny was murdered in custody. According to the data of the OVD-Info information centre, which aids arrestees and collects data on political repressions (here and below we cite the annual report for 2024), another four people arrested for political motives died in places of confinement; yet another two died in investigative jails; one – from the after-effects of being taken into custody.

In 2024, 449 people were given jail sentences for political motives. For comparison: in 2012 there were 46, ten times fewer. In the preceding year, 2023, 429 political sentences were issued.

The average term of imprisonment in politically motivated cases has held steady since pre-war times and fluctuates at around six years. In the times of war, a large part of convictions have been for offences such as ‘public incitement to terrorism’ (the most frequently applied article), ‘spreading false information about the army’, and ‘discrediting the armed forces’. In 2024, people are receiving jail sentences for their words – sentences that, before the war, were typically handed down to active opponents of the regime. By the end of the year, at least 62 well-known journalists and bloggers were in jail.

There are 438 people on the Memorial society’s list of political prisoners, and another 430 on a separate list of those persecuted for religion.

Administrative cases

According to OVD-Info’s data, 3,213 administrative cases were submitted to courts under article 20.3 (Propaganda and Public Display of Nazi Symbols and Symbols of Prohibited Organisations) of the Code on Administrative Offences. Usually targeted under this article are those who publish Ukrainian symbols on social networks, as well as the symbols of organisations prohibited in Russia – those that actually exist (the Anti-Corruption Foundation) and imaginary ones (the AUE – ‘Arestantsky Uklad Edin’, a purported prison-style youth subculture, or the LGBT ‘movement’). The report records 1,199 administrative detentions for participation in peaceful public events, including ones in memory of Navalny.

Foreign agents and other repressive legislation

At the start of the full-scale war, 336 organisations and individuals were entered into the register of foreign agents controlled by the Ministry of Justice. 187 were added to the register in 2022 (nine of these before the war), 187 in 2023, and 204 in 2024. As of the end of 2024, the total quantity of registered foreign agents comprised just under 1,000 individuals and organisations.

Several laws were adopted in 2024 that substantially complicated the situation for foreign agents: the list of grounds for inclusion in the register was expanded, and the rights of foreign agents were restricted – from the right to participate in the activity of various organisations and place advertisements on their own resources to the right to dispose of their own funds. In effect, punishment for disloyalty – typically for regular public statements – has become harsher, while the criteria used by the authorities to place individuals on the register have become even more opaque.

The number of administrative cases opened for not fulfilling the ‘obligations of a foreign agent’ has been rising: 570 in 2024 (223 in 2022 and 441 in 2023). Starting in 2022, a second administrative case in a row leads to criminal prosecution. As of December 2024, a minimum of 32 people have been prosecuted under the article ‘Evasion From Fulfilment of the Obligations of a Foreign Agent’.

Affiliation with ‘undesirable organisations’ can lead to immediate criminal prosecution, and the register of such organisations has been expanding at an accelerating pace since 2015. It is likewise overseen by the Ministry of Justice. In 2024, a record 65 organisations were entered into the register. Globally known media, charitable foundations, and educational organisations are on the list. Hundreds and thousands of people in Russia were connected with each of them – now they all find themselves under threat of criminal prosecution.

The grounds for being entered onto the list of ‘terrorists and extremists’ have been expanded as well – this is done by Rosfinmonitoring [Federal Financial Monitoring Service], likewise by way of an in-house decision, without recourse to a court. Being entered on this list entails not only stigmatisation, but also harsh routine restrictions (for instance, on using a personal bank account).

A whole series of repressive laws restricting the rights of different categories of citizens was adopted in 2024. For example, a law prohibiting childfree propaganda has made public discussion of any difficulties associated with parenthood impossible.

In January 2024, the Supreme Court recognised as extremist the LGBT movement, which does not exist in any organisational forms. Now the police conduct regular raids of clubs – under the pretext that LGBTQ+ events are taking place there. The patrons of a gay-friendly club or an establishment with ‘suspicious’ décor risk being subjected to a document check and administrative detention. Criminal cases are initiated against the organisers of ‘suspicious’ events, and administrative prosecution is in order for ‘LGBT-propaganda’ and displaying of LGBT symbols, including a rainbow.

Repression is intensifying against lawyers and the human rights community, while both factual and legal standards for public statements are becoming increasingly stringent. Laws prohibiting the inflaming of social enmity and offending the feelings of believers and veterans, as well as laws on the protection of personal data are being used to restrict the most varied forms of self-expression. Consequently, videos shot against the background of a temple or a war monument may lead to arrest.

Pressure in the education system is also escalating: children are being required to participate in ideologically-charged activity under threat of punishment; students are being expelled from universities for disloyalty. The school is intruding into the life of the family, requiring children and parents to account for their life and views. Whole layers of everyday practices associated with the life of urban, relatively progressive social strata are falling under prohibition, or becoming risky – from frequenting night clubs to discussing personal life on social networks and shooting videos in public places.

Surprisingly, this clear increase in the regime’s repressiveness has not resulted in a greater number of criminal prosecutions overall, nor in the expansion of law enforcement bodies. On the contrary, repressive functions are diffusing throughout the entire state apparatus, and are not concentrated in the criminal justice system.

Score: 1 – limited development of previously formed trends

- There has been a moderate increase in pressure - driven primarily by extrajudicial persecution.

- Law enforcement bodies have succeeded in maintaining stable performance indicators.

- Criminal repressions are not increasing in quantitative terms – that said, political repression is increasingly concentrated on socially active and stigmatised segments of the population.

State seizure of private property

The redistribution of property, carried out with open disregard for private ownership rights – which the authorities treat as their own, in keeping with Soviet tradition (‘the state giveth, the state taketh away’) – represents a particularly significant trend in political development. It is not only the scale of the property being requisitioned that matters (with more likely to follow), but also the complete subordination of those owners who have not yet lost anything to the bureaucratic apparatus. On the one hand, business, including private business, is reckoned to be a part of the Putinite bureaucracy, but on the other, it finds itself in an even more subordinate position with respect to the authorities.

The total value of the assets seized in 2024 by the state from Russian business comprised no less than 900 billion roubles ($11.1 billion), which exceeds the value of the assets seized a year earlier by a factor of two. The Moscow Times assessed the volume of nationalised property at 483.5 billion roubles ($6 billion), while Novaya Gazeta Europe and Transparency International estimated it at approximately 360 billion roubles ($4.4 billion). This refers specifically to assets seized by the state through court rulings. The value of the assets expropriated to the benefit of public officials is probably an order of magnitude higher than the official numbers.

The issue is not the price of the assets, but the open violation of the law by the president, the Prosecutor General’s Office, and the courts. For example, at the beginning of the year an accident took place at the heating plant of the Klimov Ammunition Factory outside Moscow, which was providing heat to a large residential district. Having found out that the owners were abroad, Putin gave the order to nationalise the enterprise – without getting into details. The enterprise was transferred to Rostec, which had held a minority stake in the company prior to the incident. This egregious case revealed the state’s attitude toward private property and how related decisions are made.

Another major example – involving Rolf, Russia’s largest automobile dealer (with 78 showrooms and 20 dealer centres nationwide) – unfolded in a manner similar to the Yukos case, with one key difference: Rolf’s owner, Sergey Petrov, was abroad and beyond the reach of Russian law enforcement.

Pursuant to a claim by the Prosecutor General’s Office, in February 2022 a court imposed recovery from Petrov into the budget of 19.4 billion roubles ($240 million) – supposedly obtained unlawfully, ‘during a time of combining parliamentary [Petrov had been a State Duma deputy in 2007–2016] and commercial activity’. In December 2023, Rolf was transferred by presidential edict into temporary management by Rosimushchestvo [Federal Agency for State Property Management], and less than a month later, on 15 January 2024, the Prosecutor General’s Office filed a claim in court for the nationalisation of Rolf – on the grounds that Petrov had possessed it unlawfully. On 21 February the court satisfied the claim, and 100 per cent of the shares in Rolf were converted into the income of the state.

In March, Rolf employees were introduced to the new owner – Umar Kremlev, one of the leading players on the Russian bookmaker market, associated with the head of the Security Service of the President, Alexey Rubezhny. The Rolf case became yet another step in the direction of emergency legislation and redistribution of private property at the Kremlin’s pleasure.

The three key legal grounds for the seizure of private property in 2024 were:

- Unlawful enrichment. The most popular pretext for the seizure of assets in 2024 became unlawful possession or enrichment. The state obtained assets in a sum of no less than 632 billion roubles ($7.8 billion) on these grounds. Courts took an average of 4.5 months to examine such claims, but in individual cases the trial was much speedier. For example, the nationalisation of the Chelyabinsk Electrometallurgical Combine (ChEMK) took less than a month, while the biggest case of the year – the seizure of the assets of ‘crab king’ Oleg Kan – was completed in two months.

- Corruption. Nationalisation on the grounds of violation of anti-corruption legislation or fraud took place more quickly than standard ‘de-privatisation’ trials – in 3.5 months on average. The value of the seized assets in this category comprised no less than 185 billion roubles ($2.3 billion).

- Extremism. The procedure for processing claims against owners recognised as ‘extremists’ (mostly Ukrainian entrepreneurs) was even quicker. The average period for consideration of such cases comprised one month, and a minimum of 40 billion roubles ($500 million) worth of property was transferred into the budget.

Setting aside the details, the Prosecutor General’s Office’s wording may appear legally sound. In practice, however, once a political order targeting a specific asset or businessman is received from above, the prosecutor’s office begins searching for suitable grounds for nationalisation. If an asset had at one time been privatised (the statute of limitations and changes of ownership are of no relevance), it is possible to declare that the privatisation had taken place with violations, and seize the asset on these grounds.

If the owner of the asset had been a deputy of any level for some period of time (as were the majority of businessmen until recently), such a situation falls under unlawful combining of a deputy’s post with commercial activity. If neither option applies, the fact that the owner holds a second citizenship or has registered a company linked to the asset in a foreign jurisdiction can serve as a useful basis for action. The extremely short turnaround times for case reviews indicate that the courts are merely rubber-stamping decisions based on the claims submitted by the Prosecutor General’s Office.

The logic of the 2024 requisitions changed in comparison with previous years. Initially, the emphasis had been placed on supporting the work of the military-industrial complex (MIC) and on geostrategic considerations associated with infrastructure and logistics. Here is how prosecutor general Krasnov described this in March 2024: ‘15 strategic enterprises just in the sphere of the MIC alone with an overall value in excess of 333 billion roubles [$4.1 billion] that had unlawfully left the possession of the Russian Federation, and in some cases had ended up under foreign control, have been returned in judicial procedure into its ownership, I will underscore, since the year 2023.’ In the words of the prosecutor general, residents of unfriendly states, having acquired enterprises of the MIC in contravention of prohibitions, were working towards destroying these enterprises and harming Russia’s defence capabilities.

In the current situation there are fewer and fewer lofty state considerations, while the appetite of the state and of specific individuals for private property is growing. It is not by chance that minister of finance Anton Siluanov, appearing at the St Petersburg Forum 2024, discussed the privatisation of nationalised assets and – over the long term – a hundred-fold increase in incomes from this process. The treasury benefits from the revenue, while ‘overachievers’ – such as Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov or the president’s chief bodyguard Dmitry Rubezhny – acquire the assets of businessmen deemed disloyal or insufficiently loyal.

Score: 2 – substantial development

- The cohort from whom property is being requisitioned has expanded – now including insufficiently ‘loyal’ Russians, especially those residing abroad.

- The range of targeted assets has also grown – moving beyond previously privatised property to encompass assets of military-industrial or strategic significance.

- The wave of property seizures in 2024 is reminiscent of the end of the Bolsheviks’ New Economic Policy (NEP) – a period of partial market liberalisation in the 1920s that was ultimately abandoned in favour of strict state control. Henceforth the state is declaring rights to any property of citizens found within the ambit of its reach.

Political elite renewal

Elite renewal is the regime’s Achilles’ heel. The system is getting older, together with Putin, and is experiencing ever more serious problems with top-level managers who are part of the president’s nomenklatura. The problem is not being addressed systemically, but through ad hoc fixes. This approach both undermines the effectiveness of the personnel and heightens the risk of a staffing crisis should Putin’s ageing associates retire en masse.

The May–June package of new top-level appointments, the largest throughout the time of the war, includes some 20 people. It is worth underscoring that this was specifically a package (a systemic, comprehensive decision), which included – besides reshufflings in the government and the presidential administration – long-overdue appointments of the chairman of the Accounts Chamber and the head of the Federal Customs Service (FCS).

How can it be explained that even as the elites’ dependence on Putin has increased, some important appointments are not being made for months, if not years? The ageing tsar Putin is not capable of personally maintaining a constant balance of forces within the elites and will not risk upsetting it even for a time. Appointment via a balanced package makes it possible to avoid this risk.

The actual reshuffles during the time of the war have become more compact, economical, and in large part reactive. The Kremlin is not thinking about the career trajectory of the appointees but, in military style, redeploys personnel to wherever they can have a greater effect for the system as a whole. The old deck is being reshuffled; there are practically no new people making their way into the pinnacle of the elite; that said, neither is there an outflow of personnel (if targeted repressions are not counted). The number of age-related retirements has diminished.

Those screws in the administrative machine that have turned out to be situationally redundant are transferred from ‘technocrat managers’ to ‘political technologists’. (Putin’s nomenklatura bureaucracy consists of five cohorts: siloviki, state decision-makers (technocrats), the business bloc – state and private business, political technologists, and regional politicians.)

In 2024, vice-premier Viktoria Abramchenko, minister of energy Nikolay Shulginov, and minister of sport Oleg Matytsin all lost their posts in the government – and leadership positions in the State Duma were immediately freed up for them.

Several 2024 shifts substantively altered the design of the system. These were the radical replacement of the leadership of the Ministry of Defence, including the replacement of minister Sergey Shoigu with Andrey Belousov; the replacement of Nikolai Patrushev in favour of Shoigu in the post of secretary of the Security Council; the appointment of Alexey Dyumin as aide to the president and secretary of the State Council; the replacement of the leadership of ‘United Russia’ that began with the departure of secretary of the General Council Andrey Turchak.

Some shifts seem to have a more simulated character. For example, the swapping of Kaliningrad governor Anton Alikhanov, who until 2015 had been director of a department in the Ministry of Industry and Trade, with deputy minister of industry and trade Alexey Besprozvannykh. Alikhanov returned to Moscow as minister, while Besprozvannykh went off to Kaliningrad as governor.

The design of the system is shaped not only by radical reshuffles, but also – albeit less noticeably – by the absence of change where it is clearly needed, given the age and physical frailty of certain figures in key positions. This applies first and foremost to the law-enforcement and judicial system.

The oldest of the old-timers in the system until recent times was the chairman of the Supreme Court, 80-year-old Vyacheslav Lebedev, who had been appointed a staggering 35 years ago, under Mikhail Gorbachev. Lebedev died in February 2024 while still in position.

His colleague, chairman of the Constitutional Court Valery Zorkin, is 82. He first took up his post under Yeltsin (he held it in 1991–1993), then was appointed a second time in 2003, and has been heading the court to this day.

Sergey Lavrov is 75; he became minister of foreign affairs 21 years ago. Yuri Ushakov is 78, and has held the post of assistant to the president for foreign policy for 13 years. Alexander Bortnikov is 73, and has been running the FSB for 17 years; Alexander Bastrykin is 71, and has headed the Investigative Committee for 18 years. Yuri Chikhanchin is 73, and has been heading the Federal Service for Financial Monitoring for 17 years.

On the one hand, for 72-year-old Putin – who has held the presidency for 21 years, with only a nominal interruption during the tandem with Dmitry Medvedev – it is more comfortable to rely on long-serving, trusted personnel. At the same time, placing ageing managers at the helm of potentially powerful institutions reduces the risk that these bodies might begin to act independently.

Putin’s system of ‘overseers’ has become widespread. It involves appointing individuals personally loyal to him to senior – often strategically important – positions within institutions, regardless of their direct connection to the organisation. The goal of such appointments is not to reform the institution, but to ensure control and a direct line of communication with the Kremlin.

Among the overseers are head of the Federal Customs Service (FCS) Valery Pikalev, from among Putin’s adjutants; the new chairwoman of the Supreme Court – Putin’s classmate from Leningrad University Irina Podnosova; the president’s first cousin once removed Anna Tsivileva, appointed state secretary of the Ministry of Defence. New minister of defence Belousov – not a military person, appointed from the outside, loyal to Putin and under his personal control – can be included among the overseers as well.

An overseer placed at the head of a corporation brings it into a state of semi-paralysis – at least until they familiarise themselves with the organisation and gain control of its levers of management. Thanks to the reshufflings of 2024, many key structures found themselves in just such a state: the Security Council, the State Council, the Ministry of defence, customs, the Supreme Court. Nothing of the kind had been observed before.

Problems with the personnel pool have worsened significantly as Putin and his close associates have grown older. Hence the advancement to high posts of members of Putin’s ‘extended family’:

- Adjutants and bodyguards: aide to the president and secretary of the State Council Alexey Dyumin and director of the FCS Valery Pikalev in addition to minister for emergency situations Aleksandr Kurenkov and personnel manager of the presidential administration Dmitry Mironov.

- Relatives: Anna Tsivileva and Sergey Tsivilev.

- Children of friends and associates: Dmitry Patrushev, Boris Kovalchuk, Pavel Fradkov.

- Friends of children: Kirill Dmitriev.

- University classmates: Irina Podnosova.

The ‘extended family’ accounted for over 40 per cent of the high appointments in 2024.

While the system has clearly exhausted its resources at the very top – the level of officials personally appointed by Putin – it includes, starting from the next tier down, a built-in mechanism for renewing the personnel base. The model for this rejuvenation can be called ‘Mishustinist-Kiriyenkovist’, from the surnames of the prime minister and the top man in charge of domestic policy. In this model, there is a procedure for the selection and training of personnel that contains elements of meritocracy. The training projects and initiatives include the ‘digital spetsnaz’ (cyber special forces) and Kiriyenko’s programmes ‘Leaders of Russia’, ‘School of Governors’, ‘School of Mayors’, ‘Time of Heroes’, and others.

The call to integrate ‘war heroes’ into the elite turned out to be largely symbolic. In practice, at the federal level, the initiative has functioned more as a training programme for existing elites – similar to the ‘School of Governors’. In the regions, the same programme serves to prepare returning soldiers for demobilisation.

Active rotation is under way at the deputy minister level – part of Mishustin’s nomenklatura. In four ministries where the ministers were replaced (Industry, Transport, Energy, and Agriculture), nine out of 35 deputy ministers – roughly a quarter – have been newly appointed since May 2024. A similar proportion is seen in the Ministry of Economic Development, where the minister remained unchanged: three of the 11 deputy ministers are new.

At the regional level, a rotation has taken place in the governors’ corps: four governors have become ministers, one an assistant to the president, and three were removed from their posts. This amounted to a renewal of nine per cent of the entire gubernatorial corps.

This was the first time that a systemic revitalisation of the federal elite had occurred by way of simultaneously bringing in several officials who had done their ‘internship’ in the regions. Notably, four of the five governors called up to the federal level in 2024 had had experience working in the federal government or the State Duma prior to having been sent into the regions in 2016–2019. Four of the governors had had experience working in the presidium of the State Council, where they headed commissions on matters related to their new jobs. Their current appointment to the government looks systemic and prepared in advance. In essence, this is the first graduating class of the ‘school of ministers’.

For an analysis of the upper echelon of Putin’s elite (see Fig. 6), we propose a benchmark group of profiles consisting of:

- Permanent members of the Security Council (13 persons).

- The leadership of the presidential administration (18).

- Regular participants in Putin’s meetings with members of the government (14).

- Putin’s ‘security cabinet’ (12).

- The federal part of the State Council presidium (6).

- Members of the presidium of the Council for Strategic Development and National Projects (19).

- Members of the presidium of the government of the Russian Federation (21).

- Those most directly responsible for carrying out the president’s assignments in 2024 (21).

Taking into account numerous overlaps, the database includes a total of 83 individuals. In addition, ten more were added – senior figures from the media sector and regional leadership.

Fig. 6. Distribution of the top level of Putin’s elite by age and length of service

The numerically largest groups turned out to be political technologists (30) and state decision-makers (26). Next, with a large gap, come siloviki (12) and regional politicians (10); the smallest cohort are businessmen (5).

The average age by groups fluctuates in the 59–66 range; moreover, the youngest are the civil servants (59) and the oldest are the siloviki (65). Average length of service at one’s current position is eight-nine years for political technologists, siloviki, and regionals; the shortest is among civil servants (five years), and the longest is in business (14 years). The spread broken down by length of service and age is considerably large: every sixth official is aged 70 or more, every fifth is under 50. Overall, a direct dependence can be observed between age and length of service.

The upper tier of Putin’s nomenklatura elite appears ageing and firmly entrenched in its positions. While this provides stability for now, it also carries the risk of future destabilisation as key figures in the regime near the end of their political careers.

Score: 2 – substantial development

- The system is losing momentum due to ongoing reshuffles and the natural ageing of Putin’s inner circle – a dynamic reminiscent of late Brezhnev-era stagnation.

- While mass appointments have accompanied the start of the new presidential term, the regime has retained its inefficient practice of promoting long-time loyalists. In contrast, a more functional mechanism for renewing personnel operates one level below, where appointments carry little political weight.

- Among the new trends that emerged in 2024, two are particularly noteworthy:

- Rapid expansion of the overseer model via Putin’s ‘extended family’.

- The first graduates of the ‘school of ministers’ – federal officials who completed an ‘internship’ in the regions and the State Council.

Dismantling the patronage and institutional pyramids

Putin’s arrival at the post of president in 2000 marked the beginning of centralisation 1.0 – the dismantling of the quasi-federation of regions. Built in its place was a quasi-federation of institutions, which the Kremlin began to systematically dismantle in 2014. Centralisation 2.0 had begun, in the form of deinstitutionalisation. The abrupt replacement of the entire management and administration leadership at the Ministry of Defence in 2024 became one of the radical examples of this second centralisation.

There are two directions for dismantling the pyramids of power:

- Radical replacement of the top ranks – ‘decapitation’, for example, the firing of Sergey Shoigu from the Ministry of Defence in 2024 or Anatoly Chubais from Rosnano in 2020.

- A gradual weakening of the upper echelons of power is taking place through natural attrition – ageing and behind-the-scenes manoeuvring. In the Federation Council, the tandem of speaker Valentina Matviyenko and her first deputy, seen as a successor-in-waiting, remains in place. A similar dynamic was visible in the Supreme Court, where Irina Podnosova began to assert herself during the later years of the ageing chairman, Vyacheslav Lebedev, between 2020 and 2024.

Since 2014, the top tiers of many institutional pyramids have been replaced – the Administrative Directorate of the President (2014), Russian Railways (2015), the Federal Protective Service (2016), Rosnano (2020), and others. None, apart from Putin’s own (the presidential administration and the administrative directorate), has preserved any autonomy after these changes: regardless of what form of independence they previously enjoyed, all have been fully integrated into the unitary Kremlin system.

Replaced in 2024, besides the leadership of the Ministry of Defence, was the leadership of the Supreme Court, the Federal Customs Service, the Accounts Chamber, and five ministries – subdivisions of the governmental ‘corporation’. In most of the cases (besides the Ministry of Agriculture), the new head came from outside. A special case is the Supreme Court. Its new chairwoman Irina Podnosova was brought in from outside straight to the post of deputy to the chairman Vyacheslav Lebedev back in 2020, while the previous candidate, deputy chairman Oleg Sviridenko, was transferred from the Supreme Court to the Ministry of Justice.

Most of the time, appointing an external figure to head an institution signals that the formation of new institutional pyramids is unlikely in the foreseeable future. The ability of an institution to act in a consolidated manner as a political actor decreases, while control over the institution on the part of the Kremlin increases. A reduction in the institution’s efficiency also occurs, at least for a time. The Ministry for Emergency Situations can serve as an illustration of the latter: it has had three different chiefs over the past six years, and yet is proving incapable of delivering the required level of efficiency.

The sweeping replacement of the Ministry of Defence leadership in the midst of the war – at a time when the situation on the front lines had begun to stabilise in Russia’s favour – should be understood as a sign that military operations are expected to continue for an extended period.